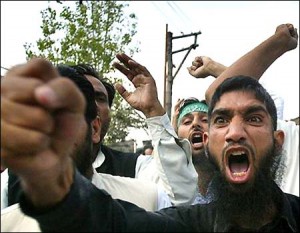

In the Times today (Tuesday) there is a leader trying to respond to the news of two young men from Britain killed in Syria and Kenya respectively in the cause of radical Islam. The crux of the article appears at the end when the writer appeals to Muslim leaders to face up to ISIS recruiters with vigour, stating what is and what is not acceptable in Islam. The leader notes that only one national leader, Egypt’s President Sisi is calling for a ‘religious revolution’ to counter the ISIS ideology. This appeal is somewhat vitiated by the fact that thousands of suspected Islamists are being jailed by his regime, only to encourage the recruiting of thousands more to the extremist cause.

In the Times today (Tuesday) there is a leader trying to respond to the news of two young men from Britain killed in Syria and Kenya respectively in the cause of radical Islam. The crux of the article appears at the end when the writer appeals to Muslim leaders to face up to ISIS recruiters with vigour, stating what is and what is not acceptable in Islam. The leader notes that only one national leader, Egypt’s President Sisi is calling for a ‘religious revolution’ to counter the ISIS ideology. This appeal is somewhat vitiated by the fact that thousands of suspected Islamists are being jailed by his regime, only to encourage the recruiting of thousands more to the extremist cause.

The issue for Muslims is ultimately a theological one. The question for every Muslim is to face up to what they believe about truth. Does their grasp of truth require them to battle against and kill other people who differ from them in the way that truth is expressed? Is the only way that devotion to a truth can be expressed to be through militancy? Of course we recognise that differences between Sunni and Shia have become over the centuries a tribal and nationalist division, but the battles between them are still articulated in a theological language. If there were another narrative available which did not stress the theological gap between Shia and Sunni, then no doubt a political compromise might be far easier to achieve in the nations of the Middle East. Instead we have the online hate preachers corrupting young minds with their endless propaganda. They will be talking about devotion to God and the costly sacrifice that is required of all true devotees. This kind of language will be heady stuff to a young, possibly unemployed, young man. He is being offered a focus for an otherwise chaotic life, something which will give it meaning and direction.

Christianity itself has not been free of the rhetoric of extremism and violence. The preaching that preceded the Crusades in the 11th century dwelt on the importance of regaining Christian lands and killing infidels in return for divine forgiveness. It also gave the younger sons of the nobility, those who would not inherit land from their families, a chance to make a fortune from the plunder that might come their way. Historians will tell us that people went on crusades for a multitude of motives, some possibly honourable, many not. Nevertheless whatever the true reasons, the official script was that Christianity was superior to all other religions and this ideological dominance over all its rivals needed to be expressed by military conquest. Both Crusaders and members of ISIS are bound together by a conviction that they are in possession of an ultimate religious truth. Because, in each case, their faith is the best and purest form of religion, their rivals must give way to this inbuilt superiority. The fanaticism of the beliefs of the ISIS is such that they have convinced themselves that they have the right to kill, not only infidels who are not Muslims but also their fellow Muslims who do not follow their particular interpretation of the Koran.

At the heart of fanaticism, whether Muslim or Christian, is a belief that the believer possess the truth because it is contained in a holy book. A book, through the fact that it has written content, appears to have an objectivity about it, making it superior to other ways of mediating religious truth. It is obvious that an experience, orally transmitted, will change over time. A written document, on the other hand, will not change and will thus seem to preserve a fixed meaning. Since the Reformation in West, many of us have got used to the idea that the words of Scripture do not in fact have a single interpretation and the proliferation of denominations and churches bear witness to this fact. But something of the mystique of words in a book, especially the Bible or the Koran, as having a supreme authority, has remained part of the thinking of many people today. This respect for a Holy Book is such, that, to this day, some people seem reluctant to read it for themselves but leave it to the pastor/minister/iman to read and interpret it for them.

Fundamentalism, whether in Islam or Christianity, maintains in each case a highly dependent relationship with a written text. With a devotion to words that was more understandable in an illiterate society, it maintains the fantasy that the written text is a gateway to an objective expression of truth. The particular version of truth within the book is so compelling that other people must be forced into agreement. In the case of Islam that force is sometimes expressed in cruel violence. In the case of Christians physical violence is not used because the traditions of our modern democratic societies would not tolerate anyone using force against another to further religious ends. When, however, you listen to extremist groups within Christianity talking about other people who disagree with them, you wonder how close to the surface are murderous and violent thoughts. Every time I hear Christians speaking about demonic possession existing in those they disagree with, I hear the language of violence. The whole obsession with the gay issue on the part of those who campaign against it has the marks of a crusade with all its negative and cruel connotations.

My final comment in this reflection about theology and violence is to suggest that we listen carefully to the rhetoric of Christians to identify the underlying violence in the language that is sometimes used. From the beginning, Christians, like Muslims, have shown themselves capable of being able to be inflamed to the point of violence in the defence of their vision of truth. Every time a Christian wants to trash and discredit another Christian for not agreeing with their vision of truth, they are committing violence. It may not be physical but the intemperate language of Ian Paisley or many other conservative preachers can also be seen to be violent. It has as its aim the destruction of other people and their words and ideas. As I said in my piece on ostracism, people can also be destroyed by silence every bit as effectively as by weapons. It is easy to trot out at this point Jesus’ injunction to love our enemies. But perhaps we should indeed spend time reflecting on this command. Above all, it should make us sensitive to the need never, never to regard people who think differently from ourselves as people to be attacked with words of violence. Difference never justifies violence of any kind.

A quote from Jonathan Sacks which concluded the Times leader: ‘We have little choice but to reexamine the theology that leads to violent conflict…’ That would apply to Christians as well as Muslims.

Yes. There’s a whole field of study in the area of the underlying violence in words. It pays to have that in mind when designing liturgy, too.

There seems to be a big squabble in religion (And its evolution) over the nature of God.

Will this be settled in the next generation? I doubt it.

Personal interpretation with all its bias and absolutism seems to rule the subject.

Humans are such a slippery beings. Whether they are fundamentalist, liberal, modernist, the tendency is for them to worship his or her conclusions. Stephen sees God as unconditional love, I hope in that God.

Deeply sad and getting more so,

Chris Pitts

It is sad. But I agree with Stephen. The real God is indeed unconditional love. Everything else has to be set beside that to see if it matches up.