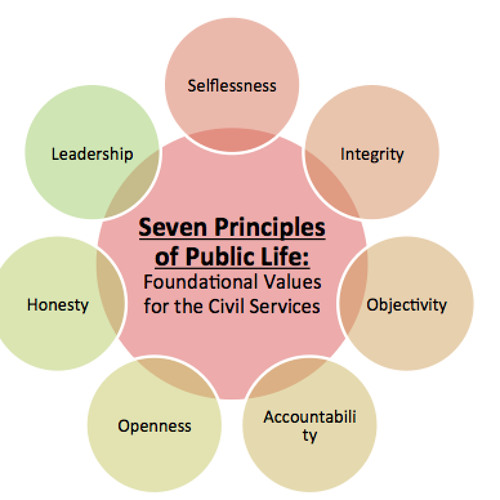

Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty and Leadership.

The list of words above summarise a report published under the chairmanship of Lord Nolan In 1995. This document was a statement of the ethical principles and standards which should undergird the conduct of public life in Britain. The institutions that might adopt these cardinal values include educational establishments, hospitals or departments of government. Another similar statement of governing principles is published by the Charity Commission to state what should guide the conduct of every organisation regarding itself as a charity. At a moment, post-Wilkinson, when the Church of England and its structures are being scrutinised in order to discover whether they follow a set of values that are recognisably ethical, it is helpful to revisit these Nolan principles to see whether the Church reaches or even aspires to the standard of ethics that they express.

Institutions of every kind express the aspirations and aims of the organisation in a so-called mission statement; they set out what they think the organisation is for. They do not routinely give us any insight into the deeper ethical values that are observed (or not) by the respective bodies. A potential conflict between organisational aims and ethical principles is often observable in the world of politics. It is hard not to be cynical about many of the high-sounding statements of politicians when, often, what one discerns at a deeper level is the pursuit of financial gain and political power. Far too often in my lifetime a British government has been forced to give way to the opposition party because the sleaze and dishonesty have become just too obvious for the voters to ignore. It hurts every time a trusted politician is shown to be unable to do what he/she is paid to do – to serve the people of Britain by putting the public interest at the front of their concerns.

What is wrong with many of our public institutions, of which the Church is one? In attempting to respond to a common feeling of malaise around institutions, I am going to risk making a generalisation about human nature. This may seem unfair, but it is rooted in the observations of Lord Acton about power over a century ago. My claim is that most individuals are honest and upright when working and living in small units, like the family or a small business. An inherent honesty practised by the individual is, unfortunately, harder to maintain when the same person comes to work for and place his/her loyalty with a larger group. The focus of loyalty may shift away from the ethics of individuals working in a small unit and change to become a slavish devotion to the large corporate entity they now work for. This ‘worship’ of the large institution, especially coming from the ones who take responsibility for running it, can have a severely detrimental effect on personal integrity and conscience. Powerful leaders of many organisations/corporations rarely seem to come through retaining all the old values of individual integrity. Few people, if any, manage the responsibilities of wielding institutional power without becoming somewhere morally compromised by the process.

Returning to the seven words that summarise Nolan’s desired standards for public life, we might note that many of our institutions, including those which claim the category of religious, seem to work in a Nolan denying manner. Without naming any particular individuals or occasions, I was shocked to discover, some time ago, that in the world of safeguarding the church institution has recourse, on occasion, to blatant dishonesty. Whether this is being noted in the current Wilkinson review I make no claim, since the document was not available to me when writing this piece. What I can say is that in the past, senior church people have been prepared to lie in a public interview or in the context of a legal enquiry. Sometimes the corruption of truth could possibly be the result of a genuine mistake. If that were to be the case, we would hope that the false statement would be admitted and corrected as quickly as possible. When there is no attempt to correct wrong or false information, it remains on the public record. Its capacity to cause damage to the church institution is there for ever. A real act of remorse and an open acknowledgement of truth failure might persuade a watching public to feel some sympathy for the one making an error or mistake in falsely representing facts. But the platitudinous expressions of regret uttered by senior bishops, but probably written by publicity professionals, do not rebuild trust. It so often seems that the individual speaking the words of regret is using a book full of sanitised words and expressions where all real meaning has been removed. The church lawyers seem to do one part of the cleaning while the other part is undertaken by communication experts who work closely with them.

The moment that a large organisation allows a single lie to be told by one of its representatives or top leaders and that lie is not later owned up to, any pretence of holding on firmly to the Nolan principles has been abandoned. Honesty is apparently no longer thought to be worth fighting for and so the integrity of all leaders is automatically called into question. Ordinary members of the church desperately want to believe that behaving honourably on the part of leaders is an important part of their witness to other church members and to the wider public. It is extremely disheartening to discover that the church establishment has become so careless of upholding the highest standards of honesty and integrity.

Why do people lie or bury the truth on behalf of organisations that they represent or lead? I asked myself why it could ever be worth lying about something in a church context. Two immediate reasons for telling such a lie occur to me. One is that the individual has been caught out in some serious failure to act or, worse still, some malfeasance. The lie is a desperate attempt to fend off the guilt. A second reason for lying is the attempt to defend, not oneself, but the institution to which one belongs, and in which the person repeating a falsehood may hold a position of high responsibility. If one does hold a status or position of power in any organisation, then one is going to do everything possible to defend it. One’s own self-esteem and professional identity is at stake and the integrity of the organisation as a whole is needed to retain one’s own personal reputation and standing.

In recent months and years, especially since the IICSA hearings, all the shenanigans at Christ Church, General Synod and the collapse of the ISB, we have devastatingly become inured to the variety of ways in which the church and its officers have not always observed the highest levels of honesty. Because this has been the case, I am hoping the imminent report of Sarah Wilkinson and that of Alexis Jay will insist on proper independence and ethical professionalism for the safeguarding activities of the Church. It may be that these two investigators will suggest to the church that the Nolan principles would be a good ethical foundation for the Church of England to follow. Surely these two ethical principles, honesty and integrity, can be expected of an organisation that gives a high priority to such values.

Returning to the other five Nolan principles, the one that leaps out for me is openness. It brings to mind a shameful episode in the sorry tale in the history of CofE safeguarding in 2017. In that year the Daily Telegraph revealed the existence of a secret document containing legal advice. This warned bishops not to give any apology to survivors in case that might increase liability for the church. This information was completely wrong both morally and from a legal perspective. The Compensation Act of 2006 reiterates older guidance which specifically excluded this legal understanding about apologies. Extra liability is not triggered by making apologies or offering pastoral support. The unnecessary suffering caused to survivors (and to the bishops themselves) over the years caused by this poor legal advice does not bear thinking about. This advice over apologies had been marked ‘strictly confidential’ so there had been little opportunity for anyone to know about it, let alone challenge it. Once again, a Nolan principle, here openness, was denied because of institutional fear and defensiveness. This lack of institutional openness has also been noted in the final Hillsborough report.

We have given space so far to noting how the CofE fails in three of the seven Nolan principles. A longer post could no doubt find examples of failure in all seven categories. Here we will pause briefly to consider the important principle of adequate leadership. All observers of the safeguarding scene have noticed repeatedly how the church safeguarding institutions seem to lack firm guidance and direction. Bishops seem terrified of being confronted by safeguarding queries. It appears that what direction there exists in the Church of England on safeguarding is decided, not by bishops, but by lawyers and senior lay bureaucrats. A close reading of the comments that are made following the Wilkinson Review will probably indicate that compassionate episcopal leadership has been almost completely absent as the church has tried to find ways to help us all move forward to repair and heal the sorry confusion that the CofE currently finds itself in the realm of safeguarding.

Revisiting the Nolan principles in relation to the church has not been a salutary experience for those of us who are members and still want to support the CofE. It is hard to feel optimistic when we have suggested that in four out seven categories, the church is definitely in the ‘unsatisfactory’ section. It seems unlikely that the remaining three categories would achieve anything much better. All the Nolan principles are linked, and failure in one area is likely to result in failure in the others.

Once an organisation starts to breach these principles, it first becomes a slippery slope and then an avalanche since each breach seems more trivial compared to the past.

These principles are all fundamentally Christian but in 60 years I have seen them all broken, indeed, shattered at every level from Parish to the Archbishops.

Cover-up can turn cock-up into conspiracy.

Soon it becomes part of the DNA of the organisation and no longer seems wrong.

When you get to this point, it can take a clearing out of the whole organisation to set things right again.

His Holiness Pope Francis is trying in the Vatican. I wonder if the C of E has the moral courage to copy the Roman Catholics.

Honesty has been a treasured value to me. So on various occasions, when it has been suggested that I should lie, it’s been a bit of a shock.

Once a sales executive was trying to persuade me to buy some advertising space on mainstream media. Hoping to impress his assistant perhaps, he started offering some unsolicited sales coaching. “Take a leaf out of my book, Steve: Lie.”

It took me back a bit, but obviously I could then be perfectly sure he was lying to me, to some extent.

On another occasion,at a job interview, the potential employer asked me cheekily if I could go behind the back of the recruitment agent (charging 30% first years salary) and save him their fee, explaining that “he was a capitalist”. Our code in the Institute of Chartered Accountants contains the requisite “Integrity”, but this seemed to have passed him by.

You expect this in business of course, but still the illogicality of it surprises me. How can we know if anything we say to each other is actually true when we agree to lie.

But dishonesty in the Church is even more disturbing. A Christian recently suggested I lie to someone I really care about. It was the brazen quality of the suggestion, and the bizarre pride that it carried, it being such an original idea and why hadn’t I been quick enough to think of it myself. Truly this is ludicrous. Our community will break down completely if we can’t get a grip on honesty.

Unfortunately I sense that speaking falsely is pandemic.

One of the additional features of some Church people in particular, and I grew up with this, is to have difficulty being honest with ourselves. Many writers have explored divisions or splits in the personality. Heinz Kohut springs to mind as a relatively comprehensible author. But in short we are quite capable of keeping parts of ourselves secret from our other parts. A pastor lives outwardly as a man of God, but his private life indicates a string of improper relationships. He sees no conflict, but avoids questions from those who get too close. Literally he doesn’t want to know what he’s like.

Leadership seems to attract characters like this. They are able to rise through the ranks adept at compromising, as they do this with themselves.

Honesty is perhaps easier when our groups are smaller and there is no convoluted hierarchy hindering transparency. Maybe the Church was never meant to be this big.

A profound piece, thank you Stephen.

The sentence that particularly resonates with me is: ‘Bishops seem terrified of being confronted by safeguarding queries’.

I have made very strong appeals to two Bishops and a Dean for compassion for the respondent. All three have refused saying they are not allowed to intervene in decisions made by the Safeguarding Core Group. A Bishop said recently, ‘I am not in a position to override the advice I have been given,’ [he was referring to a discussion he had with the Diocesan Safeguarding Teamabout the case].

How and why has the hierarchy in the Church of England lost all authority and become subservient to these Diocesan Safeguarding Groups who, after all, are a seemingly random group of people making legal decisions without any legal authority?

Certainly there seems to be no Christian influence in the actions of any of them, clergy or safeguarding.

I should have said, ‘Respondent wrongly accused and all evidence to prove this but no independent investigation to scrutinise this evidence’.

Completely off topic. I just popped in to say Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to everyone. Especially Stephen and Frances.

And to you English Athena. I’ve missed your regular contributions. Steve

Thank you. I got a real knock after my hip replacement. I’ve just done less, and I’ve been the better for it. But it’s a bit frustrating. And I’m still waiting for the second one!