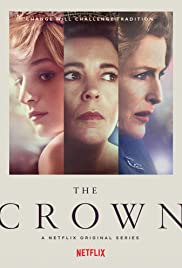

There was an interesting story in the paper today (Sunday) discussing the impact of the programme, The Crown. Apparently there has been a survey of public opinion about attitudes of the British general public towards the Royal Family among those who have seen this series. Although, for the purposes of a good fictional story line, the Crown showed the Royal family sometimes in a poor light, public attitudes towards them have not been changed in a negative direction. It was thought that the portrayal of an adulterous Prince of Wales might cause damage to his reputation. In fact, the opposite seems to be true. Overall, 35% of those watching the series had begun to see the Royal Family in a better light. Only 5% had allowed the programme to make them think of the family less favourably. It seems that institutions like the Royals can survive criticism, if those looking on feel that they have been allowed a better view of what is going on behind the curtain. Many human frailties can be forgiven and tolerated, when the observers feels that he/she is being given something like a frank disclosure. The Crown may be to a large extent a fictional reconstruction, but it has given the viewer a sense of understanding the human foibles of this privileged group of people. Most behaviour, short of actual criminality, will be forgiven by most people. The more we feel we understand, the greater seems our capacity to forgive.

As I thought about public attitudes towards a major institution in our society, like the Royal Family, I compared it in my mind to another story that appeared in the Church Times on Friday. This published the results of the MORI Veracity Index for 2020. This poll asked the man or woman in the street which professional person was most likely to tell the truth. The rate for those expecting truthfulness from the clergy has apparently fallen to a mere 54%. This score has fallen by 9 points in the last year alone and by 29 percentage points since 1983. We can only speculate about the reasons for this spectacular collapse of trust. It is likely to have had something to do with the endless cycle of scandals over the abuse of children in the past ten years. But, whatever the reason, the current situation appears to be reaching a point where many clergy will no longer feel comfortable wearing clerical attire in a public place. That indeed, may already have happened in some places. If true, it a sad reflection for the Church that attitudes have now become so negative. Whatever the reason, it is tragic reality that clergy are being placed in a zone of being thought unreliable and possibly untrustworthy.

These two surveys need to be held alongside one another because there are some further lessons to be extracted. Two solid British institutions are revealed to be beset by human frailty and failure. In one case public opinion towards them is in the process of recovery with an increase of affection and esteem. In the other case, public respect appears to be on the decline. Why is there this difference? There is, I believe, a simple explanation. The attitude of people towards institutions is not especially affected by moral failing unless they belong to the most toxic categories. What matters is the way those institutions deal with the failings. Any attempt to hide, to cover-up and to pretend will be seen for what it is – hypocrisy. Here hypocrisy is pretending to uphold one standard of behaviour while all the time behaving in another. If the scandal of abuse against children and the vulnerable had really been about a few bad apples, the general public would by now have forgiven the church institution and possibly moved on. The things that have upset countless people have been the cover-ups, the handwringing and the apparent indifference of people in authority in the Church. There has been little readiness to show love and compassion for the victims/survivors. Few people have taken note of the details of the abuses, as do the readers of this blog. But the public have been left with a sense that there are many tales of unfinished business. There is always a feeling that many church people have been far too concerned to keep the show on the road than taking radical steps to help and heal the many who have been wounded or broken by this apparent epidemic of abuse. It is this sense of the Church in disarray, not knowing what to do to protect children that has been so damaging. Of course, the Church has made enormous progress in this area of safeguarding. But as the public relations experts fully recognise, it is not what the facts are in a particular situation that count; it is what impression is left after a period of negative publicity. The overall impression is negative and that is what urgently needs repair. We want a situation where the clergy can walk the streets everywhere without fear of insult.

As I was thinking about this apparent decline in the reputation of the Church of England in society, I was drawn to remember the passage in Matthew 23 about religious people and institutions being likened to whited sepulchres. This is a passage describing how, on the outside, everything may seem beautiful, but on the inside, there is filth and decomposing human remains. It is as though the general public, who used to see only fine beautiful buildings and honourable people, have been afforded a glimpse of something dark and not very wholesome through a crack in the white façade. Something rotten and corrupt is showing through the crack.

In the comments on Thinking Anglicans about the resignation of Melissa Caslake, there was a quote given. ‘Half of the leadership of the Church of England knows that it needs to change to survive, but the other half feels that survival depends on preventing change at all costs.’ The evidence suggests that if public perception of the Church is changing as fast as it is, then change becomes a life-death matter for the institution. To use the vivid picture language of Jesus, if the whited sepulchre is cracked open at one end, then all the whitewash will be ignored. The only thing visible will be the bones. The Royal Family has, metaphorically speaking, been cracked open but survived. They all seem to be (apart from Prince Andrew) on their way to recovery in people’s estimation. People it seems, can cope with frailty and failure. But they cannot accept dishonesty and hypocrisy.

Most of us have experienced the devastating effect of secrets within a family. In the past there were sometimes extra children born to a family after it seemed complete. Then, years later, it was discovered that the youngest child was in fact the daughter or son of a teenage daughter. No one was prepared to talk about the situation but the damage to the identity of the child born out of wedlock could be enormous. I am sure that most of my readers will recall some secret in their own family which caused damage because of silence. Scandal is thought to be dangerous and damaging. What is far worse is a scandal never admitted. They are like festering wounds. From a human point of view, people are far readier to cope with lapses in human behaviour than we think. Obviously, there are, even now, activities which are hard to forgive or let go. I am thinking of such crimes as gross cruelty to a child or abuse of some kind. But most of the scandals that we heard about, which thought to bring disgrace on a family, did not come into this category. Secrets when brought into the light of day normally do not seem so terrifying and will, for most people, incur understanding and forgiveness.

There is a way forward for the Church. It needs to decide on a path of openness and genuine remorse for its past failings. If it takes the other path of commissioning a new coat of whitewash every time there is a scandal, public trust and respect for the Church will continue to decline. Human beings generally respond well to a narrative which begins: ‘We got it wrong. We made terrible mistakes and we ask for your understanding and forgiveness.’ If the Church over a period of years could become the institution which is prepared, never to cover up but to own up, then perhaps people in our society would learn to trust it more. That terrible loss of trust that has been sustained over the past thirty years might be reversed. I do not see this process beginning easily, unless we have someone of real leadership quality prepared to take such change forward. We arrive back at a place which we have frequently visited. We come back to imploring the Church and its leaders to embrace integrity, truth and honesty and put away the falsity of thinking that they can continue to manipulate, through public relations techniques, the reputation of the Church as they have done over the past years.

I agree, of course, regarding the Church’s duty to be open about its failings.

I’m curious, however, about the survey. Did it measure only attitudes to the Royal Family in general, or did it also measure attitudes to individual members? Judging by some of the commentary I’ve been reading, Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall may have lost some of their popularity since the Crown’s depiction of their behaviour towards Princess Diana. And why, I wonder, are they not styled the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall, similarly to the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the Duke and Duchess of Sussex?

Prince Charles is the Prince of Wales and Heir to the Throne. His wife, the Duchess, is technically the Princess of Wales but chooses not to be known by that title, I believe as a mark of respect to the late Princess Diana.

Yes, I realise that. But Princes William (who is also heir to the throne) and Harry chose to be styled to put themselves on a more equal footing with their wives. Charles has not.

Technically, Princess Diana should have been styled Princess Charles or Diana, Princess of Wales (as she’s now referred to). But by public acclamation she was Princess Diana – and still is, to many of us.

I increasingly find all this malarkey about titles absurd.

William isn’t the heir yet, and technically he’s William of Wales, and she is Princess William of Wales, I think. Meghan is Princess Henry of Wales. And I think Camilla, Princess of Wales just wouldn’t be an acceptable title to those who think Diana was perfect. (Just because she was pretty. Mutter, mutter!)

Janet, before Stephen interposes and vetoes further discussion, I think you are missing the point that it is Camilla, not Charles, who has opted for this status quo. Had she not done so, they would have been known as the Prince and Princess of Wales. There is no inequality on the part of Charles in that.

Sorry, I’m quite certain that Prince William does not have any such title as William of Wales. The Prince of Wales is not an hereditary title. It is conferred individually by the Monarch conventionally to the Monarch’s eldest son.

Prince William’s correct title is ‘Prince William, Duke of Cambridge’. In the fullness of time he might become Prince of Wales after his father becomes King, and confers it on him.

But I fear we are straying from the real subject – and confusing facts and personal preferences!

Quite true. 😁.

I googled it! 😀.

Good post Stephen. Thank you.

That was a bit naughty of me, but I thought it would get discussion going, and it did!

More seriously, what people are really looking for is authenticity. That’s why programmes like The Repair Shop, Our Yorkshire Farm, and Yorkshire Vet are so popular – they show us people who are genuine, who care, and are helping others without making a big fuss about it. The Church is at its best when it does the same, not when it launches big projects or does lots of shiny PR.

Incidentally, Diana was loved not just because she was beautiful – Princess Michael of Kent was beautiful, too. Diana was loved because she was warm and spontaneous, cutting through a lot of the decorum and formality of the Royal Family. And because time and again she reached out to those on the margins, often visiting hospitals secretly but making gestures like publicly holding the hand of an AIDS patient, or walking through a minefield on camera, when it would do most good. That’s why people forgave her for being so flawed and vulnerable. Harry is loved for the same reason.

The Church could learn a lesson from all this. I think the archbishops, at least, are learning it. But there’s a big problem with the Church’s civil service.

Yes, but Janet, my husband knows someone who is married to a man who was taken off mine clearance to stage that landmine demonstration. And she was sleeping around, hence the persistent stories about Harry’s parentage. I feel for their unhappiness, really I do, and The Crown is a real problem because people can’t tell it from reality. Everyone has feet of clay, and that includes clergy. And we all need to be grown up enough to acknowledge it. And to be honest with each other.

The landmine publicity did a lot to increase public and financial support for landmine charities and clearance.

As for ‘sleeping around’, I think it was a few serial affairs rather than general promiscuity. And she can hardly be blamed for that, seeing as her husband was unfaithful.

In any case, neither of those undermines my point that she was popular and loved despite her obvious flaws, because she had warmth and had time for those on the fringes that no one else in the Establishment was interested in.

And yet this poll, for example, tells a different story, of a major softening of support for the monarchy, especially amongst the young: https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/tnt8vkmjp1/YouGov%20-%20Future%20of%20Royal%20Family%20Results.pdf.

I am rather indifferent about whether or not we continue to have a monarch: we have had a ‘crowned republic’ for at least a century; would it make much difference if we had a substantive republic? Monarchy or republic, the sharp elbows of the affluent will continue to shove those less fortunate into the darkness.

It seems likely that the demographic profile of those who support a tiny coterie of hyper-privileged people living in palaces are not unlike those who are prepared to trust in the bona fides of the clergy. However, it seems likely that the attenuation of support for throne and altar is all of a piece with a decline in respect for institutions in general: in a strongly individualistic culture where we are all ‘consumers’, respect for any form of ‘direction’ will be conditional and vulnerable to sudden shifts in opinion. What goes for prelates and princes also goes for teachers, doctors, the police, lawyers, civil servants, etc., albeit that ‘subaltern’ elements in certain professions will be favoured (such as nurses or the ‘other ranks’ in the armed forces). For example, we have seen public esteem for ‘experts’ during the course of the virus be put on a rollercoaster: in March the experts had been restored to the thrones they occupied before Thatcher (and certainly before Brexit and the GFC); by the middle of the year they had been dethroned, and their current status is uncertain.

However, Stephen is right about the clergy: one people who argue that they are subject to a superior code are found wanting, there is often little way back. The fate of the RCC in Ireland and elsewhere is instructive in this regard, although in Ireland many people were looking for an excuse to slough off the dead hand of the Church by the 1990s, since society had become ‘marketised’ by dint of its growing prosperity. The Church of England has, until recently, congratulated itself – hubristically – on not being like the RCC, and is now suffering the same loss of esteem. This, too, is too often an excuse for many people who want to cast off the vestiges of Christianity: if the outward manifestations of the faith have lost market value then presumably the faith itself can be dispensed with, and without any corresponding loss of social prestige.

Shall we draw a halt to the discussion about titles of the Royal Family? The point of mentioning them was to indicate that sometimes people can regain esteem even when misconduct is admitted. I am completely neutral over the RF but I am deeply concerned were people to start shouting at the clergy in the street, as seems to have happened in Ireland! As I said, it is not only the misconduct that is important in a scandal, it is what people do with it afterwards. Cover-up and reputation management tricks are not the way forward. Let us hope that Mark Arena the new (Australian) director of Comms for the C of E can make a difference.

If I were a hard working clergy person or retiree after a long life of service, I’d be feeling pretty angry right now. The loss of reputation caused by a few is probably irreversible.

Whilst the royal family is relatively circumscribed, and its linen frequently washed in public, the clergy world is not. Hardly a day goes by without some news release about a clergy malfeasance. There is an almost unlimited supply of vicars and pastors and you’d expect a percentage failure if they are human. But because the news appetite is rightly sensitised to hypocrisy, we can’t expect the procession of publicised failures to slow any time soon.

On a societal level we at one time held clergy in high esteem, an overestimation of their purity for example, an idealisation. Actually the pressures on clergy are greater than joe public in the main. The effect on clergy marriages is well documented.

Other professions also have societal idealisation, for example the medical profession. Despite the monitoring by its General Medical Council, I wouldn’t be surprised if the esteem in which doctors are held deteriorates in years to come. When I left, many years ago now, the onset of litigation was just beginning to gather momentum.

I do agree it’s right to “clean house”. The clergy would be well advised to be transparent and completely on top of these matters. It will take courage to continue wearing the collar in public.

“On a societal level we at one time held clergy in high esteem…”

Up to a point. The clergy became increasingly unpopular in the later middle ages, and the Hunne and Standish affairs of 1512-15 lit the anti-clerical torchpaper. Many clergy were similarly reviled in the 1640s: think of the fate of John Lowes of Brandeston (Suffolk). Think also of the high feelings prior to the passage of the Great Reform Act and in the wake of the Jocelyn scandal: Howley was pelted with dead cats, whilst Robert Gray of Bristol had his palace torched by the mob. The bishops could scarcely show their faces. Of course, English anti-clericalism was relatively mild: read Jack McManners’ melancholy tale of Angers during the Terror, when the corpses of so many clergy floated down the Loire, or of the Tragic Week of 1909 and the Spanish civil war, when churches were burnt and clergy hanged, or of Mexico during the Cristero rebellion, or Portgual following the revolution of 1910.

There has long been a dynamic tension between the high ideals vested in the office and the human frailty of the office-holder; ideal and reality and not as often conjoined as we might hope. The difference now is that the prestige of the clergy is arguably bound more closely with the residual prestige of the faith than before. During many past waves of anti-clericalism, the clergy were ridiculed and despised, but the faith endured, not least because the impulse was to cleanse the faith of the corruption associated with the clergy (and especially the higher clergy). Now the faith is so weak that if the clergy fall, the faith risks sinking with them.

Actually, I think that the Church is irreparably tarnished already. Public expectations are now set, and every new scandal simply confirms existing biases. Many Anglican commentators believe things can be turned around if only the Church is ‘reformed’. Well, it seems that a lot of the Church doesn’t want to be reformed, and many think things can be brazened out. As I see it, both the advocates and enemies of reform suffer from the same delusions: they think that the Church can be rehabilitated. Perhaps, but to me it seems far too late.

However, as I have mentioned before, the Church is not the only institution infected with this malaise. Consider the fate of the BBC, for example. It is only a few years ago when it was on the pedestal with the NHS; in 2014, and in the wake of the Savile scandal and other revelations of abuse, the SNP was arguing for its retention in an independent Scotland. Would the SNP be trumpeting the benefits of the BBC today? I’m not convinced it would. Modern Britain echoes to the sound of falling idols. However, there is a risk that endemic cynicism and disenchantment becomes self-fulfilling and society ends up dissolving in its own bile and acid.

I am just grateful for Stephen’s point about admitting misconduct. 14 months in I am further away from that than when I started. Now advisers are suggesting I consider insurance claims,, litigation, going public to the press. Yet all I ever wanted is an admission. So simple. Why so hard?

Hello Jane. My experience is similar—all I ever wanted was for my diocese to help mediate a dispute with my rector. Now, five years later, we’re in litigation in three different states, while my former parish is shedding members (as they say here in the US), like a dog with fleas.

Meanwhile, one sympathetic church official has noted that the harder I push, the more fiercely the church resists. That’s okay, because the church has had numerous chances to do the right thing. Instead, it’s been duplicitous, stupid and ugly at every turn, even going so far as to say in writing that it will only get involved in illegal clergy conduct if criminal charges are brought.

So there it is.

I am going to continue to stick up for myself, and I hope you do the same for yourself.

Love and blessings.

Eric, I am so sorry you have met such resistance and had such a rubbish response.

Five years – you are very resilient! I am glad you continue to stick up for yourself.

Not sure I could manage 5 years, but while I am stepping back from my own case just right now, I don’t intend to give up yet.

Seasons greeting to you and I hope that you, truth and justice win.