The Epic Fight to Survive Goes to the Wire

By Nick Craven, Sports Correspondent

Head coach Justn Welby

Assistant Coach Steve Cottrell

Club Motto: Nil Satis Nisi Optimum (“nothing but the best”)

Club Colours: Purple top, shorts and socks (home). Away kit: Post Office Bright Red (Farrow and Ball shade: Angry and Embarrassed).

Club Mascot: Willie Nye and his Crook; a white ferret with an episcopal staff.

Club Chairman and Sole Owner: William Nye esq.

Club Sponsor: Elf-and-Safeguarding

(Our Vision: “Leading Providers of Unctuous Emulsion for the Broken”.)

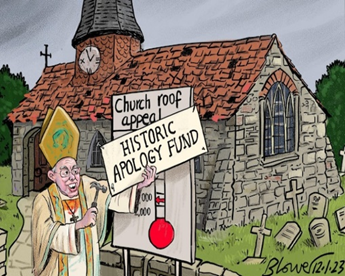

Languishing in the relegation zone of National League Two, this once great Premier League football team of Lambeth Palace FC playing under the twin towers is struggling with performance, team morale, protests from fans and regular scandals.

After a run of very poor results Justin Welby has resigned as manager, to be replaced by assistant coach Steve Cottrell who is now stepping up as caretaker manager. Once again, every fortnight our ace reporter, Gaby Lippy, brings us an exclusive post-match interview. This is a story of a Club in steep decline, but still aiming for the top!

Episode Eight: Cottrell-in-Charge (This Week)

Gaby: Well Steve, here you are, now the Caretaker Manager. Top Job, eh? But what are your thoughts on the manner of Welby’s departure? I mean football can be a funny old game, can’t it? And quite brutal, don’t you think?

Steve: Well Gaby, as you say, that’s football, isn’t it? I do feel for Justin. I mean Lambeth Palace FC have had a long, long streak of dreadful luck, and to be honest, we’ve not had the best refs in the world. Some of the decisions against us have been absolute shockers, and games where we should have drawn and gone to a replay and kept going with those replays over several seasons, have been unfairly wound up with penalty shootouts.

I mean the Safeguarding Challenge Cup isn’t supposed to end now – it is meant to be played out in local and regional leagues over several seasons, before it comes back to Championship and Premiership level, before going back out into the regions again. It is not supposed to be settled over a couple of matches.

Gaby: I see, yes. I presume you are referring to the ISB-11 here, who you kept avoiding having to play a match with, and in the end, the fixture and the points were eventually awarded to them? You also lost badly against Jay United, Wilkinson Wanderers, and Glasgow Gladiators (though you claim you didn’t field a full team for that game). But the manner of your defeat against Makin Rovers was the worst defeat in the club’s history, if not all footballing history. I mean, the list goes on, doesn’t it? These were thumping, heavy defeats. They were humiliating losses, weren’t they?

Steve: Ooh, I think “humiliating” is a bit strong, Gaby. They’ve certainly given us some pause for thought. Well, as Assistant Coach, I’ve kept saying to the lads that the art of winning matches is to score goals and not concede more goals than we score. We’re working on that every day, and the lads spend a lot of their time on VAR doing the lessons-learned reviews. The fans know how hard this is for us.

Gaby: Well, it might be hard for the team, but its much harder being a fan or a season ticket holder. They pay pay good money to watch this, and they’re not happy. Now, Welby’s gone after 15,000 fans signed a petition for his removal, and there were banners calling for him to be sacked. But Steve, the tactics for these games were yours too, weren’t they? I mean you prepped the team, coached the players, and surely you must share the blame just as much as Welby here. Shouldn’t you do the decent thing and resign too? I mean a new manager coming in won’t want you anyway, will they? You’re toast, surely?

Steve: Gaby, I am just going to be the Caretaker Manager here. The Head Coach job is probably not for me. But football is a funny old game, and you never know how it will turn out. So I’ve said to the Chairman, Willie Nye, that I’ll stay on as long as he wants, and if the results improve in the next six months, then who knows, I might get the job full-time.

Gaby: Would you want that?

Steve: Oooh, Gaby, that’s not for me to say, is it? It’s Willie’s pick, and of course, the fans have a bit of a say, too, in confirming Willie’s choice. Let’s just say that if we turn things around in the next few months, re-stock the trophy cabinet with some silverware, play some entertaining football, we can review our options then. I rule nothing out. Or in. I rule nothing is what I mean, I think. Is it, er…hang on…

Gaby: Right, can we talk about morale in the dressing room? You’ve put Hartley up on a free transfer now, as Hartley claimed that Welby’s run of form was so poor his position had become untenable. It’s a bit petty and vindictive to punish one of your youngest players like this, isn’t it?

Steve: Right, well I need to say a few things back here in response to that tough line of questioning.

First, loyalty is obviously the most important thing a club needs from its players. It matters more than skill, proficiency, integrity, winning, goals…anything, really. Also, we have a zero-tolerance policy on dissent. That’s why we’ve handed Hartley a free transfer. Uzbekistan has a fantastic league, and it will be a great place for Hartley to re-learn the basics of football, beginning with loyalty. North Korea is also an option.

Second, Welby was very hot on discipline, and any dissent would often be punished with having your wages docked, so I think Hartley has got off lightly here. Welby ran a tight squad, and he didn’t like the players to express themselves too much, or even at all. If you played out of position or said something off the field he didn’t like, you’d be packing your bags. He was very strict…but he kept discipline, and that was a plus. Until it failed.

Third, we just can’t have fans, players and referees telling us how to play the game. That’s not right, because as Head Coach I’m in charge of the games and the results. The Chairman of the Board, Willie Nye, has always said that what counts most is results. And when the results don’t go your way, you need to be in a position to explain why those results didn’t really count in the first place. That’s football, and that way, we never lose.

Gaby: Seriously…?

Steve: Oh yes, it’s all about a united front. If discipline and order have broken down in the dressing room, then you clear out the dressing room. The players know that. That’s why you never hear them speak out about anything. The players need to be occasionally reminded that loyalty comes first. No matter how bad the results, we expect everyone to pull together, stand behind the manager, and accept his version of what happened in the game. That’s the way leagues are won.

We can’t have dissension in the team, and players or fans coming up with different readings of the games. It’s bad enough having to put up with independent referees. We should never have agreed to that. Back in the good old days, if we were playing at home, we provided the referees ourselves and ran the VAR and the linesman. And in those days we always played at home too. So we got independent refs that we paid for and employed, and who answered to the Chairman. That’s how it should be, really.

To be honest, it’s the same with the teams we play against like ISB-11. If the players are not registered with us, and subject to our club rules, then we don’t engage with that team, and don’t play them. We only play against teams who recognise that we are in charge, and we oversee the time and place of the match, and the result. If teams like ISB-11 can’t agree to simple things like, we will just ignore them, and we have every right to do so.

Gaby: …er right, I see. OK, now you’ve had this dreadful run of results of late, and some Big Games coming up. LLF Spartan Boys are next, and you’ve only ever lost to them heavily, but once managed a scrappy draw. How is this going to work?

Steve: I think we’ll be fine. Snow is our new tactics coach, and he also plays in goal and as a false nine. He’s a conservative player, but he likes to hang out on the right if he can. He’s comfortable there on and off the field. He’s not really a natural left-field player.

Gaby: Who are the left-field players left in the team?

Steve: Well, I’ll have to give you that’s a gap in the squad at the moment. Welby didn’t like them, really. They were too, well, individualistic. Anyway, not to worry, as Mr. Nye is currently off scalping potential talent.

Gaby: Don’t you mean scouting?

Steve: That’s what I just said.

Gaby: Well, we need to draw this interview to a close for now. In short, it’s been a disaster these past few years, hasn’t it? It’s been a truly dreadful run of results. Tons of money spent on lots of new players, some of whom don’t last very long. Lots of different ways of playing too, with no commitment to the basics. We’ve seen Fresh Expressions of Football come and go. We’ve had Talent Pipelines, Footie Hubs, and seen Pioneer Football come and go. Welby brought players in from the ACNA league in the USA who aren’t actually registered to play here. Then there’s the third-provincial team who want to play in their own league, but they want one-third of your stadium, a third of the club revenues and 33% of the rights on the shirt sales, logo and mascot, even though they’re a tiny minority (5%) of the fans?

Steve: Gaby, I promise the fans things will be different now under my watch. Just you wait and see. My results will speak for themselves. I will be judged on my results. I’ve said that to…er…

Gaby: OK, can we finally switch to a subject I know that is dear to you, namely women’s football? Now Lambeth Palace Ladies are going great guns, aren’t they? Top of the league, a record haul of goals, Golden Boot winner in the offing. But, Steve – and I have to ask you this – you have a few members of your Board who think women can’t play football…

Steve: Now hang on a moment…

Gaby: …no, don’t interrupt me. They say women can’t play football, and then they say, even if they do, it isn’t really football. They say – your Board Members and some of your players – that the ladies should stick to netball, serving half-time refreshments and maybe helping the team doctor with the magic sponge.

Steve: I don’t want to get into all that. Lambeth Palace is one big happy Football Club. It is a family, except for the players now up on the Lambeth (free transfer) List – did I mention them earlier, like Hartley? Apart from that, Lambeth Palace welcomes everyone, and we treat everyone equally, whatever they do.

We have a proud record on this. We were the first major team to have a black lad up front playing in the box in the 1970s. But we also kept our junior KKK white-boys-only team going until 1975 too. I mean that inclusivity tells you everything you need to know about this club. We’re completely undiscriminating.

Gaby: Did you mean to say ‘non-discriminatory’?

Steve: Yes, exactly – undiscerning. That’s what I just said. Is there actually any difference?

Gaby: Steve Cottrell, thank you very much. Back to you in the studio, Gary.