The Internet is a great provider of information. Of course, there are to be found in it lies, rumours and falsehoods. We trust, however, that a reasonably discerning person can detect ‘fake news’ and not fall into the trap of repeating unsubstantiated information. But there is another sort of truth that can be found from scrutinising the net. An individual can pick up information from a variety of separate sources but be able to suggest how these fragments of information are connected. None of the fragments of information I tell below stand as complete stories. However, when they are linked together, they seem to tell a complete story, one that does little credit to the Church of England or its breakaway sections represented by GAFCON and AMiE.

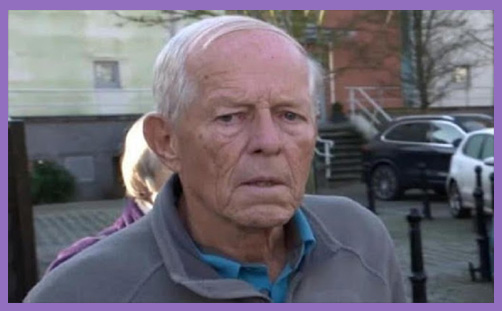

The first section is a statement by Bishop Andy Lines, the clergyman appointed by the breakaway Anglican American group ACNA to act as a missionary bishop for Europe. He is also closely linked to AMiE the group that brings together parishes that have opted out of the Anglican Communion. He recently announced to this group that he was withdrawing from active ministry for a few months, having been a victim of ‘spiritual manipulation’. This highly unusual and unexpected announcement has obviously led to speculation. Who was doing the abusing? Who, in short, had the authority over this powerful figure in the Anglican breakaway world to be able to be able to create what appears to be a major crisis for a respected figure? The only clue we get is from the description of the abuser. Andy speaks of a ‘betrayal of trust by a mentor’. No names are given but looking at Andy’s formation and links over many years with Emmanuel Church Wimbledon, we have to suggest that the Vicar, Jonathan Fletcher, a close friend and teacher, fills the description. It was also Jonathan that was present at some kind of ceremony of commissioning Andy in Emmanuel following a consecration service in the States. Jonathan had been Vicar of Emmanuel Church for 30 years. He was thus a major figure in Andy’s life and in conservative Anglicanism generally. Everyone in that world seems to know him or comes in some way into his orbit of his influence. This Wimbledon church seems to be a kind of central hub for the entire conservative evangelical network within Anglicanism. It is still a centre of great importance, along with such centres as St Helen’s Bishopsgate and St Ebbes in Oxford.

A second story that has broken in the past few days also concerns Jonathan Fletcher. He was named by the Daily Telegraph in a story that has all the signs of having been pored over extensively by lawyers. The story revealed that in 2017 the Diocese of Southwark had removed the Permission to Officiate from Jonathan on the grounds of unspecified abuse against vulnerable adults. The Telegraph story provoked a reply on the website of Emmanuel to apologise and offer help to anyone who had been affected by the story. Clearly, although the offences may have fallen short of being criminal, there was in the minds of members of his own church a case to answer. It is worth pointing out that although the church and other senior leaders have known about the allegations for two years, it is only now that they are offering support to those who may have been affected.

A third story or anecdote, no doubt provoked by the Telegraph story, was the publication of a photo showing a programme from one of the Iwerne public school summer camps dating back to 1982. This showed John Smyth as a speaker on the same day as Jonathan Fletcher. These two men obviously knew each other well. Clearly also the networks of people who supported the Iwerne camps and their work were well known in Emmanuel circles. It is hard or impossible to imagine that Jonathan Fletcher was left in the dark about John Smyth’s crimes and the reasons for his sudden departure for Africa. This Iwerne/Emmanuel nexus would have had enormous power and influence. We should not underestimate how much power seems to have accrued personally to Jonathan Fletcher as the man in charge of Emmanuel and a key player in Iwerne circles. Any suggestion of wrongdoing by this superstar of the evangelical universe is highly embarrassing, not to say highly destructive, to the wider evangelical world. Jonathan’s power reached out not only to those who were personally caught up by his charisma but he had institutional power, wielded through his participation in committees and other structures of influence. John Smyth’s crimes have already cast one heavy pall over the legacy of Iwerne and the hundreds who passed their formative years within its orbit. Silence on the part of those who knew about Smyth’s crimes has made the eventual effect of discovery far more serious and painful. A similar silence protecting Jonathan over the same period of years has also been allowed to exist. Whatever Jonathan is or is not guilty of, the silence maintained by many who knew allegations against him has made a bad situation far worse.

A final fragment of this complex story is the suggestion online that Jonathan Fletcher has been a member since 1983 of the exclusive dining club, Nobody’s Friends. This club which emerged into public awareness during the IICSA hearings in March last year has a membership group of 60, all elected by the club itself. Each of the members is chosen from either the church, politics or one of the other distinguished professions. Jonathan’s place among this elite group is no doubt in part the result of being born into a family of eminent politicians, his father having served a member of Harold Wilson’s cabinet. But apart from this family background, someone in the church must have seen him to be an important up and coming church person. Thus, in his 40s, he was honoured to sit among Deans, Bishops, and the like, not to mention the crème de la crème of the political establishment. Perhaps as importantly there was another group represented in the club, public-school headmasters, the supporters of Iwerne camps.

Mention of this dining club, Nobody’s Friends, links us back to the establishment network that played an important part in the Peter Ball story. We catch a glimpse of a well-connected group of people who were able to pull many strings, partly because of whom they knew. Jonathan Fletcher was right there in the middle of it all. In other words, like Peter Ball, he knew and was known by enormous numbers of movers and shakers in British society. Also, as with Peter Ball, if the accusations of ‘spiritual manipulation’ are true, then many people would have been affected. Peter Ball’s world was the high church networks so well represented in the Chichester diocese. Jonathan Fletcher’s world is the evangelical nexus represented by the conservative parishes of REFORM. Here we find considerable wealth, privilege and power. Jonathan’s potential capacity to do good and provide a positive influence was enormous. Equally his ability to create harm was extensive. The story, as we have it, is in fragments but we are hinting that the joined-up version we have now points sadly to the latter scenario. As with Peter Ball’s story, the discrediting of an admired hero in an institution goes far further than simply among those who knew the hero directly. It spreads out to many others who expected the highest standards of their leaders.

It is unfortunate that twice in one week we are reflecting on the influence of single individuals on vast numbers of other Christians in our church. Any attempt to deny the influence of these two prominent Christians on others would be a distortion of history and would also dishonour the pain of betrayal that abused victims may often feel. If Jonathan Fletcher is indeed shown to be guilty of spiritual manipulation, then we can be sure that the number of his victims is large. Also, whenever a sense of betrayal is found within an institution, it has a tendency to infect the whole. The healthy mutual interdependence that would have operated so well in evangelical fellowships would be weakened if a miasma of suspicion and fear starts to flow through these networks. That situation is indeed what we seem to be beginning to witness. Failures of trust have no good endings. In the same way we need rebuilding of integrity and openness and an end to the networks of secrecy and privilege which flow through this story. It is a story of four fragments but when drawn together it becomes a story of power abuse, dishonesty and harm. Directly or indirectly this story affects us all.