I am sure that many of us can remember important conversations we have had which made possible significant changes of direction in our lives. I can remember one such conversation which took place in the early 80s. Those who have read this blog over a period will know that, long ago, I completed a university thesis connected with my interest in the Greek Orthodox liturgy. The detail of this research is unimportant here. However, there was a dilemma I faced that comes with getting involved with any information of a very specialised kind. This will be familiar to any of my readers who have undertaken post-graduate research. The problem in essence is this. Unless you are able to pursue a career of academic research and teaching, the information gathered over two or three years of academic research becomes rapidly out of date, especially if one has no access to university libraries. What does one do with research which may be of interest to only a handful of people who happen to be interested in your chosen topic? Was it all a massive waste of time to get so involved in a single specialised area of knowledge?

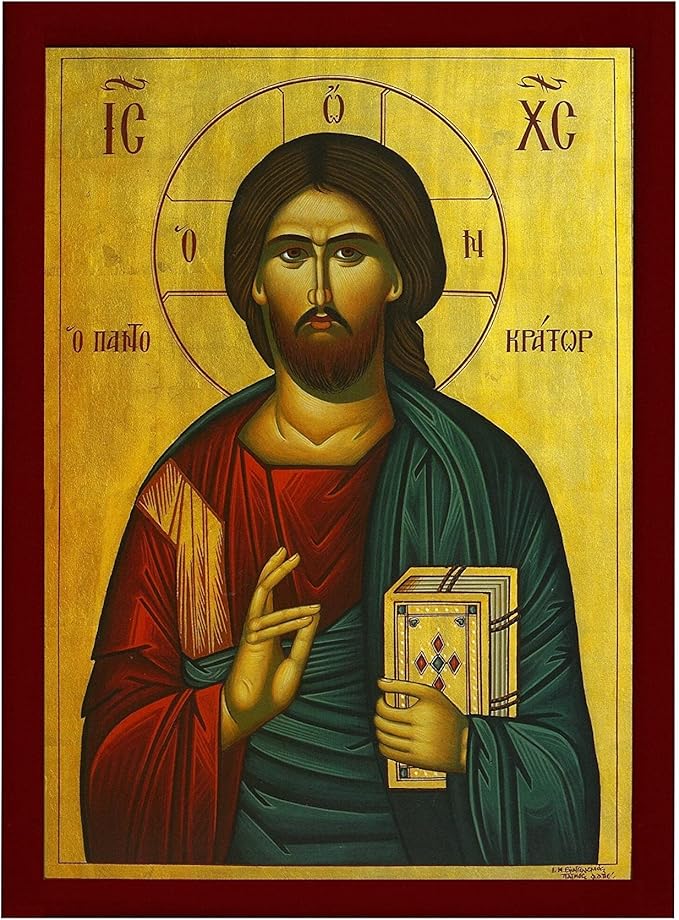

The conversation I had was with a distinguished academic who understood both the substance of my research and the dilemma of my being unable to take it further. What she said to me at the end of our conversation was a moment of liberation. I had described to her my then fairly recent interest in healing and the way that this dimension of activity seemed to embrace almost every Christian culture that was around at the time. I was meeting it in a New Age context right across to the charismatic. My academic mentor was interested in this exploration and made a fascinating observation. She pointed out that I, in the process of absorbing the highly visual culture of the Byzantine Orthodox faith, had also developed a facility to penetrate other value systems and cultures. Struggling to understand the assumptions of the Byzantine writers for two years had been, effectually, an initiation into thinking within an alien culture. This ability to live inside another culture in this way had demanded skills of imagination and intellectual flexibility which would always be useful. My new interest in Christian healing would draw on these same skills of understanding, imagination and flexibility of thought. In summary, my academic research had prepared me for an immersion into Christian cultures that were not my own. The word I use to describe this process is rather an old-fashioned one, the word ‘indwell’. One tries to live inside the thinking of another in order to understand better what the other is experiencing and talking about, while not necessarily agreeing with them. Indwelling the culture and thinking of other Christians has become a core activity of mine over the past 40 years.

The attempts, on my part, to indwell other people’s thinking have been partly successful in my professional work as a clergyman. For a time in the 80s I acted as an ecumenical officer for a diocese when the possibility of achieving Christianity unity seemed an achievable goal. My later work as a part-time adviser on the healing ministry was also undertaken with a background of a substantial generosity of spirit between Christians from quite different backgrounds. The emergence of a spirit of division and intolerance among Christians which seems to be a feature of this present century, is reflected in the current bitter disputes among Christian bodies who cannot agree on same-sex relationships. The deeper issue is that Christians fail to understand one another or agree how to read and understand the Bible. And it is on this point that my own skills and ability to indwell the thinking of others seems to fail.

‘Bible-believing Christians’ present us with a model of truth which allows no compromise. The problem I have with this group is not the tenets of their belief system which are in continuity with certain beliefs from the past. My problem is the way that the word ‘true’ in the context of the Bible is defined. When the word ‘infallible’ is also introduced into the discussion, I desperately feel a sense of shutters coming down, precluding anything resembling true dialogue. It is only since the eighteenth century that ideas of truth and falsehood in the scientific sense have been circulating. The definitions of truth that existed before had to accord with the dictates of those in spiritual or political power, not in the language of scientific reasoning. The contortions that some biblical ‘scholars’ get into to accommodate the ‘plain meaning’ of God’s Word when reading the text of Genesis are tortuous and insulting to anyone of basic intelligence. Answers to simple questions are needed – how did the creation of sun and moon take place after the creation of light in the Genesis narrative? What were the numbers of animals entering the Ark? These questions cannot be answered with the pseudo-scientific formulae of many Biblical conservatives. The answers that exist in reasonable discourse belong to the world of symbol and metaphor not scientific measurement. I recognise that few Christian teachers in the UK spend much time on these questions. In the scheme of things, they are trivial. More important is the possibility that ordinary Christians, reared to accept ideas of scriptural infallibility, secretly spend a great deal of time worrying about such issues. Only allowed to have a single version of the meaning of truth, these Christians are deprived of any insight as to how things can be true in a whole number of ways that are more glorious, more life enhancing than a narrow concentration on scientific fact. One quotation from Scripture draws us back to the richness of beauty in our understanding of God ‘O worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness’. The truth encountered in beauty takes precedence over the truth contained formulaic barely understood doctrinal formulae. The latter matter but they never engage the human spirit without the former.

To return to my important conversation with my academic mentor, which had the effect of releasing my imagination and my aesthetic sensitivity into my spiritual and intellectual journey, I am grateful for one special gift. I am deeply grateful for the fact that in my reading, learning and discussions over the years I have never been encouraged to think I have arrived, in respect of truth. The discovery of aspects of truth on this journey only urges me on further to explore new things. Paradoxically the more of truth one learns, the more truth yet to be discovered emerges.

Interesting thoughts! Thanks. I suppose understanding other traditions is often about becoming inwardly aware of one’s own hidden cultural genesis, or DNA and prejudices or slants. For low Church Anglicans (and for Presbyterians) there can be a magical appreciation of language and logic. But art and imagery-in earlier years at least-is often a neglected zone.

Is the inflexible use of the bible, by a dogmatic and authoritarian leader, implicated in some evangelical scandals or their cover up? The idea of astronomers, geologists or biologists, all being blinded into wrong discoveries (or beliefs), makes little sense to me. Yet some v sincere YEC people exist, and believe literally everything in the OT.

Starting life with doctrinal certainty, I had no initial reason to doubt anything. However the inconsistencies and hypocrisy seemed to grow over time.

In search of joy, which was lacking despite being proclaimed as present, I ventured similarly into areas of our faith that included the possibility of healing, for example. Being open to some things, can progress to being able to allow almost ANYTHING to go, and this manifestly wasn’t safe either. In some quarters any ideas proclaimed from the hot spot at centre, have the status of absolute truth, particularly if they’ve derived from the lips of a so-called apostle. There seem to rather a lot of these.

As I grow much older I’m more comfortable with not (quite) knowing. And the more I study, the more I realise I don’t know.

Indeed, yes, wise sentiments!

Pick up a Bible and automatically become a cosmologist. Study the scriptures deeply and you also become an expert on psychology and law etc..etc…etc…

Messianic style megalomania, in fallen charismatic-evangelical leaders, resembles the Jehovah’s Witness tactic of ending a conversation with “We have the truth”.

Perhaps the truth of what underlies a lot of adult and child ill-treatment Church cover-ups is far less complex than most of us once imagined.

The “well-enough oiled P-A (pseudo-apostle)” ( I avoid the word anointed) can try to ignore many things or people: national law, Church rules, rules of confidentiality, biblical principles of natural justice, conventional health protection wisdom, the professional expertise of education experts, concerned whistleblowers or witnesses.

And the P-A dismisses anyone who complains as a satanic “troublemaker”. And when it all comes out in the wash-then it’s a “hostile and unforgiving media” or a “ruthless legal process of justice”-or “a lack of loyalty in Church members”.

Is DARVO (Deny-Attack-Reverse Victim-and-Offender) getting exposed on an ever bigger scale? House of Survivors website is a great resource to read or share.

‘Being open to some things, can progress to being able to allow almost ANYTHING to go, and this manifestly wasn’t safe either.’

‘The point of opening your mind, as of opening your mouth, is to close it again on something solid.’ I think that was C.S. Lewis quoting G.K. Chesterton.

W Barclay’s commentary on 1 Corinthians has an interesting initial section on Chapter 14. Maybe shed light on some of the egotistical and authoritarian horrors seen in elements of the Church?

We sometimes seem to lose our critical faculties, especially when a charismatic leader, or a Charismatic leader says stuff.

Hard to get the balance between ‘reason’ and ’emotion’ right (privately and in the Church). Learning by mistakes is painful at times. First Corinthians catches my eye (especially Chapter 14): Order vs spontaneity in Church is a hard topic.

Thank you, Stephen for your thoughts which reflect some of my own, but you express them at a deeper level than I can.

Questions -we learn through asking questions, thinking about things and challenging possibly narrow assumptions, but that won’t make us popular with those who demand we stick with them. For years now I’ve considered that (for example) there is no inherent contradiction between Genesis 1&2 etc and the scientific view of how things began. Essentially they are totally different disciplines which complement, rather than contradict each other. The problem is with those, on both sides, who insist solely on their view being heard, or held.

Same with the same sex debate – how many Christians have I met who simply say ‘a gay can’t be a Christian.’ Why not? God made us all, and accepts us as we are. You might just as well say that a heterosexual can’t be a Christian – but they find ways of wriggling round that one! The rest of the issue, to a large degree, is a matter of opinion and interpretation – but you have to be willing to step outside the parameters of the Bible alone and accept understanding from other sources; science, medicine and psychology for example.

Unfortunately in the past I’ve known plenty of Christians who wouldn’t do that – and suspect there are a great many more now. ‘True’ has come to mean ‘rational’, ‘definable’, ‘set in stone’ or ‘measured with a slide rule’; faith in turn has become, for many, a set of mathematical equations or scientific formulae which must not be deviated from. Where is the mystery, the sense of awe and wonder in the divine which cannot be reduced to the tangible and material? Truly, as Kenneth Graham said, we no longer expect to meet ‘angels unawares’ and are truly the poorer for it.

Good example – the advice to take ‘the clear, obvious, or simple meaning of scripture’ is by and large a good one – but in which language? English – or the original Hebrew or Greek? And who do you trust if you can’t read either of those two? I know plenty of people who won’t accept that much cherished ‘proof texts’, on matters such as headship or SSM may not mean quite the same in their original language, or indeed their original social context. When does certainty step overboard into arrogance?

Part of the problem is, I fear, the entrenched evangelical mindset which sees the world and society around us as a threat, an enemy to the little lifeboat of ‘true believers’, and runs away from anything that might disturb it. Yet we’re called to live in that same world, to be witnesses to Christ’s light, life and love. How can they do that from within their stone-walled defensive laager?

Having experienced the freedom of worship, tolerance and acceptance of differing views which the early renewal movement championed, I found the superseding growth of rigid dogmatism, about both doctrine, God and life, heart breaking. It was an almost total denial of everything attractive that had gone before – and sadly I still find echoes of its intolerance lurking within my own heart even now. ‘Certainty’ is the biggest enemy to true, trusting faith that I can think of.

We cannot reduce the promised ‘life in all its fullness’ to a series of dogmas, dry, dusty academic formulae, as so much evangelical thinking seems to do, and then expect people to embrace it. They want something more than the mundane from life – and, no, we can’t always experience that in material terms. Nor, I think, should we promise too much of the experiential side of the spiritual realm – it isn’t within our control, and people experience it differently anyway. (Is there a possibility that Jesus’ promise, that our joy may be full, will only be completely experienced in the eternal world? Too few people seem to recognise the reality of ‘nearly, yes, but not fully yet’. It keeps haunting me, for certain.)

We walk a living tightrope balancing between the two camps of faith and reality. There is a lot of wisdom in Father Brown’s comment, that it pays to read other people’s Bibles besides our own.

Well said.

Thank you Stephen for this article and for the comments that are all very relevant.l always found that what the ‘church’ taught so definitively had little to do with what I held dear in my heart.