One of the permanent psychological legacies that many survivors of abuse have to carry is the possibility of being ‘triggered’ at any moment. This is a kind of mental explosion which takes place when a past abusive event is reactivated by something seen or heard. The mental shock involved in such a triggering can, in some cases, produce tears, shaking or other physical signs of distress and despair. Most therapists who seek to help survivors are familiar with these symptoms. It does not make them easy to deal with. They are never trivial or routine. Triggering is a source of real pain and anguish for sufferers and it is possibly life-long for those who are afflicted by it

Recently on Youtube, a section of film, potentially triggering for survivors, appeared, which featured John Smyth, the notorious abuser. He was speaking from South Africa about a notorious legal case there, the trial of the Paralympic athlete, Oscar Pistorius. I watched it with a grim fascination so that I could get some feel for the man, his body language and the tone of his voice. Hitherto I had only seen the muttered comments he had made in the fleeting Channel 4 interview with Cathy Newman in February 2017. The date of this other interview, 2014, was at a time when Smyth was apparently able to make frequent trips to the UK from South Africa. His evident confident carefree pose also could have contributed to a potential triggering effect for any of his victims. The significance of the date when it was made will become apparent as we go further into reviewing some other episodes in the more recent story of Smyth.

The outline of Smyth’s story is well known to readers of this blog. His crimes of religiously inspired acts of violence against a group of boys and young men go back to the late 70s and early 80s. These were linked to his position as Chair of the Iwerne Trust, a charity now called Titus Trust. The Trust changed its name in an apparent attempt to distance itself from any involvement with Smyth and his crimes. Both charities were/are under the influence, if not the control, of the REFORM/Church Society network and their leaders. They were set up to inculcate a cadre of privileged public-school boys with the culture and beliefs of the strand of conservative evangelicalism favoured by the network. In general terms, what is now called the ReNew constituency upholds a style of evangelicalism which stands apart from the more widespread variant favoured in charismatic circles. It has favoured a patriarchal style of leadership which avoids granting women positions of real responsibility. Although the ReNew strand of teaching and practice in the Church of England is not widespread, it does have considerable influence and access to wealth and power. When the crimes of Smyth first became known to the leaders of this network in the early 80s, there were powerful individuals on hand with the necessary financial clout to ship Smyth out of the country to Africa and support him financially until his death in 2018.

The recent story of John Smyth begins in 2012. In that year two things happened. The first was a newspaper column written by Anne Atkins in the Mail on Sunday, when she described the bare outlines of the Smyth story without giving his name. Anne referred to this column when she appeared on Cathy Newman’s ground-breaking Channel 4 report in February 2017. First she admitted that the unnamed Christian leader who was guilty of beating boys was indeed John Smyth. What was more interesting was the way that Anne recalled the consequences of revealing this information to the Mail on Sunday readers. To quote her words in the 2017 interview, she told us that ‘the flak I received after the article was horrible actually ……(it came) from people who were senior to me. Why are you stirring all this up?’ These few words are fairly revelatory. It implies that Anne was got at by people who knew all about the Smyth story, but they were also senior to her. By implication, these were the leaders in the Titus/REFORM network at that time. The words she used tell us that the attacks were plural. Some emanated from leaders; others possibly from rank and file members of the network like herself. All who attacked her seemed to know the full Smyth story and were upset that the dam of secrecy and concealment was being breached.

The Mail on Sunday article in 2012 was the first crack in the great Smyth cover-up. The second event was the beginning of a correspondence between a Smyth survivor and a senior member of the Iwerne/REFORM network. The survivor, who calls himself Graham has kindly shared with me the chronology of his own personal attempt to bring the events in a Winchester garden shed to the attention of the Trustees of the Iwerne camps and also the wider church. The correspondence that Graham initiated in March 2012 was seeking, in the first place, access to psychiatric help It. continued over 2012 and the first half of 2013. In July 2013 Graham is finally passed on to the safeguarding team of the Ely diocese. In Graham’s words, he hoped some well-oiled process would swing into action and the end result would be an offer to find and pay for psychiatric or counselling support.

The details of the correspondence by Graham with Ely reveal his heightening of frustration and anger. One issue that caused Graham considerable grief was finding that his name had been shared by the Ely DSA with the Titus Trustees, ignoring his desire not to be named. Much of the correspondence is about finding suitable therapy and support. The money that was found came from private sources via the Titus Trustees, but it ran out in April 2015, having lasted for barely a year.

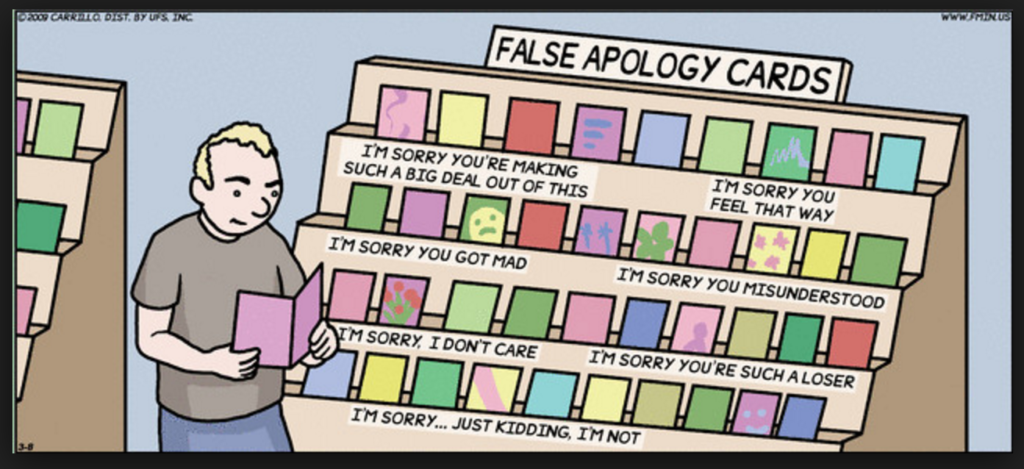

The other preoccupation of Graham was his attempt to alert the Church authorities to the continuing threat of Smyth himself, even though he was no longer living in Britain. The Bishop of Ely wrote to the Archbishop of Cape Town to tell him, in some detail, the issues around Smyth. The letter I have seen made it easy to find him by enclosing his current South African address. The idea that Smyth was uncontactable was patently absurd since he was an active figure in South African legal circles, working for the Justice Alliance of South Africa. The Bishop of Ely received no replies and in May 2015 the DSA wrote to Graham to say that he ‘had no power to compel agencies in South Africa to respond to my concerns.’ This somewhat feeble response was the best that Ely could come up with in spite of seven letters from Graham between May 2014 and August 2015 to get the Church to take the whole issue seriously. The Titus Trust, although they knew that Smyth was entering Britain regularly on visits, refused to accept that they had any moral or legal obligations over his behaviour. From that point until the Channel 4 programme in Feb 2017, the story was like a ‘pass the parcel’ game. Nobody wanted to accept responsibility for enquiring too deeply into the abusive legacy of this man or the danger that he potentially posed for the church in the future. Smyth, as is well known, died in Africa in mid-2018.

The story ends with no satisfactory conclusion. But we have to ask what might have been done to help Graham and the other victims and to bring Smyth to some form of justice. The key person who seems missing in action is of course Justin Welby. No one claims that Welby knew anything prior to 1982 and what he knew after that was merely that Smyth had been uncovered for unspecified misbehaviour and banished. But he certainly did know him personally and many in the network of people that Anne Atkins refers to in the Channel 4 interview. Welby definitely heard about the Smyth affair in the autumn of 2013, possibly a year earlier. This was around the same time as a group of ‘senior’ church people in the REFORM network were giving Atkins ‘flak’. If Welby knew nothing before autumn 2013, he certainly knew lots of the people who could have brought him quickly up to speed over the Smyth affair. All the evidence (anecdotally supported by Atkins) points to the detailed story having been shared among many individuals in the REFORM network. This had been the crucible and setting for Welby’s own Christian conversion while at Cambridge in the 70s. Was Welby not even curious to find out the full story, when the name Smyth was first mentioned in 2013 in a safeguarding context? If Welby had leapt to and written formally to the Archbishop of Capetown in consultation with the Bishop of Ely, that dreadful ‘triggering’ interview might never have been able to take place. The civil authorities in both South Africa and Britain might have been alerted to do their work much earlier. What-if scenarios are seldom profitable speculations, but there seems to have been a failure to act with energy and alacrity and allow a safeguarding catastrophe which is still reverberating within the Church. The Makin report is unlikely to resolve all the issues over the Smyth affair. Indeed, it will once again reveal ‘shoddy and shambolic’ practice at the heart of the Church of England.