One of the benefits of studying the Old Testament as a student was to have had what is known as ‘source criticism’ explained. Source criticism is, in brief, a way of discovering the underlying origin of some of the material in the book of Genesis. It helps to explain some of the anomalies you find there. You have, for example, a sudden change in the text from a word meaning God (Elohim), as in the first chapter to another quite different word sometimes translated as ‘the Lord’ (Yahweh). A detailed and close study of the narrative also picks up strange shifts in the story line. At one moment in chapter six Noah oversees the animals entering the Ark two by two. Then in the following chapter you find that the author is insisting that seven pairs of ‘clean’ animals entered the Ark. Such contradictions break up the flow of the narrative and must cause problems for anyone who insists that Moses wrote every word. The ‘source criticism’ hypothesis offers the simple common-sense explanation that the author/compiler is making use of several distinct sources. This allows us to account for the changing names of God, the contrasting creation stories and the discontinuities that we find in the story of Noah. The Genesis author was, in modern terms, a ‘cut and paste’ writer who freely used a variety of sources. There were no rules about plagiarism in those days.

A detailed study of the text of the New Testament also throws up some fascinating observations. The first three gospels, known collectively as the Synoptic Gospels for their similarities, can be shown to have borrowed material from one another, particularly Matthew and Luke. These two also frequently made use of Mark. The parallels are so strong that it is suggested that Mark’s gospel was available to Matthew and Luke in its written form. There is also another hypothetical written gospel of Jesus’ sayings and actions which no longer exists but it is a common source for sections for both Matthew and Luke. It is given the name Q, from the German word Quelle or source. The details of these discussions concern us here only as an introduction to the thought that all English prose can be examined when we want to determine authorship or suspect things like copying or plagiarism. Style, distinctive vocabulary and the use of particular phrases are all tale-tale marks of each individual writer. We can normally tell when one person is using text that originally was penned by someone else.

Among current producers of English prose are a new group variously described as communication advisers or impression managers for large organisations, including the Church. They are trained to use words extremely carefully so that the minimum damage is caused to the organisation they represent. I cannot say that I have made a special study of the press releases and other communications made by these experts, but most of us can recognise their style and distinctive features. One thing that is abundantly clear is that no ordinary human being ever uses ‘communication speak’ in everyday language. It often comes over as insincere and even meaningless. To take one recent example, we have the House of Bishops responding to the IICSA written report. The Bishops, or rather the anonymous press release writer, came up with the tired cliché, ‘deep cultural change’. This expression was used alongside other over-used words like regret, learning lessons and shame.

For the bishops to speak about deep cultural change without telling us what this means in practice shows a gross absence of meaningful communication. To use words in this way suggests that the bishops are ready to hide behind fine-sounding words in order to try and manage their image. Tired expressions and over-used words fail lamentably to achieve this. The only people who seem to be doing their job well are the communication/press release writers themselves. They have done what they are paid to do, produce something that can quoted safely by the media in the attempt to mitigate the crisis of public relations that the Church, especially at the upper level, is facing.

Thankfully the reputation of the House of Bishops is not being wholly judged by the anodyne statements of press officers and the like. Some of the bishops have broken rank, or so it would seem, to use words that actually mean something. We have already examined the remarkable words of the Bishop of Bristol and we would claim that her words have never been near a communications officer. The past week has seen further twitter comments from the Bishop of Burnley and the Bishop of Worcester. Both of these statements sound like words from real breathing human beings rather the dry product of a communication machine.

‘It’s about the whole church and about today. There are numerous aspects of our common life that are going to require deep-seated reform’.These are the words from the Bishop of Burnley and he writes as though he means what he is saying. Absent are the sentiments of ‘learning lessons’ and ‘working for change’ which is regularly trotted out in the official statements. ‘Deep seated reform’ is potentially a radical idea and, if pursued to its logical end, will involve an enormous amount of work, discomfort and sacrifice on the part of the Church. Will the House of Bishops listen to these sentiments of its individual members, the cry of solidarity with survivors by Bishop Viv and now a recognition of the need for radical change by the Bishop of Burnley?

Our final prophetic voice from the House of Bishops has given rise to some much-quoted words from John Inge, the Bishop of Worcester. As someone who suffered at the hands of Peter Ball he knows what he is talking about when it comes to sorting out the past. His description of the way that the Church had covered up the behaviour of Ball had left a ‘stain’ on the Church. This is again not a turn of phrase that was written by a communications expert but rather implies, with the Bishop of Burley, that some deep reform is required.

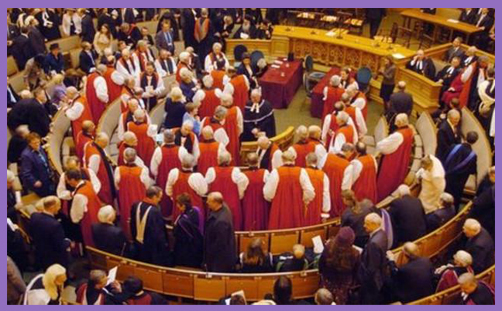

The meetings of the House of Bishops are always private occasions and only official statements (written by comms people) are released to the public. The three recent expressions of feeling expressed by individual members of this body which have not been through this filter, suggests that the meeting may have been far more interesting than we can know. Might we not speculate that the bishops are themselves divided in the way they would want to respond to the biggest public relations disaster for the Church, the IICSA report, that has ever appeared? The language of public relations experts will not be able to undo the damage that has been inflicted on the Church. As one of the consumers of this output, I would want to say that every time the Church issues statements trying to bury the past with the techniques of public relations methods, it further lowers itself in the estimation of ordinary people. Am I the only person wanting to scream every time I hear the expression ‘learning lessons’? This is not the language of compassionate human beings. That is the very least we expect from our bishops, to be people of compassion. ‘I am among you as one who serves’ are the words of the master we try to follow. Let us hear more clearly the words of Jesus in what the church says in its time of real crisis.

The problem is that “reading between the lines” – which is really what source criticism is, tends to have the same result – an interpretation that says more about the critic than it does about the source.

Regarding literary critics. In the Essay “Fernseed and Elephants” by eminent Prof of literary criticism – CS Lewis – the author has little time for literary critical attempts to deconstruct biblical texts. So please don’t represent literary criticism as the only way to read scripture. I am not denigrating them so much as saying – they represent A view, one that is commonly challenged today.

I really don’t think your connection works. For me it is profoundly unhelpful.

I agree this looks like a whitewash, but let’s not shoot the messenger (the comms person). But do lets challenge obfuscation and whitewashing…..

I really do hope the CofE is not getting into this post-truth stuff!!

I cry Amen to your closing sentence. But I’m not really understanding your objection to the examples Stephen chose. Surely we should read almost anything other than a novel with understanding about the author’s background, age, era and so on? And that will sometimes alter our view. Having two parallel creation stories, which the editors, interestingly, made no attempt to smooth over, makes the reading of Genesis so much easier. As to the Bishops, John Inge has a fine reputation as a decent and honest man. But isn’t Burnley the one who thinks women are only good for making babies and scones? I’m afraid I have a real problem with that. I’d have a hard time paying any attention to anything he said.

You do a disservice to Philip North, Bishop of Burnley. Although he does not agree with women’s ordination – a stance with which disagree – he has gained an impressive reputation and is supportive of women in ministry.

He is only supportive of women’s ministry up to a point. As a leading member of FIF and the Society he is working against women in the priesthood and episcopacy.

However, I do respect him for his excellent work in reminding the Church of our obligation to the poor, and our neglect of estate ministry and other under-resourced areas.

I agree with your comments about source criticism in biblical studies. That approach was long out of fashion in literary criticism when I did my Eng. Lit. degree in the 1970s; I was bemused to find it still in use when I di day theological training 10 years later. Frustrated, too – in my view it’s like sitting down to a banquet and neglecting the food to obsess about the make of the china.

Socio-historical study of the background to the text, on the other hand, can be very illuminating, as Athena says.

Re. Stephen’s main point about bishops’ statements, however, I’m in agreement with him. Those anodyne, over-processed statements really don’t serve well, and when bishops speak from the heart it’s most refreshing. I’d guess the bishops are terrified of giving a hostage to fortune when they speak, and that’s why they rely on comms. There have been occasions in my own ministry when I’ve had a comms. statement up my sleeve in case it was needed, but I’ve usually tried to adapt it a little to my own more natural way of speaking.

With bishops, the group-speak isn’t only when they’re potentially in bother, as with the IICSA statement. On a theological website I once asked if anyone could explain to me what the phrase ‘God in Christ’ means (as for instance, ‘forgiveness is available to us through God in Christ’). Turned out it didn’t mean much to anyone; it just seems to be a sort of verbal signal that the speaker is a bishop.

Fashions come and go, I agree. Nevertheless I have gained a lot from source criticism; in particular it has helped me understand the role and motivation of the final editor. I have explained what I mean by role and motivation in my earlier comment on Hebrews.

I wouldn’t agree that there is necessarily an editor, in the way we understand the role.

The earliest books of the Bible will have started life as stories told by the fireside and passed down through many generations. In non-literary cultures people have excellent memories (which tend to deteriorate when things start being written down) and are usually scrupulously careful not to alter the tale they’ve learned. The Jewish scholar Jonathan Magonet is interesting on this. The person/s who did finally write down these narratives will have inherited the tradition of accurate recall and likewise been careful not to alter them – even to the extent of preserving inconsistencies in the text.

I can’t recall your comments on Hebrews, but to me the text bears all the hallmarks of having been written by a single author. It’s very closely reasoned and the line of argument is maintained over multiple chapters. Interestingly, there is a theory that the author was Priscilla. Certainly she fits the profile of a learned Hellenic Jew converted to Christianity, and we know St. Paul had high respect for her teaching abilities; he rated her before her husband. It might also explain why, uniquely in the New Testament, the author’s name is not given. In those days and that culture, it wold be no advantage for a learned work to carry a woman’s name. Leaving it off would gain a wider readership.

I agree with your line of argument. Certainly Hebrews reads like a single piece of original writing. What my earlier comment focused on was the creativity of that author. The use s/he makes of the references to Melchizedek is highly creative, well beyond what could have been meant by those texts in their original contexts. If the text (Hebrews) is regarded as (unquestionable) “divine revelation” we miss that very creativity and the sense of the impelling experiences which motivated it.

Yes, if we think ‘revelation’ means ‘dictation’. But it might mean – and I take it to mean – that the Holy Spirit inspired people with the creativity to write. The same Spirit might easily inspire new connections.

Thanks Janet. I feel I should reply to your final comment with a rofl emoji! As for +Burnley, I don’t know him and have never met him. But I have met a lot of men who arrogate all the interesting/high status/well paid unto themselves, and the low status/uninteresting jobs to women. And a lot of men who speak to me as if I am a primary school class. Maybe +Philip absolutely never does that. Good, if not, but I’d always be on the edge of my seat I’m afraid.

Sorry about missing word!

Although a lot of these statements will have originated in a comms office, I am fairly certain they will also have been tweaked by various lawyers and possibly insurers as well. Crafted statements are just that and no one individual would usually be ‘brave’ enough to sign off on it.

Dick, thanks for your helpful first two paragraphs, which I agree with.

Dame Helen Gardner wrote in 1951, “Trying to find sources in literature is like trying to weave ropes in sand”. Nice.

Thanks Janet.

Regarding the supposed oral tradition of OT texts, I discovered a fascinating thing. In Hebrew, “David” (DWD, consonants only, remember) looks very like “Dor” (DWR) which means ‘generation’. This is because Hebrew Ds and Rs are very similar to look at.

DWR is scattered throughout the OT except in the books where David is mentioned, and there its use is conspicuously absent. Alternative phrases to ‘in every generation’ are used instead, e.g. ‘for ever’.

I presume this was done to avoid possible visual confusion when looking at the text. Having David and Dor together could have confused readers.

What this suggests is that the look of the final text had an influence on its wording as well as any supposed aural tradition. It’s good to remember that talk of the stories originating round campfires, although widespread in biblical studies, is pure guess work. We have no evidence for such gatherings.

It’s a reminder of how careful we have to be when looking at an ancient text. It is so easy to add our assumptions.

Fun!

Thanks for the DWR/DOR thing, that’s fascinating. I wasn’t suggesting that all of the Bible began as oral tradition, just the earliest parts. Records of the kings, including David, would almost certainly have been written down. The kings would make sure of that!

Of course the narratives of oral tradition may not have been swapped round campfires, it may have happened in some other context., such as while resting during the heat of the day. I was reading this week that recent research indicates hunter-gatherers (such as the earliest Homo sapiens) would have had quite a bit of leisure time. It would certainly make sense to use some of this passing down traditions to the younger members of a family/group. Illiterate peoples still do this.

I enjoyed your last two articles. Working in a fundamental church it was a breath of fresh air to read them. The quote ‘ in my father’s house are many mansions’ is changed to ‘rooms’ I would love to know what it is more likely to be in the Greek or Hebrew scripts. I love mansions of course!

“Mansio”, I think. Meaning motorway services, more or less.

New perspective, thank you.

And regarding oral tradition – this is not “ancients round camp fires” only! I have done a little work on the use of oral communication in cultures from an anthropological point of view. There are many contemporary cultures that still use recognisable oral traditions.

Stories, songs, poems, proverbs – these are all oral forms. And though the gaelic word ceilidh now is taken to mean a dance party – in the Outer Hebrides, in the gaelic culture (particularly in the rural villages) a ceilidh can still mean a gathering in the kitchen to swap songs, poems, & stories. Oral forms are very important. In an oral culture – “when an old person dies, a library dies with them”.

Fascinating subject. And don’t forget dance. Polynesian culture has teaching dances. Like the girl dressed in white who dances backwards, because fairy terns fly backwards, and they were the sign that land was close.

That’s interesting. A friend of mine was researching Bp. Stephen Neill in India, and said elderly men and women would walk for days to meet her. Then they would chant their memories to her so she could record them. Being non-literate, that was the way they remembered such narratives, they put them into a chant.

I wonder if that’s how some of the Old Testament started. I don’t know Hebrew, but some of it seems to have a rhythm. And there was evening and there was morning, the first day…And there was evening and there was morning, the second day….

That’s fascinating.

My sister collects oral history from the descendants of settlers of America’s west. She also works with native Americans, as does my nephew. She’s a great believer in oral tradition.

Alan Garner, in ‘The Legend of Alderley Edge’, tells how a legend handed down through his family, combined with some archaeology and local geography, told of the days when there was pagan worship in the Macclesfield area. As in other oral traditions, the legend was passed down nearly word for word.

What fun. Here’s another interest of mine: seemingly unconnected passages placed together. E.G. Genesis 38 which appears to interrupt the Joseph story. I enjoy looking for possible connections between the two.

So here’s a small challenge for you: in Genesis 18 what connection is there between the meeting of the angels with Sarah and God’s discussion with Abraham about Sodom later in the chapter? Answer in a week…

The connection between Gen. 38, the story of Judah, and the Joseph narrative is that they were full brothers – both sons of Rachel. The other brothers were the sons of Leah. Judah plays an important part later on, being the one Joseph insists is left as hostage while the others go back to Jacob. Perhaps these narratives came from the tribes of Joseph and Judah? Certainly the accounts of Joseph’s time in Egypt would have to come from Joseph himself, perhaps with the help of his family for the later portions. Given Joseph’s senior position in Pharaoh’s household he may have been literate, and may also have ensured that his sons were.

Judah was the royal tribe, producing kings (and, eventually, Jesus).

The connection between Gen. 38, the story of Judah, and the Joseph narrative is that they were full brothers – both sons of Rachel. The other brothers were the sons of Leah. Judah plays an important part later on, being the one Joseph insists is left as hostage while the others go back to Jacob. Perhaps these narratives came from the tribes of Joseph and Judah? Certainly the accounts of Joseph’s time in Egypt would have to come from Joseph himself, perhaps with the help of his family for the later portions. Given Joseph’s senior position in Pharaoh’s household he may have been literate, and may also have ensured that his sons were.

Judah was the royal tribe, producing kings (and, eventually, Jesus).