Today (Tuesday) Andrew Graystone has sent a short pamphlet to every member of the Church of England General Synod which is meeting this week in London. https://www.thinkinganglicans.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Stones-not-Bread-Revisited.pdf The booklet is entitled We asked for Bread but you gave us Stones. One year on. It is a follow-up to the one produced a year ago at the London General Synod which I attended as a visitor. This was my way of showing solidarity with a small group of survivors who were gathering to make a protest. This protest was to coincide with the debate that was to take place on safeguarding in the context of the then upcoming hearings by IICSA on the Church of England.

The situation at this February’s Synod is that there is no scheduled debate on the topic of safeguarding. It may be that the word safeguarding is not even mentioned. Several questions on the topic have been put, but given the fact that they appear as questions 95 and 96 on the Q & A document, it is probable that any supplementary follow-up points will be crowded out by other topics. The Church of England is giving a great (disproportionate?) deal of energy to transgender issues at present

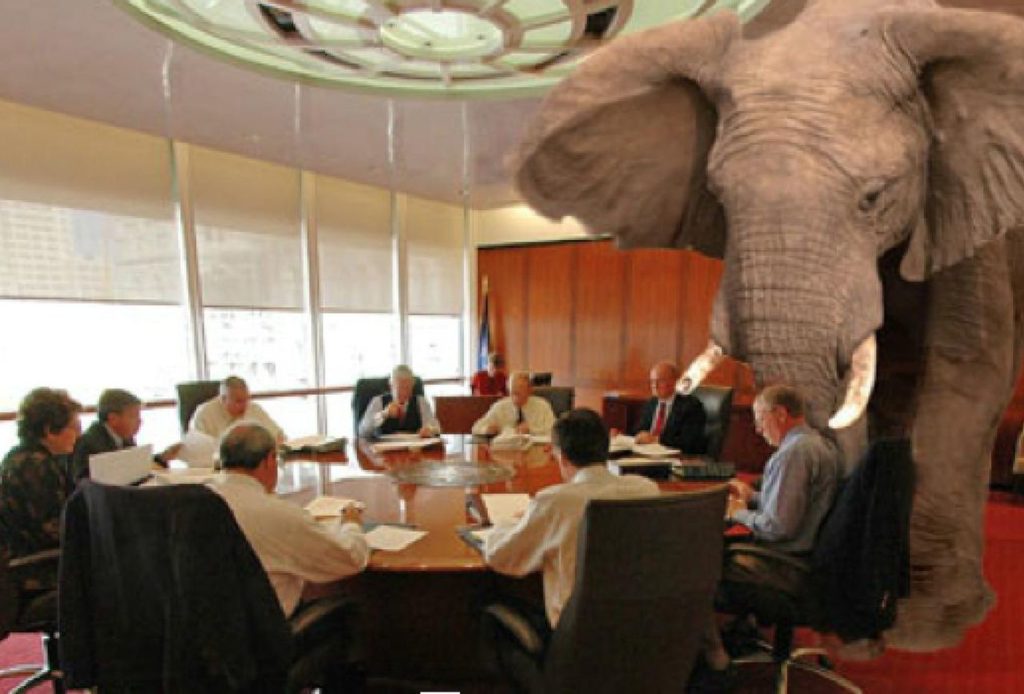

To return to Andrew’s booklet. The second page is an introduction to survivors’ testimonies, and he makes a telling comment about the elephant in the chamber. This Synod is due to debate evangelism, a term that implies that there is an audience out there waiting to hear what the Church has to say. This potential audience, unlike the Church itself, sees only a rather large elephant when looking at the evangelising community. This all too visible elephant is the fact that the church continues ‘to re-abuse and neglect its own victims’. Andrew goes on ‘You cannot preach repentance until you have repented. You cannot speak about the love of God whilst you treat survivors with cruelty.’

This second edition of Bread and Stones then educates the reader through a series of vivid testimonies in case the evil of what is going on some parts of the church has been forgotten. The elephant, so visible to the general public, is carefully described. No reader of the booklet can make the excuse that, somehow, they were unaware of the problem. Last July Jo Kind, a survivor, spoke to full Synod at its meeting in York. She received a welcoming response by members. It seemed that Synod might finally be ‘getting it’ over the issue of the importance of dealing properly with survivors. Sadly, Jo reports in the booklet that ‘the treatment meted out by the diocese since then has been terrible. Just when there seemed hope of openness and reconciliation, I felt mistrusted and controlled.’

The insight that Good News will never be heard by our nation until the Church gets things right over abuse is an important one. The failures that are recorded which lead to ‘re-abuse’ are not inadequate compensation payments, but mostly simple failures of compassion and human contact. The defensiveness towards victims by members of the hierarchy is particularly striking. Broken promises, delay and secrecy litter the accounts made by the ten survivors who have contributed to Andrew’s booklet. Last month the Archbishop of Canterbury made a telling statement in an interview in the Spectator which seemed to show a real understanding of the issue. He said ‘we have not found the proper way of dealing with complainants …. not telling them to shut up and go away, which is what we did for decades. Which was evil. It’s more than just a wrong thing: it’s a deeply evil act.’

This statement by the Archbishop sadly still reflects the present reality as far as the ten survivors represented in the booklet are concerned. One male survivor asks the question. ‘Has anyone seen a positive testimony of a survivor engaging with the Church of England?’ The question is unanswered but clearly, if any such positive testimony were to be had from among this cohort of survivors, it would have been recorded.

What do the survivors look for? Speaking from the evidence of the two booklets, as well as my own engagement with survivors, there seem to be certain simple things that are demanded. The first is transparency. Too many letters and communications seem to disappear into filing cabinets, or possibly shredders, where they can be forgotten or ignored. Making a serious complaint against a church leader should engage the minds of those who manage the church with a compelling urgency. While some aspects of the process may have to be kept confidential, the main thrust of the enquiry and process should be shared as far as possible with the victim. The police treatment of victims seems to be able to combine the pursuit of justice with an openness of information for the victims. Certainly, openness and good communication are aspects of caring that should be able to exist in a church that speaks about love.

The second part of the treatment that survivors need is even simpler. It is human care and concern. The first thing that any human being has to offer to another who is going through a crisis is the hug or embrace. Why is it so difficult for leaders to show ordinary human compassion when a story of abuse emerges? Even when these stories are decades old, the survivor needs to feel that he/she will encounter human sympathy. The old excuse that such human compassion might compromise legal processes has been shown to be an urban myth. If it is not dead, the latest published advice from the Ecclesiastical Insurance company should have finally killed it off. Love shown to a victim does not make a church liable for an increased pay-out. It is striking that of the ten victims recorded in Andrew’s booklet, not one in fact mentioned compensation. Even if financial need is there among their requirements, it is not by any means at the top of the list.

I hope that all members of General Synod this week will read Andrew’s booklet. I hope also that the hierarchy of the church will listen better to these survivors. Andrew reminds us that ignoring the elephant in the chamber could prove very costly indeed for the church and its long-term survival. Recognising this evil, the abuse and re-abuse of victims, is an important first step. In many ways it is, arguably, the most urgent task for the church today.

In not recognising the evil of abuse on their doorstep, church leaders are condoning it.They are saying that the abusers are innocent so I guess they see the victims as liars. If they cared about the victims the church would help them. But this isn’t happening. This is a very tragic state of affairs for the church.

You make a fascinating point about compensation, that for most people it is not the main concern. ‘Money can’t buy me love’ by the Beatles comes to mind.

Call me an old cynic, but assuming that what we want is to make them change, having to pay compensation is the incentive that might work! If you have to pay quarter of a million to compensate for a pension not paid because the victim gave up and left, maybe you’ll want to avoid incurring that in future. We already know that they don’t do anything out of either Christian charity or common decency. Money talks!

I’m wondering whether the diocesan bishop who sent me a “Shut up and go away” letter 14 months ago has realised his error yet, or whether any of his colleagues whom I informed have raised the matter with him.

I would very much hope his colleagues have raised it with him, but sadly I wouldn’t count on it. And if he/she had realised their error, they ought to have apologised to you.

Why can’t they admit they’re in the wrong? (rhetorical question, I don’t expect an answer!)

Whatever else a “shut up and go away letter is”, it is also very shortsighted: I might have “gone away” from trying to communicate with the bishop but I am simply communicating about the cover-up elsewhere.

They seem to be very slow to understand that. They think we’ll just go quietly, and we won’t.

They’re not bothered. So long as the stipend still goes into the bank every month.

Increasingly negative reporting on the response of the church like Bread and Stones is beginning to stop people reporting, something I have personally witnessed. Not only is that a win for the church but is counter productive for survivors.

I have had brilliant responses from the church and appalling ones, so similar to any other institution. Reporting to statutory services as Bread and Stones suggests is pointless and can be as equally abusive as the church response unless the person is a CSA survivor, or victim of an actual crime, and the vast majority of survivors aren’t, in the eyes of the law.

Reporting has to be balanced, and people who have had good experiences actively encouraged to tell their story.

Hi Trish. Good point. But I think everyone needs to be allowed to show their own experience. Hearing that I’m not the only one being treated in an uncaring way helps me feel less alone. And more serene, because I haven’t been picked on, it’s just the default position, not personal. But yes, we need to hear the positives. That gives hope.

Totally agree Athena but no one is interested in my good experiences or praise of some DSA’s, it just isn’t’ what people want to hear even though building on those positives could actually move the dialogue on as nothing that is being done at the moment is working. I think when things go well the church needs to hear that too, it’s a bit like training your dog!

I suppose that if your experience is bad, having someone else saying things are fine for them isn’t always what you want to hear! Especially if you’re still in the stage of wanting sympathy. Hope all’s well with you Trish.

Plodding on Athena thanks still trying to resolve my case. I do absolutely hear what you are saying but can I just run my thinking by you. When I have been responded to well it is because another diocese has dealt with my complaint. I have been responded to appallingly by my own diocese but move away from that very claustrophobic way of dealing with things and the response improves because the dynamics change. That has been extremely hard to achieve and I am very grateful to all staff that has withstood the horrendous bullying and threats from my diocese and NST to achieve that, but there is some indication that it works. Other dioceses than the person’s own dealing with their complaint. I am not talking long term solutions just better responses for people in need, what do you think?

Immediate response, bad technique!, I now feel like one of a team. I feel liked and included. I’m still waiting to be licensed, DBS! Why does it take so long? But, no one has ever apologised, no one has ever been pro-active and offered pastoral care, I’ve had to ask. So, yes, good responses from new people do help, immeasurably. But they don’t wipe away what they did to me. My case is not the same as yours, of course. But bullying has changed the course of my life, and did me great harm from which I am still recovering. I guess I think we need both?