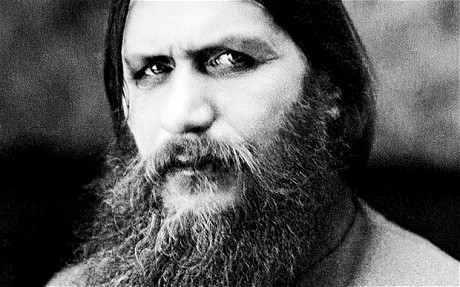

Everyone has their fifteen minutes of fame said Woody Allen. My fifteen minutes beckoned some eighteen years ago and then vanished as quickly as they had appeared. My brief flirtation with fame was when I was asked to take part in an independent television programme about Rasputin. At one point there was even a suggestion that I might go to Russia and do some commentary from there about Rasputin’s life. This was then downgraded to being a ‘talking head’ role in a UK studio, but the footage which was shot with my commentary was eventually completely edited out in favour of other material.

The only thing left behind from this brief flurry of excitement was the reading I did, to prepare for the programme. I wanted to sound reasonably informed on Rasputin’s notorious but very significant part in Russian history. I had just seen my book of religion and power, Ungodly Fear, published and so I was then well sensitised to the way that Rasputin could and did use the image of holiness to seduce the entire Russian royal family in his bid for power. There are in few people in history who succeeded in exercising so much power, personal and political, all at the same time. His voracious appetite for sex, partying and political power seem to have had no limits. No one seemed prepared or able to stand up to him until he was murdered in 1916 by political rivals.

The part of the story that I found most intriguing was Rasputin’s relationship with the Czarina Alexandra. She was instrumental in keeping Rasputin right at the heart of the royal family during those dying days of the Romanoff dynasty. It was not only because Rasputin seemed to be able to help her haemophiliac son that the relationship was strong. There seemed to be something far more than that which kept this destructive relationship alive for so long. As I read around the life of the Czarina it was evident that she came to Russia in 1894 to marry Nicholas as, what we would call nowadays, a ‘vulnerable adult’. Her mother, Princess Alice, one of Queen Victoria’s children, had died when Alexandra was only six. Life in a German castle as the motherless daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse cannot have been easy. Her mother seems to have taught her to speak English and presumably she would have learnt fluent German. Arriving in Russia she would have had few opportunities to speak German. Czar Nicholas was, however, fluent in English and this remained the language they used to communicate with each other for the whole of their married life. The nobility and the Russian court had, I believe, a preference for French. Russian was the language spoken by the common people.

Rasputin served to meet several of Alexandra’s needs. First, he was a gateway for helping her feel that she was making contact with the unknown people outside the court, especially the country people, the peasant class. Further, although Rasputin was not a monk, he represented for the Czarina the mysterious aspects of the Russian religious soul. Associating with him enabled her to feel better connected to her adoptive country, the real Russia beyond the palace walls. A further reason to feel deeply linked to Rasputin was in the way that he tapped into her extreme vulnerability. Her father had died two years before her marriage in 1892. We can speculate that she still needed parental support which her emotionally stunted husband was not apparently able to provide. Psychologically she came to be more and more dependent on Rasputin. She had been swept up into a relationship of deep intensity, drawing on the sexual energy of both parties, though apparently without physical consummation.

The power of Rasputin over the Czarina was thus an all-embracing one. It tapped into Alexandra’s need for parental and human affection as well as guidance in a strange alien world. The nature of Rasputin’s personality and his enormous charismatic and sexual energy fed and alleviated areas of Alexandra’s neediness at a profound level. To describe this relationship using words like seduction or charm is inadequate but such words hint at the way the relationship with Rasputin seems to have combined charisma, sexual energy and religious fervour together.

Since preparing to take part in that programme, my understanding and study of ‘charisma’ has moved on a great deal. In particular I have come to see that it is normally linked with narcissistic traits. No doubt if I were asked to comment on Rasputin again, I would draw attention to the way that he fulfilled most of the criteria for that disorder. The one area that I have not made any further progress in understanding is the way sexual energy and charisma seem often to be linked. When we describe the power of charisma in an individual whether in a religious or non-religious setting, we often want to describe it in quasi-sexual terms. People who exercise this kind of power have a kind of magical charm which seduces people into their orbit. We talk about people being in some way being bewitched into a relationship. Even though I cannot make a completely coherent pattern out of these observations, there are connections between these ideas that I feel are worthy of further exploration.

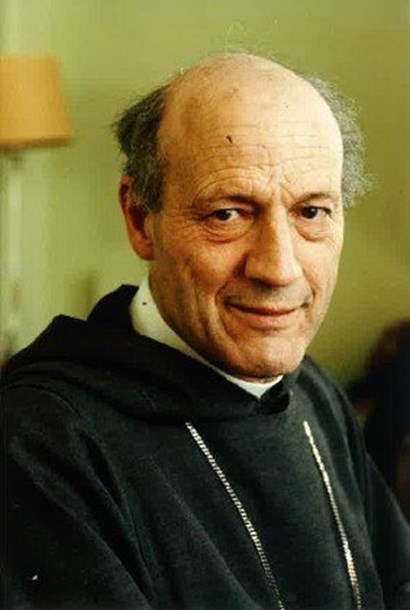

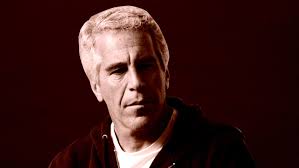

Two other recent stories cry out to be compared with the Czarina’s tale in recent history. They both involve royals and they both involve relationships involving charisma and the use of sexually-charged power. Two people, Peter Ball and Geoffrey Epstein, successfully used their charisma and charm to manipulate members of another Royal Family in pursuit of the perpetrators’ own selfish ends. Ball needed the friendship with Charles to protect his establishment credentials after his police caution. Epstein, according to some interpretations, was exploiting a faux friendship with Andrew to provide cover for his nefarious activities. In neither case, of course, was sex used directly, but there seems to have been in each ‘friendship’ a magnetic irresistible power drawing in the royal victims. I have personally witnessed the charm/charisma of Peter Ball when he was my diocesan bishop. It is in retrospect that I can identify a powerful attraction which was not unlike a form of seduction. A child might use the word ‘creepy’ to describe this uncomfortable combination of repulsion and attraction at the same time. I know nothing about the way Epstein came over to the people he manipulated (I am not here talking of his female slaves). It is not unreasonable to suggest that he was gifted in this area of charming powerful people and making them do his bidding with the use of the tools of a sexually charged charisma.

My reader will see that I am not in a position to offer a coherent pattern about the way the dynamics of charm, charisma and seduction can be described. I am describing something based on hunch and instinct rather than scientific analysis. And yet I am sufficiently confident that I am describing something worthy of our attention that I want to write about it in this post. The sooner we can unravel these strands of human behaviour, the better we will be to make sense of many scenarios that take place within some dark areas of church life. To understand is to be able to prevent something bad in the future. That is surely a worthy aim even if our tools of analysis are not yet complete.

My experience is when a person, church, or situation seems too good to be true, it may well be. While it’s not good to be suspicious of every bit of goodness and kindness to come along, if someone is really charismatic, it’s time for caution That’s particularly the case if you see odd behaviors that are hostile or combative. Pay attention to those, as that sort of subtle thing is a sign of narcissism.

Don’t you think that many people are attracted to the vicar or the curate anyway? If you add in the effects you describe, it becomes very powerful.

An interesting common link with all these different people – aside from their gender – is their appeal to the aristocracy of their day. They seem very able to read and play into the need of the rich and entitled to be flattered and made to feel even more special than they think they are. The ability to exploit situations for their own ends marks each of these people. Ingratiating themselves with the rich and powerful gives a veneer of respectability to carry on working outside of the law. They will reward the rich while abusing the poor and the vulnerable. It was interesting to hear the justifications given in the Panorama interview for remaining in contact with the weird, abusive world of Epstein – it opened doors, provided free lodging, was convenient and in the end was all to do with a misplaced sense of honour. The damaged women were not worth a mention because it is all about male privilege and power over people and situations. It was interesting also to note how hard it was for both Charles and Andrew to acknowledge the people they knew were convicted abusers. Self preservation, distancing and denial seemed the main priority. The #metoo movement has a long way to go. Establishments still refuse to be honest and real. The refusal of the Russian aristocracy to let Rasputin go played a significant part in their downfall. By the time their own class turned on Rasputin the damage was done. Sooner or later reality bites, the powerless rebel and enough is enough.

I think it’s fair to say that everyone finds it hard to face the truth at first if a friend turns out to be a wrong ‘un. Not just about sexual misdemeanours, either. If someone you know and like turns out to have been smuggling cigarettes, or using drugs, or embezzling, the first reaction is always disbelief. The first thing is not to accuse the person who’s telling you of dishonesty. They may be a victim. The second is to let the truth in. As the facts start to become clear, you need to be prepared to change your mind. Even if you’re not a public school boy with that sense of entitlement, that’s hard.