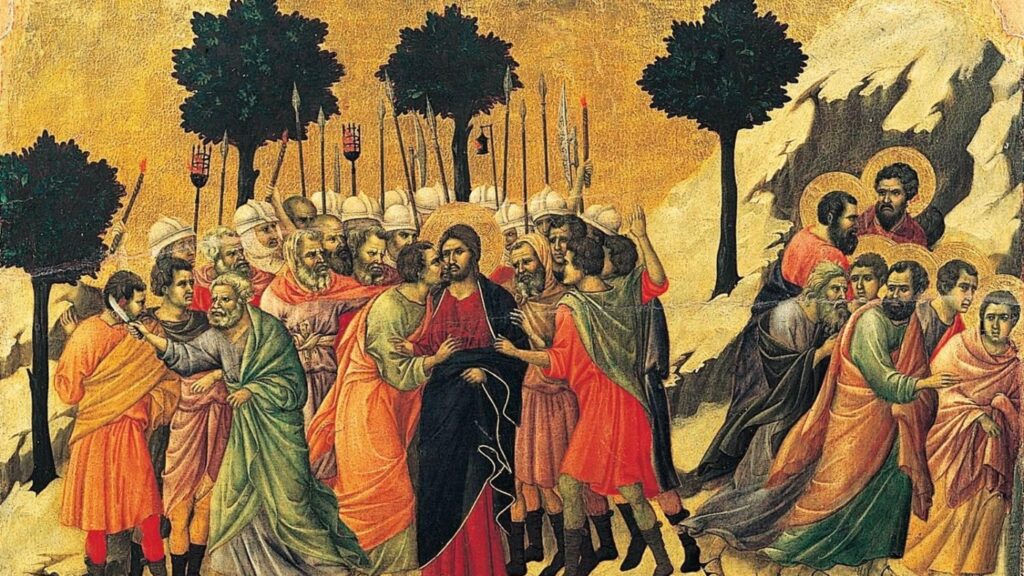

There is one word which opens up for us some important aspects of the Holy Week drama. The word is betrayal. In our liturgical commemoration of the Passion drama, we are, early on, witnesses of the betrayal by Judas. Then there is the somewhat different manifestation of betrayal by Peter during the trial of Jesus. In reminding my readers of these particular moments of betrayal in the Passion narrative, I am not intending to launch into a full Holy Week meditation. Rather I want us to reflect on the meaning of the word betrayal and the way that it touches us in our personal and social lives.

In considering these two betrayals mentioned in the Holy Week narrative, we can see that there is more than one way of approaching the word. First there is betrayal as an objective fact. Jesus is delivered into the hands of the authorities by the actions of Judas, a member of his group and then later disowned by another disciple, Peter. Then there is the subjective side to this act of betrayal. We have to imagine all the feelings that would have been aroused in Jesus because of the actions of both Peter and Judas. The objective betrayals were accompanied by the shattering awareness for Jesus that profound prior relationships were being attacked and, in one case, destroyed. Further emotions are recorded in the account of Peter’s betrayal. There was, for Peter, the emotion of anger in the denials. Later there were profound tears of contrition and regret. Before we leave the words recorded in Scripture about betrayal, I want to remind my reader of the psalmist (Psalm 55) who also experienced the deep pain of betrayal by a close friend. He expresses the thought that if it had been an open enemy who had betrayed him, ‘then I could have borne it’. The fact that it was a friend made the betrayal doubly painful and unbearable. Most of us can probably remember occasions where similar things have happened to us. I can remember an incident from the time I first went to public school at the age of 14. It was quite a culture shock to go from a school with 60 boys to one with 350. On the very first day I struck up a friendship with a boy from another house who sat immediately behind me in the class I was in. It was a relief to know that there was a potential ally literally watching my back, and this helped me to cope with the sheer strangeness of everything around me. Imagine my shock and disappointment when the same boy, for reasons that remain obscure to me, shortly afterwards decided to stick a pin through the canvas webbing of the chair I was sitting on. It was not the pain that I felt most of all. It was a sense of betrayal that a potential friendship had been so suddenly destroyed. All of us have probably known this experience of trusting an individual, only to have our trust in that person wiped out by some act of betrayal. All of us want to believe that those close to us are incapable of such acts. Most of the time, thankfully, we are right. Then, once in a while we are completely dumbfounded by an action taken against us by someone we thought we knew well. This revealed a hidden malevolence which we did not understand and probably had never seen before

My involvement in listening to stories of abusive behaviour in church contexts has made me aware of the way that otherwise loving people even in churches can turn out to have a dark side. In the one place where we believe sound caring relationships are promoted and valued, it is shocking to discover acts of betrayal which merit the description of abusive or exploitative. As we are never tired of saying in this blog, acts of betrayal are not just found in the original abusive episode; they are also frequently in the way the survivor, seeking help, is treated by church people in authority. Betrayal is thus experienced by the abused person in a double act of violence. Through abuse, a youth leader might destroy our sense of safety and well-being in a church, but then the same thing happens when we, the abused, reach out for help from another respected leader. Even if these leaders are held up by others as totally trustworthy with high reputations, the experience in fact we have gained is one of double betrayal.

One of the issues that the 31:8 review about Emmanuel church Wimbledon struggled with was trying to make sense of the two sides of the Vicar, Jonathan Fletcher (JF). He was the possessor of ‘positive characteristics and (was) highly regarded’. At the same time he ‘could nonetheless display entirely inappropriate, abusive and harmful behaviour which render (him) unfit for office.’ It is clear from the review that JF was found to be charismatic, charming and an inspiring teacher of Scripture. He presented to many grateful acolytes, both this charm and his apparent deep pastoral concern for them. At the same time there was a darker, exploitative and sinister side to his personality. Some experienced bullying and others were victims of entirely inappropriate behaviour, both sexual and psychological. The review tries to grapple with this double-sided reality. One heading in the review articulates the paradox with the words ‘the myth of homogeneity. I had to pause to work out what the review author meant by these words. He/she was pointing to the phenomenon that individuals, particularly Christians, have a tendency to lump individuals into an ‘all-good’ or ‘all-bad’ category. Such lazy thinking does not allow for the possibility that any individual may combine good and bad in the same personality. The 31:8 review is challenging us, in using this expression the myth of homogeneity, to see that theories of all-goodness or all badness in an individual are unsafe, even dangerous, notions to entertain. The charm of the charismatic figure must never allow us to leave anyone with a free pass to be unsupervised and unchallenged for the way they interact with others. Everyone is potentially capable of exploitative evil. To put it another way, everyone is capable of betraying their good persona and surrendering to a dark, even evil, expression of themselves. There must always be structures in place which inhibit and stand against any inappropriate crossing of boundaries. This is where so much abuse and exploitation is to be found. On a positive note, this checking of boundaries in people’s behaviour may have the desired effect of driving away bad behaviour. We need a dominance of goodness and total integrity in an institution to allow people to trust and feel safe again. The opposite sense, fear and constant suspicion, is a high price to pay because some church leaders are too lazy or unwilling to do the necessary work of effective safeguarding for all members of a Church.

The myth of homogeneity is a useful expression to have in our minds as we try to understand why there are currently so many problems in the safeguarding world of the Church of England. Just because someone has passed through various hoops to become a Christian leader and a person commanding trust, it does not mean that they should ever be left unsupervised or beyond challenge in the realm of human relationships and the oversight of justice. A person may reach the status of being a spiritual director of some renown, but a potential for something to go wrong still remains. I am constantly disappointed in the way that I hear of otherwise honourable people in the church behaving, not necessarily abusively, but in ways that are a betrayal of the roles they hold as guardians of justice and integrity in the church. Because Christians talk about holiness, it is often assumed that all members of the Church are incapable of dishonest or dishonourable behaviour. As far as church leaders are concerned, we all too often see protection of the institution being put well above the need for personal integrity. Homogeneity in individuals is indeed a myth. Outward charm is not infrequently combined with self-seeking and actual malfeasance. Eventually some objective scrutiny from outside bodies, even that provided by a secular state, may be needed. It will perhaps be the necessary price we have to pay to get things properly safe and fit for purpose in the task of the Church to protect the vulnerable.

Our theme of betrayal began when we considered particular episodes among the events of Holy Week. From there we moved on to consider our own experience of being let down by others, and, maybe, the times we have been guilty of failing in this way. It may be part of our Holy Week meditation to reflect on the ways that we have been guilty of betrayal whether of Jesus or other people. As we contemplate our own collusion in the guilt of actual betrayal, we are perhaps better able to see that our good intentions can be interlaced with evil and exploitative motivation. Even if evil is not the central reality in the core of our being, we still need to be working all the time at expelling selfishness as much as we can. The first stage of expending evil is to recognise that it exists. Perhaps this Holy Week we can continue the task of greater self-knowledge so that we can individually and corporately become the instruments of God’s active love and goodness in the world.

The other side of the coin of betrayal for victims of abuse is loss of trust.

I was abused by a man I misguidedly trusted. I was betrayed by the Iwerne network, the Christian community I spent all my time with, and then by elders within that network. I disclosed the John Smyth abuse over 11 years ago, and was betrayed by the Diocese of Ely, by Lambeth Palace and Justin Welby ( who will have known the majority of Smyth’s victims in the 1980s). I was betrayed by the response of the National Safeguarding Team and by the slow investigation by the Police. I was betrayed by the delays to setting up the Makin Review, and have been betrayed by its never ending delays. I have been betrayed by a Church that appears incapable of a pastoral response to victims. I have been betrayed by extraordinary breaches of my confidentiality by Isabel Hamley, Chaplain to the Archbishop, by Maggie Atkinson, by three other employees of the Church of England. I have been betrayed by being fobbed off by senior figures. I have been betrayed by the absence of any kind of meaningful Redress. I have been betrayed by the absolute denial of liability by Titus Trust and Scripture Union. I have been betrayed by the appointment of Meg Munn to the Chair of the ISB.

I was betrayed, in 1982, by the belief system, the God, the evangelical construct ( or cult) that I had thrown my everything into.

With each betrayal, I lose Trust. Who can I trust ? And it makes me hyper sensitive to the slightest misstep. Trust is hard won, and so easily lost. It has given me an enormous insecurity and an inability to trust.

Betrayal. Yes, I know about betrayal.

Graham, I am Greek Orthodox and our Easter, (Pascha) was this weekend. I re- read this blog on our Good Friday and read your comment. I have no idea how I missed it the first time as I read the blog some time ago. I most certainly did not miss it on April 14th.

Reading your comment, as I did at such a time of Good Friday, I was profoundly affected by such a story of personal betrayal. There is nothing I can say or do for you and that is the frustration; I cannot help, I am powerless. I am able to pray for you though. I am a great believer in the power of prayer. I can put you in the Hands of God and will do so.

Thank you for this reflection betrayal is an odd feeling to me. As essentially a familial abuse survivor from a very young age I grew up with no one to trust, indeed I had no real concept of what trust was but by the same token no really well defined concept of betrayal.

Perhaps betrayal is more keenly felt when there is also safety in your life so that the contrast is stark. From years of mental health treatment I realise I am amongst many seriously abused familial survivors that struggle to understand betrayal because we were never allowed to understand trust.

Perhaps then being able to feel betrayed also means that you have been able to feel trust.

I can identify with that. I learned to trust only as an adult, slowly and painfully. Still learning, in fact.

Holy Week, and particularly Good Friday, has long been the most meaningful part of the Christian year for me. When I reflect on the ways in which Jesus was betrayed, particularly by the religious authorities for political reasons, I know that he is with me in the times I have been betrayed and understands how I feel. It makes me feel close to him.

He, and we, are betrayed for many reasons – ‘through ignorance, through weakness, through deliberate fault.’ I find it helps to distinguish between those causes of betrayal, though many survivors see all betrayals as deliberate. I can cut some slack to those who have let me down through ignorance, weakness, or what they perceive as a conflict of loyalties. I have not always made the right choices myself, and have let people down. Sometimes I might not be aware that I have done so, because I am still in ignorance.

I find it reassuring that Jesus forgave and restored Peter for betraying him out of cowardice. The gospels don’t tell us, as far as I can recall, that Jesus forgave the chief priest, Pilate, Judas, and others who gave him up to be crucified deliberately, knowing he had done no wrong. Preachers and commentators seem to be strangely silent on that point.

Janet, According to Luke’s gospel (Luke 23 v. 34; NIV) after being nailed to the cross Jesus said: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing,” —though a footnote in the NIV says “Some early manuscripts do not have this sentence” and it is not in any of the other gospel accounts. It is, though, one of the traditional ‘seven last words from the cross’.

If Jesus did say that, it is not clear who the ‘they’ are. Was he referring to all those who had been complicit in his execution, including the chief priests and teachers of the law (Luke 22 v. 66 to 71 and 23 vv. 1,10), Herod ,and Pilate; or was he referring only to the soldiers who carried out the execution and (possibly) the baying crowd who shouted for Barabbas to be released and for Jesus to be crucified—a demand that eventually Pilate gave in to? (The forgiveness of Peter is not explicit, but implicit in his restoration as recorded in John 21 vv 15-17.)

The striking reflection for me this Holy Week is that by former hand surgeon, the Revd Lore Chumbley, ‘Hands that healed sore wounded’, in this week’s Church Times (page 25), concluding “We—that is you and me, all of us—are Christ’s hands, wounded, scarred, but still the precious interface through which God chooses to interact with the world.” I shall be listening to her meditation at 3.00 pm this afternoon on BBC Radio 4.

Hi David. I have long assumed ‘they know not what they do’ to refer to the soldiers who carried out the crucifixion, who were around him when he said it. Jesus didn’t say it when he was before the chief priest, Sanhedrin, Herod, or Pilate, all of whom knew that Jesus had done nothing deserving crucifixion. But I may be interpreting it too narrowly.

Just to add that Revd Lore Chumbley is the much liked priest in charge at Christchurch in Bath – it’s a liberal inclusive church – pretty good on safeguarding and somewhere I finally feel most of the time I can more or less belong …

I am sorry that some feel a deep sense of betrayal, and others have yet to learn to trust, as a result of church leaders. Stephen writes about the need for appropriate structures and the need for total integrity and goodness. Most readers are aware how much the leaders of the Church are falling short. This morning my Rector proclaimed the Gospel, waving the Bible high. He preaching was to contrast lies, deviousness and so on with another proclamation of the Risen Lord. He wore the white robes of purity. However he has ignored five requests from me for being on the prayer list at a time of great family need. We have a youngish member of the immediate family facing terminal illness. A younger one still is facing a serious operation. A younger one still has a disability requiring much time and care from the same family members. And I too have been ill. In such a small family circle the strain is immense. Yet despite asking five times, I hear others prayed for week by week but not us. We are ignored by the Rector. So I have twice complained to the Bishop. I pointed out that he failed to take action previously when my Rector wrote denying me pastoral care and telling me not to ask for it at another time of need. I asked the Bishop to make sure arrangements were made to give me pastoral care. The Bishop has ignored me. Just as he ignored my formal complaint about the Rector. Whatever the current structures, the Bishop permits such misconduct. Goodness and integrity are entirely missing from clergy in my Diocese who act like this against someone who proved the previous incumbent guilty of failing to follow safeguarding guidelines and other offences. Even after the lengthy period of Lent, preparing for the message of Easter, consciences have not been pricked sufficiently to put an end to a wicked campaign against a victim. The Rector did pace up and down and round the Church appearing nervous and nervously making one mistake after another. There can be no peace, either for the abused, abusers, and those who protect them, until clergy take seriously their own proclamation of the good news freely on offer to all. We will all continue to suffer from the inaction of clergy and others who ignore the claims of justice, whilst reading and preaching about them. Sadly I fear trust will not be restored for those already abused. Sadly there are probably new church members who are now being betrayed, and those who no doubt will be betrayed in the future. When will it stop?

Mary, I am so sorry that you are being treated so badly. I should like you to know that I am putting you and your family on my permanent daily prayer list. That will be every day not just sometimes. I shall put you on the church prayer list as well. x

My daily list, too. I have a new baby granddaughter. I would want prayer for her.

Yes indeed EA.

Thank you, that is much appreciated. My treatment has ended now,but everything else remains the same.

People are all mixed up, that’s a fact. So you can be thankful for the good someone does without expecting them to be perfect. If, indeed, they are not just less than perfect, but actually behaving very badly indeed, the good things they have done cannot be used to offset the bad. The very human idea of buying salvation for what we did by building churches and so on, another form of this, is also a myth. At this time of year it must surely be even clearer. Jesus can, and did, buy salvation, we can’t. So in a sense, we can ignore the good things a bad person does. No need to be confused or surprised. I’m afraid their sons are more important.

That’s “sins”!