Recent rumblings within the UCCF (Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship) might never have attracted much attention but for the clumsy efforts to avoid full disclosure and transparency. Back in December 2022, some problems in the organisation arose and resulted in the suspension of two very senior officials within the group, Richard Cunningham and Tim Rudge. An internal enquiry on behalf of the Trustees, that was started in the early part of this year to investigate the issues behind these suspensions, has taken a significant amount of time to complete. The report containing the results of this inquiry by Hilary Winstone KC was apparently delivered to the Trustees in June. Nothing in this report was shared with the wider public until now. What we have now in statements from the Trustee body is a rather vague statement which suggests that there have been some issues to be resolved over the contracts and terms of service for the charity volunteers and employees. The recruitment and support of dozens of young people who work for UCCF is a major part of the charity’s activity. Meanwhile, the two suspended directors have apparently been found innocent of whatever accusation had led to their suspension, though it is not clear what required the suspensions in the first place. Also, we heard another fact at the beginning of this month which was the resignation of almost half the trustees from the UCCF Trustee Board. This included the Chairman, Chris Wilmott. Only the vaguest of reasons have been given for this event. Clearly something is going on within the organisation beyond a dispute about employment law and the practices currently used to recruit and manage those working for UCCF.

In trying to understand what might be going on in a religious organisation which many people may not have even heard of, we have first to revisit briefly the 1920s and the founding of its predecessor, IVF (Inter-Varsity Fellowship). it was realised then by evangelical church leaders across the denominations that students at university, brought up in traditionally conservative home churches, needed spiritual, social and intellectual support in order to grow in their faith. The name-change to UCCF came about in the 1970s when this work among students at university was extended to cover colleges of higher education. Christian unions attached to UCCF are currently found in almost every higher educational establishment across Britain as well as in some schools. UCCF provides a network of staff members to support these Christian Unions with training and organisational support. Almost all of these supporting staff are young and recent graduates. They will have played an active role in their local Christian union while still undergraduates. These junior members of staff are there to help and encourage new generations of students to be active in the task of evangelism. This is done through Bible study and prayer groups, as well as more focussed evangelistic events.

In making observations about the work of UCCF, I have the possible advantage of not knowing anyone who is currently part of the organisation. All my comments are based on information freely available on the internet, especially the UCCF website. After studying this site, especially the potted biographies of a few of its workers and volunteers, I found myself comparing what I was reading with an institution which acts in the manner of a military organisation. The central duty and priority for every member of this Christian army of student members was to be a follower of Christ and share freely this witness with one’s fellow students. When not doing the work of sharing Christ with non-Christian friends, the CU requires all its members to engage with frequent attendance at prayer meetings and Bible studies. In short, membership of a CU can be a virtually full-time occupation for both staff and ordinary members. There would be little time for other activities apart from university studies. The ordinary members in the structure could be likened to private soldiers in an army, while the volunteer Relay Workers are a NCO class. Relay Workers are those who have volunteered for a ten-month period to work with the students. Above these Relay Workers were staff members who can be considered to be acting in a junior officer rank. They are expected to stay between three and five years working full-time with perhaps a cluster of CUs. While Relay workers were expected to be entirely self-supporting for a single academic year, the staff members did receive some pay from a central fund. The reality of these arrangements has been opened up in a recent Youtube video. A former staff member spoke of his difficulties rising a third of his salary through fund-raising activities. One imagines that many staff members find themselves subsidised by their own families. All of the viewed sample of 120 or so members of staff that are shown on the website were inviting (begging?) the online visitor to help support them with a financial contribution. Such a system of worker remuneration is at the very least eccentric and questionably legal. It is not difficult to imagine that someone in UCCF has raised their concern about the exploitative culture of employing staff in this way. It may be these strange patterns of employment have resulted in an evident unhappiness in UCCF and the suspension of the two senior directors. My observations are of course speculations but there must be other people who regard the employment culture of UCCF as not fulfilling best practice or working for the best interests of their employees. Another facet of this employment strategy which raises concerns, is that this way of employing staff is exploitative of youthful idealism. Working for UCCF does not offer a secure career path, even if some go on to pursue other careers in Christian leadership. Once again employment law apparently does not look kindly on a system of compulsory redundancy after working for three to five years for the same employer.

My description of the employment practices of UCCF as exploitative might be considered an understating of the issue in the organisation. Taking a cohort of vulnerable young people fired up with enthusiasm for God but with little experience of the world of work, and then expecting them to effectively beg part of their salary from relatives and supporters is an act of questionable honesty. Some might even describe it as something close to slavery. Clearly this culture of using young people to work for less than the going rate is one that is bound to meet a legal or moral challenge at some point. I have no idea whether the suspensions of directors and resignation of trustees has anything to do with the employment regime or not. Clearly there needs to be a proper examination of employment practices at UCCF. This may already have begun.

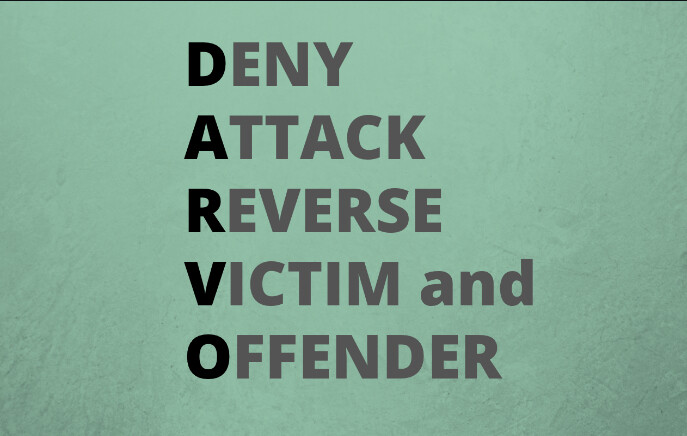

Readers of this blog know about the considerable impact of charismatic styles of Christianity among students and young people. The UCCF emerges from a different ‘tribe’ of evangelical teaching and largely sets itself apart from the charismatic style of HTB and Soul Survivor. The same non-charismatic and quasi-military culture pertaining to UCCF was also found in the Iwerne camps. Iwerne wanted to capture the nation’s leaders by focusing on the ‘best’ public schools. UCCF is impelled by a similar desire to reach the educated student population of Britain with the claims of Christ. In practice, evangelical institutions or large parishes will tend to identify with one style and culture or the other. Most large and ‘approved’ evangelical churches in our university cities, which support CU, tend to identify with the non-charismatic strand. While I have some sympathy for the charismatic expression of evangelicalism, I find UCCF and Iwerne inspired churches decidedly old-fashioned and rigorist. This is especially indicated in their theological statements. The UCCF statement of belief, which consists of eleven propositions, could have been lifted straight out of a 19th century textbook of dogmatic Protestant teaching. From memory it remains identical to the IVF propositions set out 60 years ago when I was an undergraduate myself. Is it a matter of pride that the same unchanging words are thought to be adequate to convey a statement of truth and belief? The attempt to place God in a narrow straitjacket of words always seems a futile task. Even within the New Testament itself we see the language used to describe God changing and evolving. The writer of Mark’s gospel and that of John would not have found it easy to communicate with one another. How is the word ‘infallible’ a helpful one when try to embrace the different cultures of truth within the Old and New Testaments? It takes imagination beyond words to see the harmony between the differing cultures within Scripture. Understanding truth, as having to be expressed in a precise formula of words, is not helpful for an emerging youthful faith. One thing that all members of Christian Unions have In common is their youth. It is, to say the least, unseemly to restrict the desire to use one’s imagination to explore the reality of God and define it in a fixed code of words which are held to be beyond discussion or imaginative interpretation. It is also abusive and cruel to suggest that any deviation from the eleven propositions provided by UCCF is to place oneself on the path to apostasy or even eternal damnation. Any social and emotional pressure applied on this vulnerable group within society, our student population, should be a concern those who make the laws of this country as well as all those who minister to their spiritual and emotional welfare. It is a constant problem to those who seek to serve to minister to students who may find themselves deviating from the thinking of their Christian Unions.

Coincidentally, over the weekend I received a plea from an unknown person who is desperate to receive support from someone who can help her move away psychologically and emotionally from the damaging authoritarianism and ostracism of a Christian congregation. I am unable to suggest any help but perhaps my readers may know of a support network of this kind. It is much needed. Perhaps the tensions and the divisions that are possibly evident today in UCCF may be a prelude to a new generosity and inclusive welcome among evangelicals to one another, especially in the world of supporting Christian students. In short, the frozen culture of a century of IVF/UCCF intransigence may be ready to crack open to let in new light and truth.