Some eleven years ago my wife and I moved to the city of Edinburgh. At first, as in any new city, we found ourselves easily lost in getting from one place to another. But over a period of time we began to see the connections between one landmark and another so that setting out for a new place no longer filled one with dread that we might end up in a totally strange part of the city not knowing in what direction to go. Certain parts of the city did remain strange to us and even after seven years I dreaded being asked to officiate at a particular crematorium on the far side of the city.

Some eleven years ago my wife and I moved to the city of Edinburgh. At first, as in any new city, we found ourselves easily lost in getting from one place to another. But over a period of time we began to see the connections between one landmark and another so that setting out for a new place no longer filled one with dread that we might end up in a totally strange part of the city not knowing in what direction to go. Certain parts of the city did remain strange to us and even after seven years I dreaded being asked to officiate at a particular crematorium on the far side of the city.

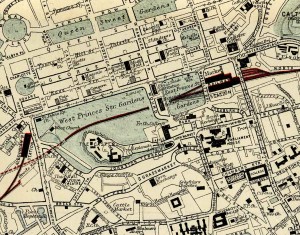

The task of getting to know a place involves a process of internalising a map inside of one’s head. The map that one carries around inside is no longer a map marking particular places but it also includes the connections between them. One learns a series of alternative routes to get from A to B. You have successfully put each landmark into a setting of relationships with other landmarks. To know a city is to understand how one place connects with everywhere else.

The task of getting to know the Bible is one that goes far beyond being able to quote particular passages. The Jehovah’s witnesses who bombard you with texts taken out of context, are rather like travellers who claim to know a city because they have visited certain landmarks. Metaphorically speaking they were taken there by coach and never understood how they got there. Far too many preachers endlessly quote high sounding passages from a pulpit as though that concludes any discussion. But every text has a setting and a context. Every text is linked to other texts and not to understand these connections is to show little understanding of the whole. Just as the map needs to show the roads that connect the landmarks, so the Bible texts and passages need the context in which they belong as well as their connections with the whole.

One of the great ‘aha’ moments in my own study of Scripture was the realisation that Paul, no less, evolved and changed in the time he spent writing the letters. One is able, for example, to trace a line of development in the way he understands the end of the world. The early language of I Thessalonians uses fairly crude literalistic language of apocalyptic to describe the coming of Christ and the way that people are physically ‘raptured’ to meet him. The language of I Corinthians 15 shows that Paul has re-thought his teaching as he realises that there are problems in his earlier ideas. Now he proposes that the earthly or physical body is raised as a spiritual or imperishable body. To use our map language, one is being presented with an understanding of the way that these two sections of scripture are connected. The route that joins them together is the idea of an evolution of thinking by Paul.

The problem about thinking about the Bible as being like a map, is that very people have cottoned on to this very basic idea. Even those who have years of study still seem very adept at treating a particular passage as though its context did not matter. And yet every single passage is rooted in a context of history, theology and culture. It will of course never be possible for anyone to know all that there is to know about the detailed map of the Bible and to see all the connections. But equally it would be wrong to pretend that that there is no map, that the Bible is a series of disconnected blobs of truth scattered over the landscape.

The study of Scripture is to see, even in part, the way that the idea of a God who is concerned for the human race takes shape. Different aspects of this revelation are discernible at different times. Different insights, not all of equal value are presented to us within the text. The notion of inerrancy, which we have discussed many times before, destroys the richness and complexity of the way that truth is handled in the text. We need to affirm the connections that exist within Scripture that allow us to understands the untidinesses and even contradictions of the text. There are no simple or ‘common-sense’ solution to the many problems that confront the reader who really wants to understand. The only way forward is to study at depth or to find a teacher who also wants to see the Bible, not as blobs of truth, but as vast interlocking system of reflection that presents to us some of the ultimate questions and the way that human beings have tried to respond to them in the light of their experience. Truth will always be more than uttering platitudes. It will involve detailed and painstaking engagement with the detail of the maps of truth that we have in Scripture.

Thank you Stephen – thoughtful as usual. As a student I remember reading the fifty chapters of Genesis in four days, then starting again on day five, and keeping that up for three months. This really helped to get to understand its geography in the way you describe. Now if anybody wishes to make a point quoting Genesis, I feel on firm ground! I did it for other biblical books as well, but I never got round to Deuteronomy, I confess.