It has become difficult to know how to respond to yet more stories of scandal in the Church of England. My readers will know all about the ‘Liverpool affair’ by the time this blog appears, so I do not need to recount all the allegations and denials that have appeared in the Press and elsewhere over the past couple of days. The blog wants to focus, not on the details of the possible sexual harassments perpetrated by a diocesan bishop, but on some of the ways that stories like this are deeply harmful, even ruinous, for the morale of the national Church, not to mention its reputation.

At this moment, the allegations of misconduct against Bishop Perumbalath have not been proven, though there is an implied acceptance of some degree of wrongdoing indicated by the fact of the bishop’s resignation announcement. Even before his position as bishop became impossible to support, in the face of widespread pressure from his senior colleagues in the diocese, it was unfortunate, to say the least, to read the bishop’s name in the same sentences as allegation, police caution and harassment. The whole sequence of events will need to be thoroughly investigated since the Channel 4 reports raise as many concerns over the Church response to the affair as they do from the allegations by the two women involved. In short, a resignation should not allow the details of suspected abuses to remain buried. I am sure I speak for many when I say that the saga raises numerous questions about safeguarding professionalism, appointment processes, people skills and serious failings of management in the wider C/E.

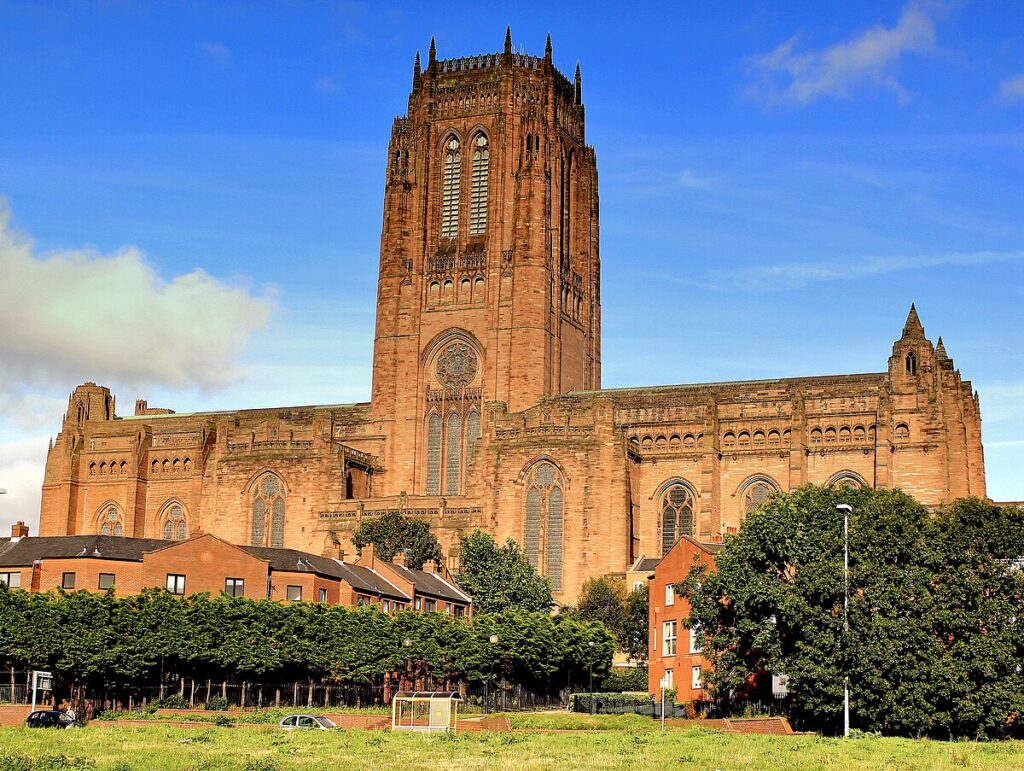

It is important to note that a diocesan bishop sits over a large organisation, like the Liverpool Diocese, and has a relationship with many people. This will involve having an enormous amount of trust placed in him/her. Any deviation from a meticulous observing of the boundaries that properly belong to the ethical ordering of church relationships, will probably be a cause of serious harm. The higher up the hierarchy that such an abusive event takes place, the greater the harm. Just as a local parish priest sets an example and the tone for the ordering of good harmonious relationships within his/her parish, so a bishop sets an example for an entire diocese. It is not unreasonable for clergy to want to project on to the person in charge and see them as a model for their ministry. At the service of induction to a parish, the bishop formally delegates his/her authority to the new incumbent. In effect the authority he/she exercises in the parish is episcopal in nature. Authority is flowing in two directions. It matters greatly to the authorising bishop that the parish priest is competent and honest, just as it matters to the priest that the bishop is a person of utter integrity.

The ’Liverpool affair’ is a matter of far more importance that just a determination of the motivation of one individual in authority and whether they did or did not stray into abusive behaviour. It is about the damage to tendons of trust that hold together and connect a fragile human organisation, which is here a diocese of the C/E. When I was ordained some 54 years ago, I had a sense of committing myself to God while committing myself to a human institution we call Church. The existence of holier, more intelligent and wiser priests in this body across the country meant that my own limitations were less crucial than if I had been attempting to do the job all on my own. Of course, the clergy look to the Holy Spirit for guidance and help to do their task of teaching and caring; they also find themselves looking to other clergy to encourage them whether through chance meeting or reading material written in books or on the internet. Ministry is individual but it is also in an important sense corporate. We need the clergy we look up to and admire to have the solid reliability that we associate with the word integrity. It really matters to each of us and our individual ministries when the honesty and just dealing of one of our number is questioned or challenged in some way.

It matters very much indeed to the clergy and people of the Diocese of Liverpool that the issues concerning their now former bishop are fully investigated and dealt with in the best possible way. It is also of concern to the rest of us, not only in Liverpool, that the truth of what has happened is known and responded to without some kind of cover-up. The truth is what enables the people of God to look forward to the future work of the Church in Liverpool and elsewhere. Part of the future will depend on how well we have faced up to and dealt with the past. In spite of rules created by the church, that reckon that one year is sufficient time to process an episode of sexual harassment, the reality is that the legacy of abusive behaviour currently weighs heavily on the C/E and the institution can never be whole until it is dealt with. Many people in the Church would love it if a page could be turned and a new beginning declared. That might be possible if it were just a matter of dealing with the sin and frailty of human offenders. The problem, shown in stark outline by the current episode, is that human frailty is not only in the abuse perpetrators but also inside the systems that the Church operates. There are found to be, on every occasion when a major scandal breaks, archaic processes that are unfit for purpose. Does anyone really believe today that the requirement to launch a complaint within a year of an alleged offence always serves justice? The ‘professionals’ in the NST, in the offices of church lawyers overseeing safeguarding and the secret committees choosing bishops, must all allow their judgements to be scrutinised. When appointments are made to posts where candidates can, if left their own devices, do potentially great harm, this should be a moment for forensic questioning. Sorting out not only malfeasance by church people, but also checking abuse that is made possible by inadequate processes is a huge task, but it must be undertaken.

The Liverpool affair will probably be lost to the memories of the vast majority of those who are currently shocked and dismayed by what it suggests about the C/E. For those who do remember anything of the allegations in ten years’ time, the memory will be as much about the confused and muddled response to the allegations, with its constant appeal to process than the actual details of the claimed assaults. The response to every scandal is an appeal to ‘learn lessons’. If we were really learning lessons, somehow one feels that the response to the Liverpool affair would have been far better than it is so far. Is there even a small hope that things will be better this time?