One of the important tasks for a parish priest, or anyone involved in Christian instruction, is to help a learning group, like a confirmation class, to deal with symbolic language. Leaving symbolic language to interpret itself without any explanation is a recipe for confusion in a young mind. We have recently been celebrating the feast of the Ascension. This event, told in profoundly symbolic language, cries out for interpretation so that we can make some sense of the text and what it is trying to tell us. We also need to explore the heavily symbolic language of other parts of the Bible, including the Book of Revelation. Young minds can, I believe, cope with the insight that says that symbolic language is a distinct way of communicating truth. In using it we are not committing ourselves to a belief that heaven is somewhere above the clouds. Some conservative teaching about the Bible seems to force the young person to believe that there is no other of dealing with symbolic language. It has to be either literally true or false. I have not come across any conservative teaching which explores a more nuanced way of approaching the issue of symbols in Scripture. Binary ways of thinking seem to be built into the conservative approaches to the Bible. Such dogmatic assumptions and beliefs by a whole swathe of conservative Christians will lead to an insistence that the story of Jesus ascending into the sky (like Elijah before him) has to be believed as a physical event in front of eyewitnesses. Liberal Christians want to affirm that the language about God and his self-revelation is not always told in the language of historical fact. Quite often, the language of symbols is used to evoke truth and divine reality which defy the use of words. Factual statements we call scientific represent a genre of discourse which only works in certain settings. The important issue for us now is to help our fellow Christians to know that there are alternative understandings to the notion of Jesus literally ascending into a cloud. We are not required to follow the ancient writers in their ideas about the nature of the universe and the precise physical location of the Risen /Ascended Christ.

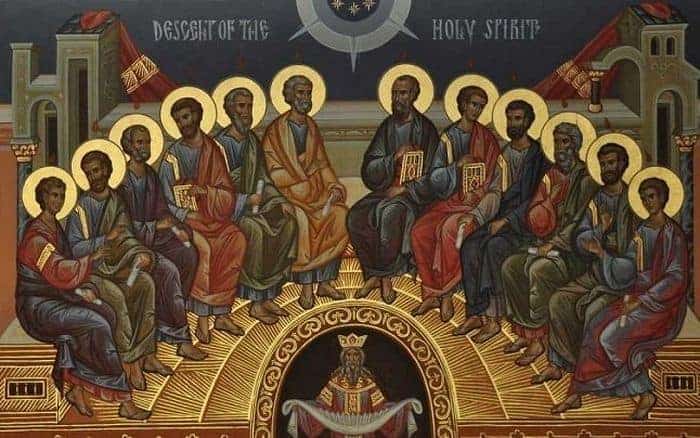

Teaching about symbols and the way that they can communicate truth to us in the Bible and elsewhere, is, I believe, a vital part of Christian formation. One of the privileges of my own theological formation was to spend 10 months among the Orthodox in Greece and elsewhere. I learnt many things through this exposure to a different cultural form of Christianity. Perhaps the most important thing that I learned was the ability to approach truth without depending on the analytic tools of the 18th century Enlightenment. An Orthodox worshipper does not come to church to listen to intellectual sermons. He/she comes to see. Church is a place for religious contemplation through the use of the eyes. Truth is represented largely through visual symbols. Venerating an icon and watching the highly visual drama of the Liturgy are the core means of accessing spiritual reality and the Divine mystery. Such a way of experiencing the Divine is not somehow superior to our cultural heritage. It is simply different. The traditions of the Enlightenment of course have penetrated much of modern secular Greek thought but the value of symbols as a way to encounter deeper reality remains intact within the theological traditions of Orthodoxy. Many in the West are drawn to this contemplative style of approaching truth. It is a way that bypasses the dry logical methods of Western rationalism. There are other areas of knowledge where these Western methods of knowing seem to fall short. We know from ordinary human experience that certain important human realities cannot be embraced by the language of logic or proof. Merely to observe a mother and child interacting on a park bench, is to grasp a reality that cannot be fully contained in the language of a precise verbal formulae. Love, a word which embraces human relationships as well as a fundamental attitude to the world, clearly defies definition.

It is my belief that the task of teaching all Christians, young and old, how to relate better to the rich symbolic language of hymns and scripture readings is a vital task. Trying to fit every visual, symbolic description into the straightjacket of scientific categories is clearly impossible and unhelpful. Every mature Christian should have grown out of the need to hold on to the idea that every statement is some kind of literal description of reality. We should be proud of the fact that the Christian faith and scriptures provide us with a portal into a world of profound truth. We describe this reality as transcendent and it is certainly beyond our ability to measure or control it. To tell a young teenage candidate that the word symbol is an entrance into a deeper richer world is to help them. If he/she is ever left with the idea that statements in Scripture are either literally true or false, that is immensely impoverishing. The word symbol means, literally, something which has been thrown together or connected with another reality. The word suggests absence and presence at the same time. We could, in many cases, make a translation of the word by calling it a door. The Ascension season hymns on Sunday morning were especially full symbolic language. Jesus is the one who ascends to be with his Father in a place of light and glory. How we deal with this language is enormously important. We need this language of Ascension, but we do not solve the problem of what it means by insisting that we take it literally.

The week we are in, is now building up to the feast of Pentecost. While I was reflecting during the Sunday morning’s service, I found myself making a contrast between the symbolic language of Ascension and the relatively concrete description of the coming of the Holy Spirit. Of course, we find symbolic expressions in the Acts account of the coming of the Spirit. We have the clearly symbolic language of tongues of flame. But this choice of words communicates physical realities, energy, power and heat. These words also communicate the concrete ideas of inspiration and insight. Explaining the importance of the Pentecost feast to our imaginary confirmation candidate, we might want to emphasise two key, but not necessarily religious, ideas of power and inspiration. Both these words have a currency in everyday experience as well in our moments of religious insight.

If I were having to teach about the feast of Pentecost to a congregation, I would attempt to tap into the everyday experiences of each of those listening. I would ask about their experience when they are consciously looking for guidance to do the right thing in a difficult situation. Putting aside the language of flames, wind and excitement, I would ask them to relate to the other more mundane ideas that maybe are evoked in them by the symbolic descriptions of the Holy Spirit. Most people can describe what inspiration means to them at a personal level. It has to do with the unexpected surge of energy and insight comes to us when we are open to receive it. Obviously, the word will have a variety of meanings, only some of which will be spiritual. But I suspect that when people do grapple with the word, they will find themselves not far from what Christians are talking about when they refer to the one who is the Lord, the Giver of Life. It is certainly important to link the human experience of inspiration with the whole encounter we associate with prayer and the search for spiritual guidance.

The teaching about the Spirit also brings us once more to consider the word power in a human context. We talk about power a great deal on this blog but often in its negative manifestations. But, of course, there are positive forms of human power. It is because of this power from the ‘Giver of Life’ that we understand ourselves to be both human and. at the same time, spiritual creatures. When I reflect on my own spiritual experience of power, it will link into the extraordinary way that that I have sometimes found the resources to do a particular work or overcome a particular problem which seemed at first impossible. Coming through difficult experiences and finding that I had said words which I did not know I possessed, has made me realise that the power, the energy and inspiration of the Holy Spirit is quite often around us and in us. Of course, Pentecost is a festival mainly for the whole Church. But it is also a festival for each individual Christian as he/she struggles to move forward along the Christian path. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of life, can be interpreted to say that we believe God is acting through his Spirit in us when we open ourselves to him. The language of Pentecost according to Scripture is close to the language of twenty first century experience. It is the language of power and inspiration, guiding us and leading us through life.

My insight last Sunday morning was see that this season of Ascension-tide begins with the most densely symbolic part of Scripture and ends with the practical language of inspiration and power at Pentecost. Christians are the heirs to both forms of teaching, the symbolic language and the more grounded and practical. The symbols of Ascension appeal to our imagination and our capacity to see God through the medium of highly visual language. The more concrete account of the day of Pentecost brings us back to the way that some ordinary human experience intersects with the divine. Pentecost may indeed be the feast of the birth of the Church, but it is also the feast of individual divine inspiration and power. It takes areas of our human experience and gives to them some access to an encounter with the divine. Through the Holy Spirit we are allowed to experience the highest expression of power, as our life is linked to the vitality and Spirit of God himself.

A long and thoughtful piece Stephen, thanks. The complexities of what was about to happen with in presence of Christ no longer going to be available to his disciples in a physical way but without Him ‘leaving them as orphans’ would stretch the imagination and intellect of us all. How could we teach those 1st Century simple fishermen? How could we convey something of the mystery of God in Christ but coming in Man? This was what faced Jesus. His answer was to rise from the Earth into the clouds in an acted-out demonstration that would begin the process of illumination in them …. and in us.

I agree that understanding symbolism is of vital importance for Christian growth. In fact, it was learning about symbolism and imagery while reading English at university that set me on the path which led to my becoming an Anglican and, gradually, to understanding much of the Scriptures in a less literal way.

However, I don’t agree that the Ascension should be understood as a purely symbolic account rather than a physical event with eyewitnesses. It is recounted in Mark, in Luke, and again (with more detail) in Acts. Luke in particular was careful to produce a reliable account of events which had witnesses and could be checked. It would have undermined the credibility of his other narratives in Luke and Acts if his account of Jesus’ departure from earth could have been shown to be fanciful.

What I do think is that, although the Ascension happened as Luke relates it, it was done that way so that the disciples understood that they couldn’t expect to see Jesus in the flesh again. From now on they must expect to meet him in other ways, in their experience of the Holy Spirit, and in each other. In that sense it was symbolic, because the physical symbolism was necessary for their understanding. We are not to understand by it that Jesus literally went straight up from Israel and kept going until he reached the stars; or that when we die we will eventually find ourselves in the troposphere.

‘The kingdom of heaven is within you.’

The Ascension is certainly mentioned or presupposed by lots of early writers (Rom-Heb-Eph-Col on the heavenly session and Christ’s current presence in heaven); John 3, 20; Luke-Acts-1Tim (‘taken up’ – echoing the Elijah narrative, as so much of Luke-Acts does). This shows that the question of where is Jesus now had arisen, and was consistently answered by his being in heaven at the right hand of God, as Ps 110 could tell one.

If there is a trajectory here it is from Christ’s heavenly presence towards a greater emphasis on how he might have got there.

The ‘Mark’ reference is not Mark but a later addition, perhaps somewhat Lukan and seeming to postdate and reflect Luke’s narrative which is c95.

This sort of trajectory would chime with those who would want to question why so momentous an event failed to be mentioned earlier than 95AD.

Where do you get the 95 AD date for Luke and Acts?

Dates (some of them tentative, some more assured) are obtained by reviewing the combination of all relevant factors. In this case, that is a large number of factors. By far the main thing in dating is the network of literary interrelationships between different writings, together with the final historical references within those writings. In researching my paper for Tyndale NT Conference 2019 I was struck by the way that the parallels between Luke and 1 Clement indicated Luke’s priority (the level of analysis here is quite micro, but based on fairly firm principles which I enunciated) whereas those between 1 Clement and Acts indicated 1 Clement’s priority, a consideration that anchors Luke-Acts’s dating as Acts is unlikely to postdate Luke by much; also Adversus Apionem postdates Josephus’s Jewish War of 93AD (with Josephus’s Vita in between) and yet seems to prefigure Luke’s prefaces. But 1 Clement is generally put in 95-6 because of a large combination of factors – none of which is conclusive, but all of which taken together make it hard to date it later (or much earlier) – as indeed it would be difficult to date Acts much later considering it was written by a companion of Paul. Luke-Acts has to postdate Matthew and both have to postdate John. All scholars try to take into account all relevant factors, and 95 would be within the range of typical dates assigned.

Thanks, that’s interesting. I have to say I’ve never been interested in he dates and sources stuff, with the result that I’ve never really looked into it.

When I was at theological college the source analysis we were being taught had been discredited long before in non-biblical literary criticism, which resulted in my being sceptical of the whole field. But perhaps I ought to take dating analysis a little more seriously.

Have you read The Jesus Papyrus by Carsten Peter Thiede and Matthew D’Ancona, Janet? A stunning read. So interesting and intriguing.

Dating is tricky. During lunch in the echoing dining hall at Trinity College Bristol in the 1980s, I was seated opposite a girl and we were talking about our favourite foods. She happened to say passionately, “I love dates” just as the room fell unaccountably silent. The words rang out loudly, to her total confusion.

A gospel of uncertainty is a difficult “sell”.

Many churches meet in schools or cinemas or other perhaps neutral, maybe bland places with little imagery available. Sometimes deliberately so.

It takes some maturity of character to live with doubt, to carry on despite not knowing what exactly is going to happen to us, and being ok with this. You only have to hear responses to the latest iteration of Covid-19 travel advice. There is some frustration, some outrage even at having to take a risk without someone to blame, or take responsibility for what we may want to do or go.

Into this brief glimpse of humanity, the churches have cast their net to catch souls for The Risen Christ. Some have set out with a definitive set of answers, and some have not.

Whilst prescriptive messaging has a distinct advantage, at least initially, a lifetime of lived experience and empirical uncertainty eventually seems to lead us into a more understanding and less judgmental direction.

In the end we may no longer need to know exactly how Christ wasn’t physically there any more. Suffice to know He still retains His presence among us. Moreover it’s reassuring to know we have no control whatsoever over It. Or Him. What kind of God would He be if we could?

Thanks Stephen. I am not sure about teaching young people in the way you suggest. Personally, I like the way the Bible is not always clear as to whether a passage should be taken literally or figuratively. I saw a video about the Mark of the Beast recently in which the speaker said that when reading Revelation, his mind was continually flipping between taking things literally and taking them figuratively, and it is often unclear which is which. His take on the mark, for example, was that this is not a physical mark, but like the statements in Deuteronomy (“Wear them on your forehead and pout them on your doorpost”) it is a powerful mental image. Personally, I take the mark of the beast literally. Who knows which is right? I don’t myself want anyone trying to persuade me one way or the other.

Good fun.

Those are good examples, David. Observant Jews did, and still do, literally wear the Commandments and put them in a little box on the doorpost (called a mezuzah, though I may have spelled that wrong). Whereas Revelation is a kind of literature called Apocalyptic, and was always intended and understand as symbolic. The meaning is hidden. It was a useful device when writing to people living under enemy oppression – it couldn’t be recognised as subversive because the meaning wasn’t understood.

The generations of (mostly American) preachers and writers who have speculated on the nature of the mark of the beast haven’t understood this. The first task when reading any Bible passage is to understand what kind of literature it is – that’s why it’s important that Luke carefully researched and intended his gospel and Acts to be accurate records. John wrote with a different intention.

The priority of genre in interpretation: exactly.

Revelation would not be much *use* to anybody if its meaning were hidden to *everybody*. Nor would a symbolism that hid *everything* be of high spiritual value, nor worthy of our praise, because the edification would be zero. That is why the book calls for wisdom in ch13, meaning that with a little effort that which is communicated in a covert manner regarding contemporary events can be uncovered. It is quite correct to say that contemporary events are alluded to in a covert manner in Rev., unsurprisingly when emperors are involved. The high proportion of the book that does not allude to contemporary events is a narrative which is not symbolic of anything else.

Maybe Revelation shouldn’t be there! A number of scholars think so.

Splendid Janet. Thanks. I love all this kind of thing!

PS Genesis one was never intended to be a scientific paper…

Indeed. I tend to see it as a statement of faith. Even a hymn, it’s in strophes.