The rights now afforded to women by the church and the wider society would have been unthinkable only a century ago. We, in the Anglican church in the UK, are celebrating the recent vote to allow women to be bishops but we forget how much the church used to stand at the forefront of opposing even the very idea of women having rights or status in a male dominated world. If we deplore the attitude of some Muslims towards their women folk, we must not forget that in the 19th and early 20th century, the rights of women were virtually non-existent in Christian Europe and America.

In America, the National Woman Suffrage Association Convention was founded in 1885. One of the chief weapons used against this movement was, according to an early speaker Elizabeth Stanton, religion. She declared how the ‘Bible was hurled at us from every side’. In the next generation, in 1921, the power of religion was used to shut down Margaret Sanger’s public meeting in New York on birth control. The Equal Rights Amendment in the States was finally passed only in 1972. It had been presented to Congress for the first time in 1923 but had been bitterly opposed by congregations from Catholic, Mormon and Protestant groups. The Suffrage, the right to vote by women, was also long contested. The opposition to these ideas was in part sustained by the endless repetition of the familiar Pauline texts which appear to demand the silence and subjugation of women.

Two pioneers of the 19th century against the institution of slavery in America were two sisters, Sarah and Angelina Grimke. Although they spoke only to audiences of women, the Congregational Church of Massachusetts sent out a letter in 1837 censuring them and declaring that they would ‘fall in shame and dishonour into the dust’. 300 men walked out of a meeting in New York in 1840 to protest the presence of one woman, Abby Kelly, on the committee of an anti-slavery group. In every case the participation of women was understood to be a ‘defiance of the New Testament’. A women’s rights convention in New York in 1853 brought out mobs of men, clergy and their supporters to sabotage the proceedings ‘with hisses, groans, stamping and ridiculing remarks’ bringing the proceedings to an end.

As a matter of record, it was women who were not members of organised religious groups who did the most to further the cause of women’s rights. A colleague of Elizabeth Stanton, Matilda Gage, wrote the influential Women Church and State. This owed little to religious ideas and she and her supporters would have been described as freethinkers. Another freethinker, Charlotte Gilman wrote: ‘one religion after another has accepted and perpetuated man’s original mistake in making a private servant of the mother of the race’.

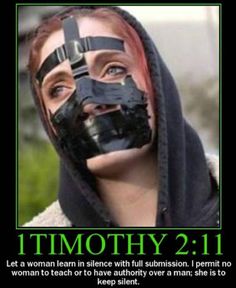

I bring these various incidents of religious aggression against women before the reader to remind us all that attitudes on the part of Muslims towards women were part of our societies for a very long time. Not only were they endemic in the societies of 100 years ago, but the echo of the same attitudes is with us today. The open opposition to the concept of equal rights for women in society is not often articulated by religious groups but hidden misogyny still stalks congregations up and down the land. The basis for this opposition is to be found in the application of the identical Pauline texts that were thrown at the women’s rights pioneers. For the sake of tidiness I list them here. I Corinthians 11. 3, 8-9, I Corinthians 14. 34-35 and 1 Timothy 2.11-14. Whether Paul is the author of 1 Timothy is not here important because the writer is clearly following the Pauline tradition in this matter.

In my previous post I suggested that the way to deal with difficult texts is to apply the principle of seeking to establish the wider context. In the first place as a counter-balance we have the remarkable statement by Paul that in Christ, there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female but all are one in Christ. This appears to be Paul speaking in a lyrical frame of mind, while the ‘anti-women’ passages seem to reflect a far more sober approach. Paul’s writing often seems to touch heights of inspired poetic grandeur while at other times he comes over as rather pedantic and legalistic. While this comment is subjective, I invite the reader to contrast the poetic power of Romans 8 and the dry argumentation of chapter 9. Still more important for our desire to qualify the Pauline sayings about women is a cursory glance at the attitude of Jesus himself. The gospels cannot but reveal an approach to women (and children) by Jesus which was revolutionary in the extreme. I have not read feminist readings of the Bible, but anyone interested will have no difficulty in locating all the occasions where Jesus turned upside down the conventional patriarchal attitudes to women that were part of all the cultures of the ancient world. Certainly it can be said that there is nothing about Jesus and his approach to women that gives the tiniest support or encouragement to the attitudes that Paul seems to possess in the ‘proof-text’ passages mentioned above.

The anti-women rhetoric of yesteryear has given way to hate-filled rhetoric against same-sex relationships. Uncomfortably for those who follow the line that ‘the Bible clearly states …’ , exactly the same type of arguments are used to make their points. In another hundred years time, I hope that we will be looking back to this age and saying: ‘How could the Christians of that time really have argued in this way?’ The Bible is a document to read in order to understand the mind of Christ, but let us always read it with care, sensitivity together with an awareness that we might be reading our own political and psychological issues into the text when they are not there.