I do not know whether anyone reads the books by Adrian Plass anymore. They are full of trenchant and perceptive comments about the church culture Plass was part of in the 80s. There is one memorable passage in his Sacred Diary when he is speaking about the experience of being in a Bible study in his conservative charismatic church. He describes how the passage for the week was read, and then all eyes were then turned to the leader, ’to find out what we think’. Clearly there was an experience of bonding and merger in relation to worship. That somehow was expected to be transferred into the way that individual thinking by members of the congregation was practised.

Church membership does indeed flourish when it successfully gives to people a sense of belonging and a place within the group. Nevertheless, such belonging does not have to involve everyone thinking the same ‘correct’ thoughts as in Plass’ church. Churches, both locally and nationally, can be said to be ‘bodies’ of which we are part. When churches get this right, we find that members all receive a level of spiritual and emotional integration with others, which is life enhancing. The metaphor of the Church as the Body of Christ is also one that is richly evocative and potentially the subject of numerous sermons. I introduce this idea of belonging and the metaphor of the body as a prelude to pointing out how, in some circumstances, this kind of experience can and does go wrong. As an idea it needs to be approached with a certain caution. In the first place when we join a group, we must become aware of the way that this membership will impact on what we think and say. There is of course nothing wrong in being part of a group consensus. Nevertheless, I would suggest that it is always important to be alert to the possibility that opinions are being formed by something we call ‘groupthink’. This expression, which has been extensively studied over the past 60 years in social psychology circles, is a way of saying that when a group of people have identical ideas, there may be an unconscious merging process taking place. This will often be unhealthy. In some contexts, such as in the military, it can be a potential cause of disaster. To prevent such a potential catastrophe happening in this kind of situation the outsider, the dissenting opinion, must be given a voice and honoured for expressing it.

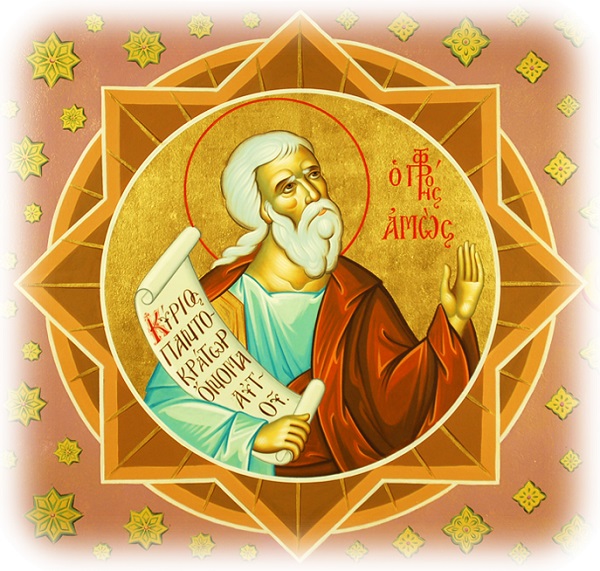

The Christian tradition has had a lot to say about outsiders and Jesus himself is described as the one who ‘went outside the gate’ to bring alienated sinful humanity back into the presence of God. We also are encouraged to go to him ‘outside the camp, bearing the stigma that he bore’. In life and death Jesus identified with outsiders, the sinners and riff-raff of his day. But there is an earlier outsider in scripture that I want to focus on in this piece. Janet Fife mentioned the OT prophets in a blog comment a few days ago. The outsider prophet that especially comes to mind is the figure of Amos. He is the classic dissenter and he stood outside social and religious norms simultaneously. ‘I am no prophet nor a prophet’s son’. His outside status was also confirmed by the fact he was a foreigner, (a Judaean in Israelite territory) and he was called to the menial task of a shepherd and ‘dresser of sycamore trees’. Amos’ prophecies, directed against the northern kingdom of Israel and uttered around 720s BC, were devastating. He saw little that would be left after a terrible destructive military incursion. The details of Amos’ prophecies are not important here, but simply the fact that they exist. Here we have a solitary figure, an outsider, a foreigner and an unqualified person speaking truth to an entire nation about what God had determined. That nation did not listen and it was destroyed.

I do not think that we currently have a single Amos speaking to the Church of today. We may, however, have the voice of Amos fragmented across the witness of many dissenting outsiders who have something to say to the church. Institutions, whether entire countries or church bodies must learn to hear the prophetic voices spoken to them through the mouths of these outsiders. Why might the outsider, the dissenting voice, have something important to say which is not being expressed within the group? I am far from claiming that the outsider is always right or that institutions cannot speak truth to themselves. What I am suggesting is that the ‘groupthink’ principle warns us that no institution can afford to shut out the outside and independent voice. That opinion or insight is not to be blocked off. Indeed, anyone who expresses an opinion which is not reflective of a group norm is at least likely to be worth listening to.

In this reflection I cannot help but think that, in the world of safeguarding, the prophets are easy to identify. These outsiders, the ones who see things clearly by being free of the encumbrance of institutional interests and values, are the group we collectively call survivors. Survivors speak truth to power. They have passed through the crucible of abuse. Whether or not they remain loyal to the institution that was involved in their abuse, they still have valuable insights and a critical understanding of it. Janet pointed out that the other outsiders will include such groups as the BAME and the LGBT communities. They also will see things differently because of their long experience of exclusion.

In the post-Covid days that lie ahead of us, church leaders are going to have to do, among other things, an enormous amount of listening to ensure that their institution will still be fit for purpose in the future. Whether in the realm of safeguarding, which is at the heart of this blog’s concerns, or addressing some other focus, we can hope that the church will be able to hear what is being said by others who may not be members. The word of the outsider, the critic even, may be the word of God to this generation of church leaders and our own House of Bishops. Survivors of abuse, possessing an enormous wealth of experience and understanding of what is involved in this area, have a vast quantity of useful things to say about the right way forward. They should not be consulted as a kind of public relations exercise, but all their words should be carefully listened and pondered in case, like Amos, they are speaking the prophetic words and will of God. Ignoring their witness would be both foolish as well as expensive for the church.

The prophet, the outsider, is one who utters the words of God to the institution, even though that word may be uncomfortable or even disturbing. To compare the state of the Kingdom of Israel in 720 BC and the Church of England in 2020 may seem a little far fetched. But, in both situations, there are real serious threats which are sufficiently serious for me to suggest that such parallels do exist. Church leaders today must listen, not only to its internal groupthink, but also to its minorities, the survivors, the BAME community and others who seem to have received the Good News, but struggle to be heard by the rest of the church. It is both hearing and responding to the prophetic word of God that that the church may find a new impetus and power to take it into the future.

I reread The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass a couple of years ago, and it struck me how little it’s dated. Interestingly, the ‘prophets’ in the book are also outsiders – Frank and the monk. (I’m convinced that the monk was based on Peter Ball, who was Bishop of Lewes at the time the book was written and had quite a following among charismatics in the area; but that’s a different story.)

Alarm bells always ring for me when a theological college appoints one of it own alumni to the staff, especially if their time at the college was recent. They also ring when a priest is appointed an archdeacon within the same diocese; or an archdeacon a bishop. These insider appointments promote groupthink. And they’re much more common now than they were when I joined the Church of England in 1980 – an unhealthy sign of an inward-looking church.

*giggle*. Must be noisy in your head Janet! Happens all the time. I’ve twice seen retiring incumbents move house to live in their “old” parish and take up posts such as rural dean, or diocesan spokesperson. Suffragan bishops becoming Diocesans, rectors becoming archdeacon. Sure, all the time.

Yes, it does happen all the time. And it’s a sign of an inward-looking and unhealthy church.

Did you see the articles about ordinand Augustine Ihm being turned down for a curacy on the grounds that the parish is ‘monochrome white working class and you may feel uncomfortable?’ Ihm is in fact an Afro-American who was adopted into a white working class family, but the assumption behind that infamous letter of rejection is that only lookalikes are acceptable.

But we are always being called to ‘come to Jesus outside the camp’. We follow a man who was despised and rejected, and who carries outsiders close to his heart.

Yes, I saw that. Not bothering to read the file. The late David Adam was once told he wouldn’t fit in as he had no experience of “real life”. (I paraphrase). He used to be a miner!

I was once interviewed to be chaplain and fellow of a Durham college, a post which involved researching a PhD. I was passed over in favour of a young man. When I asked why I was told that they thought he would be better at combining academic research with a part time job. I’d researched my MPhil while working full-time, while he did his MA full time, so that clearly didn’t wash. I think the fact that my rival had a double barrelled name and was a graduate of the same college were the real factors. Class and insiders again.

Mind you, it happened to me in secular life, too!

This is a particularly fine piece of writing by Stephen Parsons. His ongoing work here has facilitated a collective prophetic voice into the vagaries of church life.

A point to emphasise here is the power of a dissenting outside message to enable improvement. If you don’t think the church you lead needs to improve, you’ve got a problem. If you only appoint and listen to your cronies, the trajectory you take, even if only slightly of course, will be way off in no time at all.

The dissenting voice, even if you don’t think it’s prophetic at all, is data. Check it out. The church leaders of Christ’s day ended up putting Him to death rather than listening and changing.

Sure some voices may be chaff, but don’t miss the wheat.

Dissent is vital in science too. Ignoring uncomfortable data is partly responsible for the covid mess IMO. See here: https://ramblingrector.me/2020/06/10/experts-and-skeptics/

Richard Feynman, Nobel prizewinning physicist, said: “There is no harm in doubt and skepticism, for it is through these that new discoveries are made;” and “Science is organized skepticism of the reliability of expert opinion.” Not just science.