The forthcoming Jubilee has allowed the older ones among us to dredge our memories to recall where we were when the news of the death of King George was announced to the nation. I was in my two-form rural primary school in Kent. One of the children from the class above came into our form room to announce the news. The broadcast of Music with Movement for schools had been interrupted to share the news with the public. I do not remember any strong signs of emotion being displayed. More shocking was the announcement of the assassination of President Kennedy eleven years later. The violent death of prominent people was not something that we were used to at the time or expected.

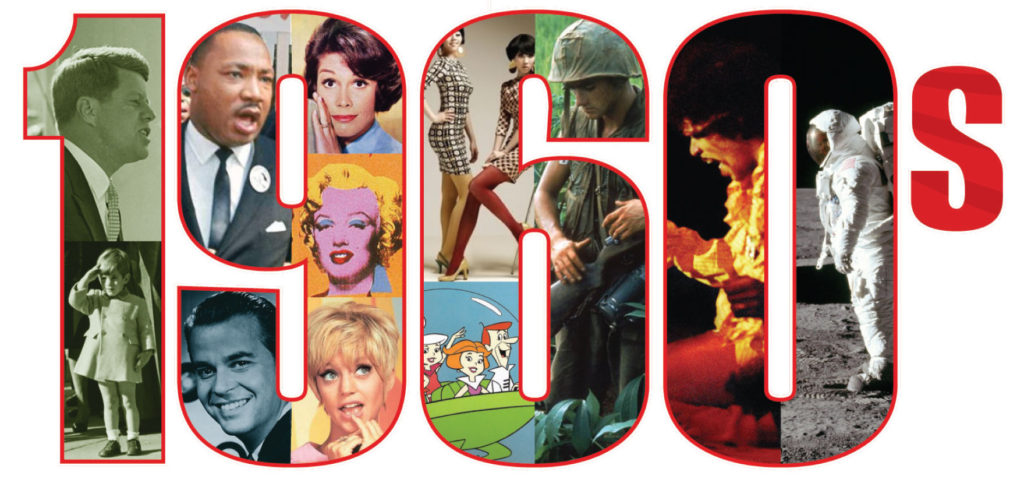

Reading accounts of past events that we were part of, in some sense, is a fascinating exercise. One thing that is of interest to me is to reflect and discover how long it took for any sense of party politics to enter my thinking and my imagination. As a student in the mid-60s there was a great deal of political activity going on around me, but I did little to get involved. Everything seemed to be pointing the way to a political revolution that many believed to be imminent. The Vietnam war was polarising the young people of my age in the States. The short but bloody 1968 confrontation between the Russian tanks and the crowds of Prague was heroic, inspiring and tragic all at the same time. The student uprising of the same year in Paris galvanised many young people into political awareness and activism. I was one of those who, until the end of my time as an undergraduate, was a complete political innocent. It took a prolonged stay in Greece under the Colonels to awaken any political fire inside me. My exposure there to a cruel fascism introduced me to the emotion of political passion. For the first time I began to be able to imagine something of the zealotry of young people around the world, who at that time were prepared to risk their lives to change a political system.

Politics is not only about a dominant group which makes the rules that govern a country. Alongside the ideology of a ruling party in government we have other levels of political activity, as, for example, the belief systems of institutions. In the late sixties, speaking in a very generalised way, it could be said that the universities and churches were predominately in a left-wing mode. For me, a participation in this ideological social movement was experienced by my attendance at a huge student conference in Manchester in 1969. This conference was entitled Third World First. The very definite left-wing bias of some of the speakers was apparent in their use of incomprehensible Marxist jargon. These were hard to listen to or understand. There was enough, however, to latch on to elsewhere to make it worthwhile. We had the inspiring words of Archbishop Helder Camara of Recife in Brazil. He helped to convince his audience that the future that beckoned us had a distinctively socialist feel.

Beyond the world of politics and universities there was yet another ‘lefty’ revolution going on, this time in the theology of the churches. In a revealing chapter in her recent book with Nicholas Peter Harvey, Unknowing God, Linda Woodhead speaks of the communitarian strand of modern philosophy and theology. This was flourishing in the sixties and, according to Woodhead, was typically expounded by the influential philosopher John MacMurray. This writer had a great influence on my own thinking from the time I read one of his books in 1964. The theme of much of MacMurray’s writing is a simple one. He articulates the idea that each of us only finds ourselves in our relationships with other people. In other words, community is the primary reality, and it takes precedence over our individuality. In this mode of thinking we find several other theologies which emphasise the communal and which were very popular and influential in this period. Among them we have feminist theology and liberation theology. Both are examples of Christians attempting to explore theology as it touches groups. At the time, like many others, I found such ideas enormously attractive. They also fitted with another strand of theology which I was learning from my study of Orthodoxy. The theme that I was noting is summed up in the word Sobornost. This is one of those words that is best not translated. It is a Russian word which is itself a translation of the Greek word koinonia. That word has the idea of human community and participation in the divine. At theological college I was attracted to the ideas of John Zizoulas who wrote a work on the eucharist. He claimed that the church finds its true identity as it gathers to celebrate this rite of communion with God which also binds together its members.

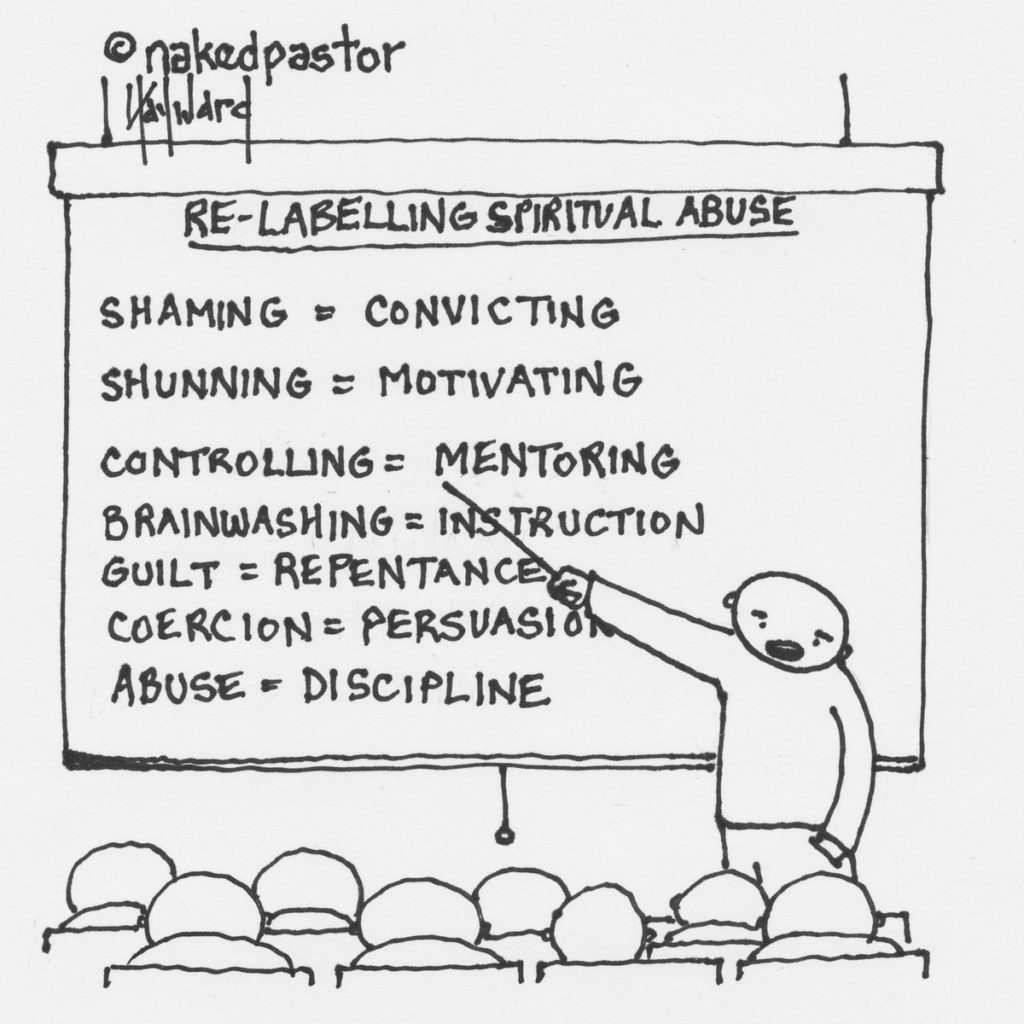

Looking back, I can see how thoroughly immersed I was in the communitarian ideas that were current in the sixties. Woodhead’s short essay has allowed me to recognise how much I was feeding on the prevailing fashions of the time. There is nothing shameful about this attraction, but the dangers of going too far down this path can be faced afresh as we look back. Woodhead’s writing is able to point out, from a contemporary perspective, the drawbacks of taking on too much of this mode of thought. One of the interesting expressions of this thinking was the wide embrace across the Western world of a belief in communes. Many, if not most of these experiments, ended in tears as the idealism which started them could not overcome the many practical issues that this kind of community living involves. I have also listened to endless accounts of the ‘cults’ where idealism was betrayed so that a community became a focus of pure exploitative power. One student at my theological college went off to live in a commune immediately after ordination. This was supposed to be a great new idea in politics and in the church. Too much idealism does not solve problems like responsibility for cleaning and washing up. The Christian commune at Blackheath survived only a couple of years.

Woodhead’s article is of great value as it sets out the danger of a church life and a theology that draws deeply from this communal vision. She also recognises that the opposite to it, what she calls atomised existence, is conducive to loneliness and isolation. Any excess of community is often going to be claustrophobic and dangerous. Community of the wrong kind can involve the loosening of barriers that mark out where we end and another begins. This can be exhilarating but we all need appropriate boundaries to defend and protect us from exploitation, bullying and abuse of various kinds. Finding the right balance between atomised existence and an over-intimate association with others is difficult. The article dramatically points to the way that sexual abuse is a forcible wrecking of the needed boundaries that should exist between us and others. We desperately need them for our psychological and emotional well-being.

We all face the problem of finding out who we truly are. Over the 10 years when I have been involved in cult survivor circles, I have seen how easily people can become sucked into extremes of community living. They give so much of themselves to the cult, its leader and the ideals of the group, that it is extremely hard later to escape and find their true self once more. I wonder sometimes whether church groups understand the dangers of what appear to be cult-like practices in their communities. We recently mentioned the dynamics of the John Smyth ‘cult’. He completely undermined the self-determination and identity of his young victims. For many of them the task of reconstructing the self is still proceeding some 40 years later. Peter Ball did something similar to his victims. It took exceptional courage for survivors in both cases to step forward and make a complaint. Simultaneously we need to remember that not by any stretch of the imagination is everything about religious community bad. The danger here is when such communities allow their members to step over a line into a form of undifferentiated merging with others. We need to spend more time addressing this tension in church life and how we need to preserve a healthy place which balances our need both for community and individuality. The same balance is needed in our political life. Fortunately, we have the resources of Scripture to help us to find who we truly are in Christ. We never need to be enslaved in the ideology and control of another person.

Over my lifetime I have seen in politics and religion the oscillations between promoting strong independent individualism and the insistence on new forms of tight community. On this blog we have noted the tension between placing ourselves under a strong charismatic leader or seeking to go it alone. It is indeed hard to find exactly the right place to be along this spectrum. The place of true balance in our religious and our political life is, nevertheless, worth searching for. The two extremes of total independence and a merged personality have to be wrong, both from the theological and the psychological perspective. The important thing for a Christian is to understand the seductive nature of both these positions so that they can avoid embracing either of them. We are not meant either to be a strong superman/woman, owing nothing to anyone or, on the other hand, a porous personality able to be swayed and manipulated by everyone in sight. I believe that the resources of Scripture combined with an intelligent reading of the psychological literature can help us to know what is, for each of us, healthy territory to occupy. My short reflection here on this post has perhaps made us aware of a map that needs to be drawn by each of us. That map may help us to live in the right place, a place that is simultaneously open to God, to other people and to our true selves.