What has the gospel got to offer victims of abuse? What is ‘good news’ for those whose most urgent problem is not their own sin, but the damage done by someone else’s sin against them?

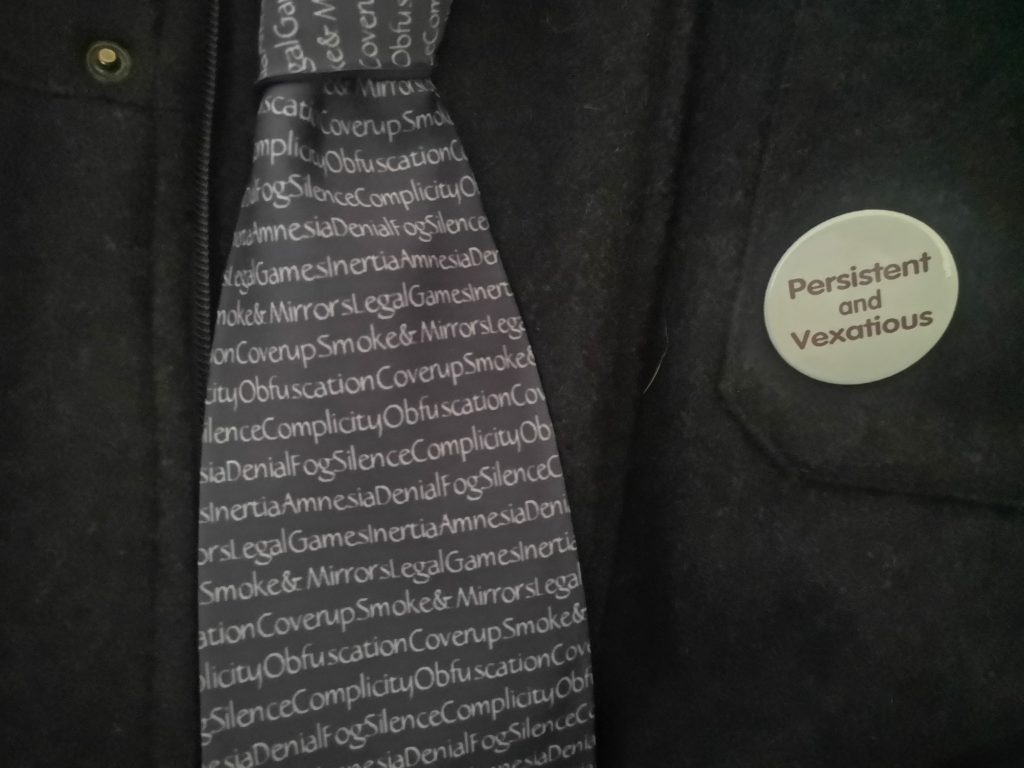

A survivor attending a Common Worship Holy Communion service (and many parishes offer nothing else) might well conclude that Christianity cannot help them. The focus is entirely on sin and forgiveness, and the work of Jesus presented almost solely as saving us from our sins. The theme runs through the service from the penitential material at the beginning to the prayers before the distribution of the consecrated elements, and is sometimes repeated in the post-communion collect.

Undoubtedly salvation from sin is a key theme both in the Bible and in Christianity generally. I would argue, however, that to narrow the gospel down just to forgiveness from sin as the Church is currently doing, is to seriously distort it. I’ll illustrate this by looking at two examples from Common Worship.

The first is the introduction to the confession in Holy Communion Order One: God so loved the world that he gave his only Son Jesus Christ to save us from our sins, to be our advocate in heaven, and to bring us to eternal life.

Contrast it with John 3:16, which it quotes: For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.

Verse 17 continues: Indeed, God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.

The original in John offers relief from the fear of death, with the implication of a new quality of life now, and freedom from condemnation ‘to those who believe’. The invitation to confession more specifically names Jesus’ mission as ‘to save us from our sins’, with ‘to bring us to eternal life’ second, and as a delayed prospect. It also introduces the idea of Jesus as our ‘advocate’ – lawyer – in heaven. The whole mood of the passage has changed from freedom and relief, provided for us by God’s overwhelming love, to apprehension of appearing in the dock in a cosmic courtroom with God as Judge – a daunting prospect, even with Christ as our barrister.

Moreover, rather than approaching our advocate directly, we are supposed to rely on an intermediary – the priest – to dispense absolution. The idea of an intermediary other than Christ is foreign to this passage from John, and scarcely present in the New Testament.

Our second example is the options given for prayer before the distribution of Holy Communion. Both distort the lesson to be gained from the tale of the Syrophoenician widow in Mt. 15 and Mk 7. The point of the story is that God’s grace is so abundant that it’s available to all – ‘even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table’. Even Syrophoenician women are ‘worthy’ to eat the crumbs – how much more so the children of the household! And yet, after confession, absolution, sermon, declaring our faith, exchanging the Peace and all – we are supposed to say we are less worthy than dogs. This is hardly Good News, especially for those downtrodden and lacking confidence.

The virtues of Common Worship are that there is supplementary material, and that it allows freedom to borrow from external liturgical sources, especially during the ante-communion. Few clergy make the most of this freedom, however. The core of the liturgy used in most parishes shows a very limited understanding of the mission of Jesus. Understandably, then, even regular worshippers can assume that Jesus was born and died solely so that our sins can be forgiven.

Contrast this assumption with Jesus’ own declaration of his mission: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.” Luke 4:18-19

There is nothing in this passage about sin. Jesus speaks here of being sent to the poor, the prisoners, the blind, and the oppressed; and he speaks not of forgiving them but of healing them and setting them free.

Likewise, the Sermon on the Mount, the core of Jesus’ teaching, begins with words of blessing for the poor (Luke) or poor in spirit (Matthew); the meek; the persecuted; mourners; and the hungry (Luke; Matthew has ‘those who hunger and thirst for righteousness’). It is clear that Jesus is concerned for those who suffer, whether physically or emotionally, and meeting their needs.

Jesus challenged some people regarding their sin, especially religious leaders. However, he healed and delivered many to whom he does not seem to have mentioned sin. He resisted the others’ attempts to reduce everything to a question of sin and guilt, and frequently criticised religious leaders for laying heavy burdens on ‘ordinary’ people and the poor.

The concept of salvation itself has been narrowed to a focus on the forgiveness of sin. The principal Hebrew term for salvation, (yesa’) means ‘to make room for’ or ‘to bring into a spacious environment’. It connotes freedom from things which restrict or limit. It is the word from which the name ‘Jesus’ is derived.The Greek term sozein originally meant ‘to deliver from danger’ or ‘to make safe’. In both Hebrew and Greek the word used for ‘salvation’ meant safety, deliverance from danger, and freedom from restriction.

Sin is one of the things which threatens and restricts us, and saving us from sin was certainly part of Jesus’ purpose. But other things also threaten and restrict us, and particularly the survivor of sexual abuse: fear, shame, despair, self-loathing, poor decision-making. Children and young people who are abused are not given the right conditions for growth, and their development into psychologically healthy adults is restricted. A true sense of self must be given space to develop. For them maturing into Christ will mean not sacrificing self, as much traditional teaching demands, but learning who they are and what they want. Psychological limitations such as the inability to set boundaries, trust one’s own perceptions, or seek to have one’s needs met are properly a part of the work of salvation. As Kathleen Fischer commented, ‘the movement of God in our lives emerges as we come to know our deepest selves’ (Women at the Well: Feminist Perspectives on Spiritual Direction, p. 114)

We seldom see this wider picture of salvation reflected in our liturgy, which is the ‘shop window’ of our Church and both reflects and moulds our theology and spirituality. The seasonal material, including collects and Bible readings, does draw on themes such as events in the life of Jesus and the doctrine of the Trinity, but these are still set within a framework which is almost exclusively about the sins and need for forgiveness of the worshipper.

Imagine the effect of this skewed emphasis on those who come to church hurting physically and emotionally, frightened, with no sense of self respect, and never having had a chance to discover who they really are. They are faced almost immediately with a prayer saying God knows all our secrets, and are then required to search their own hearts and minds for the things they have done wrong. For an individual in such a condition the confession can be a further abasement. Imagine if, instead, they were greeted with: ‘Jesus said, the Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor…to let the oppressed go free…’, and the rest of the liturgy took its theme from that. It would be liberating not only for sexual abuse survivors, but for many others: the poor, the depressed, the sick, and those struggling with all kinds of problems.

This article is an excerpt from the chapter of the same title in Letters to a Broken Church.