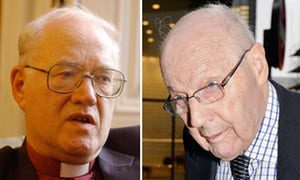

Next week the Church of England is going to have to endure yet another scrutiny at the hands of the Independent Inquiry and the press. The issue at its heart is the criminal sexual abuse by a bishop of a group of young men who believed that they were following a path set out by God. The facts of the case have been thoroughly rehearsed in a court of law so that in many ways the details of Peter Ball’s abusive behaviour do not need to be further discussed. Damage has been done, severe damage, to the lives of those affected but we are left with a need to understand some of the implications for the wider church community. It is these that I want to reflect on in this post. Above all I see the Ball case as a study of the dysfunctions of power in the church. The lessons we can learn from it are relevant today.

Next week the Church of England is going to have to endure yet another scrutiny at the hands of the Independent Inquiry and the press. The issue at its heart is the criminal sexual abuse by a bishop of a group of young men who believed that they were following a path set out by God. The facts of the case have been thoroughly rehearsed in a court of law so that in many ways the details of Peter Ball’s abusive behaviour do not need to be further discussed. Damage has been done, severe damage, to the lives of those affected but we are left with a need to understand some of the implications for the wider church community. It is these that I want to reflect on in this post. Above all I see the Ball case as a study of the dysfunctions of power in the church. The lessons we can learn from it are relevant today.

In looking back over the sad case of Peter Ball, we can first reflect on the nature of the power that he personally exercised. As a bishop in the Church of England, he had considerable social power. Social power was enhanced by his going to the right school and university. His social standing and his status as a bishop meant that he was automatically put in a position of trust by everyone who met him. Nobody needed to make a judgement about his personal honesty or character. The Church in its wisdom had selected him as a priest and a bishop. Throughout his long priestly career of service to the Church those in authority had, it might be assumed, watched over his behaviour and conduct. As a bishop, Ball was welcomed into places right across the social spectrum, the homes of ordinary people as well as the dwellings of the highest and the grandest in the land. Episcopal status and social confidence created a standing which was difficult ever to challenge or question.

Social power was not the only kind that Ball possessed. There was an additional power which is common among some bishops and church leaders. This power we can describe as charismatic power. In using this word, I am not hinting at a churchmanship which involves speaking in tongues or gifts of the spirit. I am speaking of charisma in its wider meaning. Ball had charisma and an ability to inspire, charm and encourage others. His presence in any room or gathering was likely to be the dominant one. We sometimes speak about some personalities being larger than life. Ball was one such and no one who met him failed to be affected by the energy of his personality.

Charismatic power in an individual, as we recognise increasingly today, is a double-edged sword. It can be used to build up others; equally it can be deployed to manipulate others when required. Charismatic power and social power when operating together make an individual very difficult to resist. But, in addition to these forms of power, we must add a third, which is institutional power. People naturally defer to those who are in charge within an institution not least because they have the power of patronage. It does not pay to stand up to anyone in a firm who can make or break your career within the institution. Ball, as a bishop in the Church of England, would always have exercised considerable power in the church even before we add the additional social and charismatic strengths which he possessed. The three sources of power that he had, allowed him to float above suspicion or challenge for decades. If there were concerns at any point about his behaviour towards young men, he had the means to quash such rumours or innuendoes fairly quickly.

Next week we are going to hear once more the sad story of how the Church of England was defeated in its attempt to rein in Ball’s power over decades. Reading the Gibb report once more, it is obvious that Ball was adept at manipulating others even after the English justice system had extracted from him a serious admission of guilt in 1993. The simple way to interpret the events that took place in the years between 1992 and 2015, when he was sent to prison, is to see them as a conflict of power systems within the Church. As I read it, the events of Ball’s evasion of justice demonstrate an effective deployment of his personal power against individuals and institutions that were trying to stop his ministry.

A major threat to Ball after his police caution and his resignation from the see of Gloucester in 1993 was the possibility of having his ministry curbed by some form of inhibition from Lambeth Palace and Archbishop George Carey. The avoidance of a public trial in that year had been a close-run thing. This escape from the full force of the law was arguably assisted by the bombarding the Director of Public Prosecutions with 2000 letters of support. Now Ball had to prevent the Church stopping him exercising a ministry among his supporters. These included public-school headmasters and others high up in terms of social position and status. George Carey’s reluctance to take decisive action against Ball may possibly be read as the conflict of two power systems. Although Ball’s institutional power had been weakened, he still retained considerable social power through his links and friendships with members of the Establishment. Many of these were still mesmerised by his charismatic power. Carey seems to have not wanted to be on the wrong side of the power that Ball could still muster to support him, even though as Archbishop, he could be said to have considerable institutional authority. He must have dreaded the problem for Lambeth Palace if even a small fraction of the supporters who had rallied to Ball’s support at the time of the caution had turned their attention on him. Carey, having risen to the top in the church from fairly humble social origins, seems to have been fairly easily intimidated by the disapproval of his social ‘betters’. I am, of course, speculating at this point, but in summary it is a reasonable reading of the available evidence to suggest that Archbishop Carey was simply afraid of the power that Ball could muster against him. The weak responses made by Carey, including the failure to share relevant letters with the authorities, are the actions of someone who is frightened of a power greater than his own.

Social power, institutional power and charismatic power are phenomena to be found in every institution, including the church. It is when they operate without being identified and understood that they can become a real problem. Ball, in possessing all three types of power, could and did become an extremely dangerous individual in the church. There were few checks and balances on his behaviour and the use of his power. Abusing this power was at the heart of his offending. He was also too powerful to challenge, even after his resignation and police caution. Even when the secular authorities caught up with him, the church still seemed not to understand how they had been manipulated by his narcissism and charismatic charm over a long period. What is likely to be revealed next week is a history of gullibility and naivety in the face of a predator who knew how to exercise power effectively for his own ends and fool everyone else in the process.

It is a human thing to elevate another to the priesthood or Bishop, leader or politician. And once elevated and esteemed it takes a lot to remove the mystical cloaks we have adorned our proxy gods. We become blind to their failures.

Let me give an example of my own blindness. As a medical student, a group of us were being shown how to examine a male patient by an eminent doctor. This physician was a favourite of mine. Unlike many of our teachers he was neither a bully nor a user of humiliation. He examined the patient’s abdomen and extended the process to a clumsy grasping of (shall we say) the man’s nether regions. I thought it was odd but dismissed it from my mind. Many years later, I read in “The Times” that the doctor had been suspended from the Register for inappropriate examinations of male patients. In hindsight it all made sense. But even now I remember that doctor’s many great qualities: his charisma, kindness, his brilliant mind, his compassion. How could I not “see” what happened right in front of me?

We believe lots of things about those above us, especially in the Lord. Mostly we believe great things of them. Still.

Those of us who have been abused, may not even realise it for years. It’s hardly surprising that the majority who haven’t suffered have trouble shifting their view about previously esteemed Bishop Ball.

I believe the church is in shock about clerical abuse. We’ve all heard about the flight or fight response to danger, in individuals, but I believe groups also act as one in similar ways. But An oft forgotten threat response is “freeze”. Individuals freeze in threatening situations and so has the church.

Shouting ever louder about abuse scandals has barely made an impression on the immobile institution.

Freezing is a fear response. It is just too threatening to allow ourselves to believe our church leaders/doctors/presidents could be so flawed as to have done this/that. And even so they’re still good aren’t they?

The threat to group security grows as the survivors tell their stories, are sometimes and at long last believed, and it becomes increasingly obvious that the problem we just heard was the tip of the iceberg.

This knowledge changes us. It undermines the very structure of our lives, our belief systems.

We may understand and even accept just how bad things are but we cannot force this understanding on those around us. Boy how we have tried.

What we can do is work together to press forward with the truth about what has gone on. We can join together with those who are out there lobbying for initiatives like mandatory reporting, and as christians individually, love with a love we ourselves perhaps were denied.

To unfreeze the church will take a great deal of warmth. I do have hope that better leadership will prevail.

As leaders we could choose more accountability. Allow your team to veto certain decisions you make. I did this with tricky personnel decisions and found the results painfully irritating, but I didn’t regret it.

Let’s remember that most of these guys are scared. Scared of damage to reputations, massive financial loss (and it could be astronomical) , scared of closures, job losses.

Fear is a poor ally for us. But we can pursue honesty and transparency and begin to rebuild a better place. Ironically we have to provide a place of security. Of course many of us haven’t yet the strength for this. We’d like to be understood first. We could be waiting a long time. What ever we can do it’s best done together.

Well said.

What people forget is that human beings are not just good or bad. Good people do bad things and vice versa. We need to adjust to the fact that Peter Ball did good as well as bad things. It doesn’t mean the bad is less bad. They don’t offset each other. A thief may be loving to his wife and children, but he is still a thief. No judge would accept that that it is somehow ok because he’s kind to his family. We need to get our heads round that.

To be fair to myself my piece was an analysis of the known facts as revealed by the Gibb report. If these facts are incomplete, then I hope this will become apparent next week. I was not trying to claim inside information but to offer a distinct interpretative slant on the known reported claims. Whatever more is revealed next week, the extent of Ball’s abusing, the date when Carey knew etc, the claim that I made that Carey was defeated by Ball’s social and charismatic power does not become invalidated. The amount of guilt borne by Carey and others may change, but not the fundamental power dynamics which I attempted to describe. There was and is a clash of power systems and that is of interest to me and I hope to some of my readers.

Chris, I’m sure I’m not alone in being enormously grateful for your courage, along with others, in speaking about what you have experienced. I was horrified to read in February about your struggle to obtain counselling and hope that you are now getting support.

I attended a few days of the IICSA hearings in March and personally found it very helpful to see my own story within the context of a much bigger story about cover-up of abuse within the church. If nothing else it makes it easier for me to talk with family and friends about my experiences and for them to believe me, so you are doing a great service to others.

All good wishes for this coming week and for a flourishing life afterwards.

It’s going to be rough for those involved. My thoughts and prayers will be with you all.

Dear Chris, to quote Jayne Ozanne, addressing the Church at Synod , ” How do we say sorry?”

The company that Gibb is chair of ‘Skills for Care’ works very closely with SCIE who did the audits and is now doing the survey! All very cosy! I know this because I wrote to Gibb regarding my concerns about the audits and she wrote a rude reply back.The correspondence is with the IICSA solicitors but it’s disheartening to see how hard it is to get any real independence in the church, they are all linked in some way and all covering each other’s backs. Completely and utterly sick of it. Good luck Chris for next week – do a big sigh at Gibb for me if you see her – like your twitter page – thank you.

Saw your letter in the Church Times! Well said.

Some comments have had to be be removed by request for legal reasons.

I would like to reiterate my thanks and gratitude to all the victims/survivors of Peter Ball for speaking out about their experiences at such great cost, and send all good wishes to them both for the coming week and for flourishing lives thereafter.

You truly are appreciated.

There is much about this case which is deeply concerning, not least the fact common to many of these cases that because those who knew did nothing, further abuse was not prevented. However, there are other issues. It is not entirely clear from the Gibb report who knew what and when in the early years when concerns were first expressed. The Norwich Crown Appointments Commission were clearly not going to be hoodwinked some years earlier. However, the Gloucester Crown Appointments Commission almost certainly was. Why was this person translated to Gloucester? What did the references say? Of course we will probably never know. But as to who is still alive who was a member of that Commission, the two Chairmen are, Lord Carey and Lord Habgood. More pertinent, why was Ball nominated for Lewes in the first place? The Bishop of Chichester could not possibly (in my opinion)have been ignorant of the concerns. These questions are probably not top of the agenda, but they deserve answers.

Lord Carey is giving evidence to the IICSA enquiry on Tuesday morning, so some of the questions may be answered then. The enquiry is live streamed so you may be able to watch, if you aren’t otherwise engaged.

As to why Ball was appointed Bishop of Lewes: he was (and presumably still is) Anglo-Catholic and Chichester is predominantly a high church diocese; and there were persistent rumours about the diocesan. Gordon Rideout, who had already been court-martialled for abusing teenage girls while an army chaplain, was appointed to a Sussex parish years before Ball arrived on the scene. Rideout was found not guilty on that occasion, but it isn’t every diocese which would have appointed him so soon after that case had concluded. And a theological college principal who had resigned over sex scandals at the college, also was appointed to a Sussex parish. There is no suggestion this man had been involved in anything untoward himself, but he had tolerated such behaviour in others under his care.

I think there is probably a lot more to be told about Chichester Diocese, and the story goes further back than Ball – as you suggest.

It is just as well that God’s forgiveness is so large, and Jesus’ sacrifice all sufficient. The more I hear, the worse it gets. Lord, please be with all those involved next week.