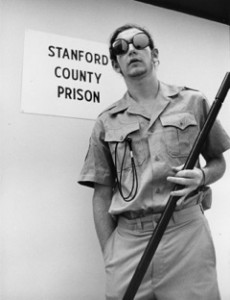

Last week I wrote about the ideas of Lord Owen about the way that an individual could be corrupted by holding a position of great power in politics. Owen referred to this as ‘hubris syndrome’. This study is, in many ways, backed up another piece of research undertaken in the early 70s, known as the Stanford Prison experiment. The author of this experiment, a social psychologist called Philip Zimbardo, wanted to see the extent to which ordinary people might change when put in a new unfamiliar situation. He chose twenty male volunteers, from a student population, who were screened for obvious mental disorders. Then these volunteers were divided into two groups for the purpose of the experiment which was simulate the experience of prison life. One group were to act as guards while the other group were to be the prisoners. To make the experiment realistic, the ‘prisoners’ were taken into custody by serving policemen before being deposited in the cellars of a university building at Stanford under the care of those designated as guards. The crux of the experimental finding was to observe how both groups threw themselves into role. The realism of the roles that both were playing was so vivid that the experiment had to be cut short lest one of the participants suffer mental collapse. In summary the ‘guards’ started to act with cruelty, using their authority to undermine the ‘prisoners’ as much as possible. No physical punishment was permitted but mental and emotional abuse became rampant. Everyone in the experiment knew that they could leave at any time but none did, apart from one prisoner who started showing signs of complete mental collapse. He was withdrawn for his own safety. The whole experiment was meant to go on for two weeks, but in the end it was stopped after five days when Zimbardo’s girlfriend recognised that there was a rampant evil in the environment that was affecting even the observers. Cruelty and an enjoyment of inflicting pain seemed to have taken over the minds of the ‘guards’ while the ‘prisoners’ seemed to have forgotten how to stand up for themselves to withstand this onslaught.

Last week I wrote about the ideas of Lord Owen about the way that an individual could be corrupted by holding a position of great power in politics. Owen referred to this as ‘hubris syndrome’. This study is, in many ways, backed up another piece of research undertaken in the early 70s, known as the Stanford Prison experiment. The author of this experiment, a social psychologist called Philip Zimbardo, wanted to see the extent to which ordinary people might change when put in a new unfamiliar situation. He chose twenty male volunteers, from a student population, who were screened for obvious mental disorders. Then these volunteers were divided into two groups for the purpose of the experiment which was simulate the experience of prison life. One group were to act as guards while the other group were to be the prisoners. To make the experiment realistic, the ‘prisoners’ were taken into custody by serving policemen before being deposited in the cellars of a university building at Stanford under the care of those designated as guards. The crux of the experimental finding was to observe how both groups threw themselves into role. The realism of the roles that both were playing was so vivid that the experiment had to be cut short lest one of the participants suffer mental collapse. In summary the ‘guards’ started to act with cruelty, using their authority to undermine the ‘prisoners’ as much as possible. No physical punishment was permitted but mental and emotional abuse became rampant. Everyone in the experiment knew that they could leave at any time but none did, apart from one prisoner who started showing signs of complete mental collapse. He was withdrawn for his own safety. The whole experiment was meant to go on for two weeks, but in the end it was stopped after five days when Zimbardo’s girlfriend recognised that there was a rampant evil in the environment that was affecting even the observers. Cruelty and an enjoyment of inflicting pain seemed to have taken over the minds of the ‘guards’ while the ‘prisoners’ seemed to have forgotten how to stand up for themselves to withstand this onslaught.

When the experiment ended, Zimbardo expected that the those among the guards who had behaved particularly badly would eventually be shown to have a recognisable pathology over the long term. But, although he followed his ‘guards’ over thirty five years, none ever showed in their lives any tendency for cruelty, either in the family or in the work place. It seemed that the sociopathic behaviour displayed had been provoked entirely by the experimental environment. In short the evil that was unleashed through the experiment was a product of the artificial environment. Absorbing expectations as to how to behave in fulfilling a role, had completely taken over their personalities.

In his reflection on the experiment after forty years, Zimbardo in his book, The Lucifer Effect, wants to alert the reader to the enormous power of situations and the way that they can overwhelm the consciences or what he calls the innate ‘dispositions’ of the participants. He sees similarities with the situation at the Abu Graib prison during the Iraq war where ordinary soldiers committed offences of cruelty and humiliation against their Iraqi prisoners. While it would not be right to declare the perpetrators free of all responsibility, the situation they found themselves in was a mitigating factor in their defence. This should to be taken into account.

Why is this research of interest to our concern for abuse and manipulation? It is because churches sometimes become ‘total’ environments where people behave in ways that not necessarily in accordance with their normal nature. The situation or the environment becomes the dominant reality. This may not necessarily lead to immoral or cruel behaviour, but there are a variety of other ways for people to behave out of character in a group situation. These may involve regression, immaturity or inappropriate dependency on a leader. Few manifestations of this kind of group behaviour are in the individual’s best interests. The zombie-like convert that we may meet on a street corner muttering his pious platitudes may simply be acting out the expected personality that his group may have placed on him. The earnest Christian who treats your questions about the Bible with undisguised hostility or suspicion may once again be expressing an aspect of some sort of group personality. He or she is so much a product of group conditioning that he does not have any sense of a right to an individual opinion.

Zimbardo’s research of forty years ago could not be replicated today because of ethical considerations. But the research remains as a terrifying reminder of what can happen when a group’s norms and assumptions take hold of individuals so that they act out the norms of the group rather than their own. Social influence is indeed a powerful and potentially catastrophic power. We must make sure that our churches do not become places where people lose their separate selves and become part of the herd.