Followers of this blog will have noticed that I do not resonate with various of the standard statements of Evangelical theology. In particular I have shown my unease with the standard, and to some, essential explanation of the death of Christ as a substitutionary atonement. My main objection to the doctrine is biblical. Granted that the doctrine can be read out of certain biblical texts, there are also other models. Logically, to be properly ‘biblical’, we should be prepared to hold all the models together and see them as different but complementary attempts to explain something that is by nature beyond explanation. My particular favourite model is that given in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Christ is seen to fulfil the sacrifice of the Day of Atonement. By his sacrificial death, he enters into the Holy of Holies, the actual presence of God. We who are his followers go with him into the heavenly realms. This theology is reflected in the passage in Hebrews 4.14, ‘Since then we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast our confession…..’

Followers of this blog will have noticed that I do not resonate with various of the standard statements of Evangelical theology. In particular I have shown my unease with the standard, and to some, essential explanation of the death of Christ as a substitutionary atonement. My main objection to the doctrine is biblical. Granted that the doctrine can be read out of certain biblical texts, there are also other models. Logically, to be properly ‘biblical’, we should be prepared to hold all the models together and see them as different but complementary attempts to explain something that is by nature beyond explanation. My particular favourite model is that given in the Epistle to the Hebrews. Christ is seen to fulfil the sacrifice of the Day of Atonement. By his sacrificial death, he enters into the Holy of Holies, the actual presence of God. We who are his followers go with him into the heavenly realms. This theology is reflected in the passage in Hebrews 4.14, ‘Since then we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast our confession…..’

A second reason for querying the standard protestant explanation of Jesus’ death is that there is another branch of the church, the Orthodox, that have never given much attention to our Western preoccupation with doctrines that have as their aim the avoidance of Hell. I cannot of course in this short piece, do more than outline these differences but I want to begin with a much overlooked text in 2 Peter 1.4 that has inspired the Orthodox to develop theology in a different direction. The passage reads as follows: ‘Through these (power and knowledge) he has given us his very great and precious promises, so that through them you may participate in the divine nature and escape the corruption in the world caused by evil desires.’ This passage seems to have been unnoticed by the Augustinian/Calvinistic strain of Christianity that wanted all Christians to ‘grovel’ in their utterly depraved wickedness. Instead of being required to wallow in filth and depravity, the Christian is being invited to contemplate the possibility of sharing with Christ the divine nature itself. The same theme was expressed by Athanasius who in around 350 AD summed up the Incarnation in the famous words, ‘God became man so that man might become God.’

The Orthodox have developed a theology that is optimistic and more focused on the potential of human beings on their Christian journey than in emphasising how they are a hair-breadth away from Hell. I am one of many people in the West who appreciate these positive themes within Orthodox theology, while recognising that it has suffered from many reactionary conservative forces over the centuries that sometimes make it difficult for the Westerner to penetrate and properly appreciate it. But I would like to continue with this theme of an optimistic, hopeful theology about humankind that I find in the classic presentations of Eastern Orthodox teaching.

Orthodox theology has never downplayed the fact of Original Sin and indeed the disobedience of Adam is spoken about in many texts in strongly literal way. But although there is agreement with the West over the way that corruption has, through Adam, entered the entire human race, there is a softer tone in this presentation. After the fall, humankind still has some freedom and there is nothing to suggest that total guilt and depravity is what marks the human race. When presenting the life, death and resurrection of Christ, the Orthodox put a greater emphasis on the Resurrection than on the crucifixion. The Resurrection is the climax of his life and the full revelation of the way that God and the human race are joined in a burst of glory. The story of the Transfiguration is also celebrated as an anticipation of this triumphant proclamation that God has broken into our material world. The Crucifixion is also celebrated but it is never allowed, as in the West, to be separated from the Resurrection. The two belong together.

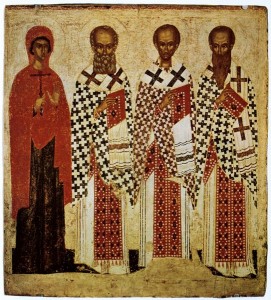

The life of the Christian following the Resurrection can be summed up in this single word implied in the 2 Peter passage, ‘deification’ or participation in the divine nature. The Orthodox point to other New Testament passages that imply this idea, notably the passage from the ‘High Priestly prayer’ in John 17. ‘As thou Father art in me and I in thee, so also may they be in us.’ Deification is a strong theme through the centuries and it undergirds what can be called Orthodox mysticism. The Orthodox also have a strong sense of the way that the human body is to be involved in spiritual practice and the literature is full of accounts of the bodies of saintly people glowing in a physical manner. The tradition of icon painting also shows how the saints and men of prayer possess the radiance of a heavenly light.

The emphasis on ‘deification’ or the transformation of human beings through prayer and attention to the sacraments of the church is a simple one. I cannot of course discuss it in any further detail at this point, but to repeat what I said earlier that it is a hopeful and attractive presentation of the Christian faith. I share it with my readers because it summarises part of the reason why I am so critical of other presentations of the faith that use fear and the threat of deep despair in promoting the Christian faith. Perhaps this short piece will help some of my readers to see that Christians who promote their version as the only version of the faith are simply wrong. There are versions of the Christian faith, far older than our own, that have nothing whatever to do with the squabbles in the West around the time of the Reformation. To breathe Orthodoxy, even if only for a time, is like breathing fresh air, after being for a long time in the fug that we call Western Christianity. From the Orthodox point of view, having never known a Reformation, our theological debates all seem rather petty and provincial!

I have often read The Book of Hebrews through at one setting. The author clearly believed in the substitutionary atonement to my mind. See 9:27 – 28. I don’t understand your notion of multiple models, but if there are such, then picking and choosing between them according to taste seems unwise. We need them all.

I share your dislike of abject fear being used as a motivator in evangelism, indeed in any circumstance. This is the method of dictators. Having said that, I have been attending evangelistic meetings for fifty years, and I have yet to hear fear of hellfire even being mentioned. The notion that people are being driven into Christian belief through cringing fear has no basis in what I have witnessed, but then I have not attended cult meetings so maybe it goes on and has passed me by. Target your fire at genuine instances of abuse.

I think there is a balance to be struck in the giving of warnings. A notice reading “Danger cliff edge” placed in an appropriate cliff-top position strikes me as being merciful and kind rather than oppressive and harsh. Personally, I regret that Jesus’ teaching on hell, the wrath of God and eternal punishment have not been mentioned more often in the circles I move in. Our society seems to have forgotten them. See Matthew 5:29 – 30, John 3:35 -36, Matthew 25:31 to 46.

While I agree with you that we must balance the different analogies and metaphors that liken the death of Christ to a sacrifice, it is also important not to get stuck with a single model. The so-called substitutionary theory seems to imply that Christ’s death was a sacrifice to appease or propitiate the ‘anger’ of God. If we insist on this as the ONLY interpretation and also part of the belief system that is essential if we are to be ‘saved’, we are wrong on two counts. First of all I have made the point that such a doctrine can never correctly be presented as the only biblical model. I hesitate to name all the other sorts of sacrifice that undergird the biblical text but mention just two. First we have the ‘covenant’ sacrifice that is understood in the Eucharist narratives in Matthew and Mark. That is nothing to do with ‘propitiation’. Secondly we have the Passover sacrifice. This is also picked up by Paul and John. The propitiating here was not towards God but to the destroying angel. The second count is that even if we have a preference for the propitiation model endlessly repeated in evangelical sermons, we need to look very carefully at the biblical texts to see what they actually say. Here I follow Frances Young’s careful study. She says that the emphasis should be put on the fact that God in the Old Testament provides means through which sin can be cleansed, not as a means to appease his anger. When Hebrews (10.2-4, 14) talks about Christ’s sacrifice, he assumes the point of blood is to put away sin and cleanse conscience not to propitiate God.

I offer this more detailed response to the issue because it is at the heart of a distortion that many people carry because of unbalanced teaching over hundreds of years. Because I firmly believe this to be the case, this will explain why I am passionate to put out another point of view. If one person can be liberated in part from this claustrophobic insistence on the correctness of only this doctrine, then the effort of writing this is worthwhile.

You are fortunate indeed never to have heard about hell-fire in Christian sermons. I heard it in a sublimated way from David Watson as a student and he was then a leading star in the evangelical firmament. Chris can fill us in on his experience. I indirectly only hear it now, it is true, on religious broadcasting. It is out there, I promise. I read Jesus’ teaching as being about encouragement to follow in a particular direction than telling us about the dire consequences of not going in that direction. For me the word ‘saved’, as used by Christians, has its own undercurrent of threat. It may not produce ‘cringing’ Christians but it still creates fear in some.

Stephen,

thanks for this thoughtful response. Appreciated. There are clearly levels of this teaching that I have never considered, and personally I am happy with “Jesus died so that my sins could be washed clean” and leave it at that. What I really enjoy is looking at the Greek and Hebrew and the papyrology etc. I was never that keen on doctrine.

I understand that what you are commenting on is the attempt to say “So and so is the only possible way of understanding this” when there may be other possible ways of looking at it. I think you make a good point here.

I heard David Watson twice when I was a student. I recall thinking he looked like a GP when I first saw him.

Please keep writing!

I have heard hellfire sermons. I remember a Scottish preacher oozing buckets of sweat. I am sure he was utterly sincere. When I finally got to read “The gospel of the hereafter” by J Paterson Smyth I learned that things always have another side.

David. Thank you for your response. One of my reasons for wanting to explore ‘other possible ways of looking at it’ is not just out of intellectual curiosity. It is because that unless we have people prepared to go out of their customary ways of looking at things, we end up in a world even more mired in disputes than it is. That is why the gift of imagination is such an important part of conflict resolution whether in international relations or religious disputes. The joy of learning other languages is that when you become a little proficient, you begin to see things with the eyes of other cultures, whether living ones or dead ones. Ordinary things change their character when spoken about in another language. We need to retain always our sense of provisionality when we use words. Communication is always going to be hard and so we must have a sense that we may not fully understand what another person is trying to say to us. Word and concepts are very malleable things and we must always make allowances for that.

Thanks, Stephen. Very interesting. I am reminded of the person who declared with great emphasis “All statements are meaningless!” only to receive the reply. “Well, that includes your statement too then, so why say it?” Humility seems to be the order of the say.

Whatever our differences love and respect is closer to the way of Christ. This blog is about finding every opportunity to love and help in practical ways.

There has to be something wrong with the view that God wanted to kill someone, and didn’t much care who! And granted His known views on human sacrifice, strange in deed that He demanded it in this case. And most people who claim to accept that model, don’t really think about it. They really have no idea how it sounds to those outside the church.

As often is the case I think Chris makes a very important point. Though I think it is helpful to air differences of interpretation or of understanding, the key issue is to think about how we are being heard, and if Love is not present we have lost whatever argument we may put.

And as usual four of my five fingers are pointing back at me – so if I have offended anyone at any time I ask forgiveness.

Thanks Dick, Christ prayed that there would be a unity a ‘oneness’, so we know if that is our aim, then He is with us in that attempt. Sooner or later opposing sides must talk, one day they will of course but, I fear it will be too late for me to see.