During the past few days, we have heard of the death, at the age of 92, of Robert Graetz. Most of us (myself included) had never heard of Graetz until this notice of his death. His obituary, as recorded in The Times is, however, an inspiration to many of us, especially those of us seeking fresh models of Christian ministry for today. He followed a particularly courageous and costly path of discipleship. Through his ministry, he also helped to change the course of history in the United States. What he did and what he stood for stands out as a beacon of light. It shines in a dark world of terrible racial division and hatred that is still a threat to societies everywhere, and is found even inside our churches.

Graetz was a young white Lutheran minister who was sent to serve a black congregation in deeply segregated Montgomery, Alabama in 1955. The time and the place of this appointment suggest that Graetz was stepping into in a very difficult situation, especially for a first charge. Unlike other white Protestant denominations, Lutheranism had never been wedded to the racist narrative of some other Christian groups in the southern United States. The history of American Christianity and the way that Protestants in the South provided ideological support for the Confederate cause during the American Civil War, is a complicated one. Suffice it to say that some Christian denominations claimed to find scriptural justification for the institution of slavery. It is an area on which I have no specialist knowledge, so I have to pass over the topic with some generalities. As I understand it, some Christians in the 19th century also colluded with a mythical narrative which saw the European white races as being a people chosen by God to inhabit the new promised land of America. All the other races, native Americans, blacks and other non-whites were deemed to be second class, and some were fit only for slavery. I leave it to others to unpack this complex history of the ideas that have spawned notions of white supremacy. It does seem clear that part of this story has its roots in a distorted theological/biblical vision. The leaders of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, although they were not party to this white supremacy mythology, would still have preferred to send a black minister to Montgomery, but none was available. So Graetz entered an arena, every bit as dangerous to life and limb as those faced by the early Christian martyrs on their way to execution. The main difference was the fact that those who were to oppose him in his work with Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and other early heroes of black resistance, were in many cases self-designated Christians.

In 1955 the separation of the races in the southern States of the USA was virtually total. Restaurants, parks and transport were all segregated. Graetz was a front line witness to the now widely commemorated act of defiance by Rosa Parks, a member of his congregation, who refused to give up her seat to a white passenger. For this she was arrested, but the leaders of the black community began immediately to organise a boycott of the transport system. This lasted 381 days until the Supreme Court stated that segregated transport was unlawful. The boycott was organised by a new organisation, known as the Montgomery Improvement Association, run by another young minister, Martin Luther King. Graetz was a fellow organiser and on King’s committee. Graetz’s own car was put into extensive service, ferrying numerous black passengers as a taxi/bus service. This boycott was the pivotal moment in the national civil rights movement for the whole country.

Three days after Rosa Parks was arrested, Graetz stood up in his church pulpit and urged his congregation to join in the protest. As well as driving his neighbours around in his own car, he organised a car pool to help strengthen the protest. He also wrote to all his fellow white Christian ministers, urging them to show ‘Christian love’ by supporting the protest. None dared.

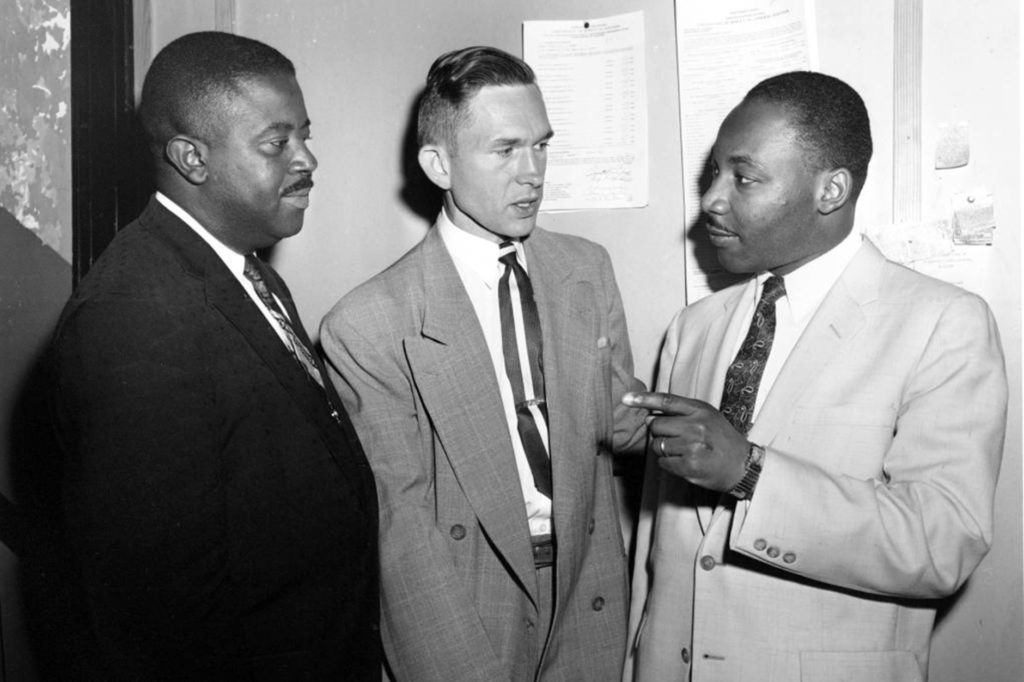

Being the only white person openly supporting the bus boycott, Graetz attracted attention. He appeared in newspaper photos next to King. White people who supported blacks were considered ‘worse than the black person’. His ‘taxi service’ attracted the attention of the police and he was arrested on one occasion. More serious still were rocks and bomb attacks against his house, not to mention numerous acts of vandalism against his property. All these events were going on against the background of Ku Klux Klan activity. Convictions for the Klan crimes were hard to achieve. White juries were reluctant to find accused white people guilty, especially when they were accused of damage to black property. On the same night that saw a serious bomb attack on Graetz’s home, the home of another prominent boycott leader, Ralph Abernathy and four black churches were also attacked.

The exact place of Robert Graetz in the overall story of civil rights in America is not one for me to write. Indeed, my writing about this particular individual is purely as a way of inviting my reader to think about Christian ministry taking place in a setting of extreme physical danger. One is forced to ask questions for which there are probably no answers. Should one ever go through such things with your own family being put at risk? The story of Martin Luther King is fairly well known and Graetz appears to have stood alongside him as a fellow minister. No doubt their friendship was able to do something to strengthen King’s resolve for what he had to do and to endure. But what comes over from Graetz’s story is the determination by a Christian minister to put the service of the people in his charge as a priority over every else, even his personal safety. In the rhetoric of many Protestant ministers there is a constant repetition of the desire to present the Gospel to ‘lost’ and fallen individuals. No greater need exists for humankind than to hear, to respond and be saved. Graetz had a different vision of ministry. He believed in the preaching of the gospel as a way to give new hope for this life both to individuals and entire communities. The Church and the Good News were about a better life for his listeners. They were being encouraged to work for this themselves in all their efforts to promote justice, equality and the overcoming of the abject poverty that in particular afflicted the black community. That makes him a hero of Christian ministry in my eyes, even though I have only ‘met’ him in the last couple of days through his obituary.

The idea that the Gospel or ‘Good News’ is about allowing the teaching of Jesus to change people so that they become instruments of society transformation is not in any way a new idea. In Matthew’s gospel this view of the meaning of the Good News is found in the judgement scene in chapter 25. The judgement that is made is not whether we have believed the right things, but whether we have been inspired by the Good News to do the right things, feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit the prisoners etc. The version of the Good News that tacitly supports white supremacy ideas is one that preaches a sanctified self-care at the expense of any necessary awareness, let alone service, of others. If the social activism of people like Robert Graetz is considered to be ‘liberal’ theology, then so be it. I would prefer to identify and be inspired by such a ministry which faced up to physical danger, calumny and hatred, to allow justice and love to win through. That is the legacy of Graetz. He showed a Jesus-like integrity of service that cared nothing for self, for power or material advantage. The love of God was a compelling reality in his life. With it he was able to stand firm and, in spite of his fears, make a distinct contribution to civil rights in America. He also serves as a model of integrity which Christian ministers can identify with everywhere.

Thank you Stephen, inspiring. I hadn’t heard of Gaetz before either, so glad to learn about his inspiring life and work.

Perhaps not liberal but liberational theology? We stayed in El Salvador on our travels, & Gaetz’s approach reminds me of the worker priests & Abp Romero.

We all owe a debt of great to people who show us how the gospel can bring transformational justice to our world today. Practical Kingdom theology. In its own way, this blog is part of that for me. Somewhere we can learn & debate the ideas & beliefs that inform our activism.

Oops sorry misspelt – Graetz.

I too was moved by the Times obituary – and wondered why I hadn’t heard of him before. What a great man.

Growing up in that States I sometimes encountered people, also calling themselves Christians, who would argue that black people were cursed because they were ‘sons of Ham’. Only they didn’t call them ‘black people’. They had less pleasant terms. Funny how they didn’t seem to notice that, according to the Genesis story of the Fall, all human beings are under a curse. That doesn’t authorise us to treat each other without dignity and justice.

A Florida high school I attended had the image of the Confederate flag let into the pavement of one if its main walkways. I was one of the few students who was prepared to tread on the flag – and I enjoyed doing it.

A particularly helpful recent analysis of American racism, including discussion of the theology justifying black slavery, is “Caste – the lies that divide us” by Isabel Wilkerson

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Caste-Lies-That-Divide-Us/dp/0241486513/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=caste&qid=1601135941&s=books&sr=1-1