It has become difficult to know how to respond to yet more stories of scandal in the Church of England. My readers will know all about the ‘Liverpool affair’ by the time this blog appears, so I do not need to recount all the allegations and denials that have appeared in the Press and elsewhere over the past couple of days. The blog wants to focus, not on the details of the possible sexual harassments perpetrated by a diocesan bishop, but on some of the ways that stories like this are deeply harmful, even ruinous, for the morale of the national Church, not to mention its reputation.

At this moment, the allegations of misconduct against Bishop Perumbalath have not been proven, though there is an implied acceptance of some degree of wrongdoing indicated by the fact of the bishop’s resignation announcement. Even before his position as bishop became impossible to support, in the face of widespread pressure from his senior colleagues in the diocese, it was unfortunate, to say the least, to read the bishop’s name in the same sentences as allegation, police caution and harassment. The whole sequence of events will need to be thoroughly investigated since the Channel 4 reports raise as many concerns over the Church response to the affair as they do from the allegations by the two women involved. In short, a resignation should not allow the details of suspected abuses to remain buried. I am sure I speak for many when I say that the saga raises numerous questions about safeguarding professionalism, appointment processes, people skills and serious failings of management in the wider C/E.

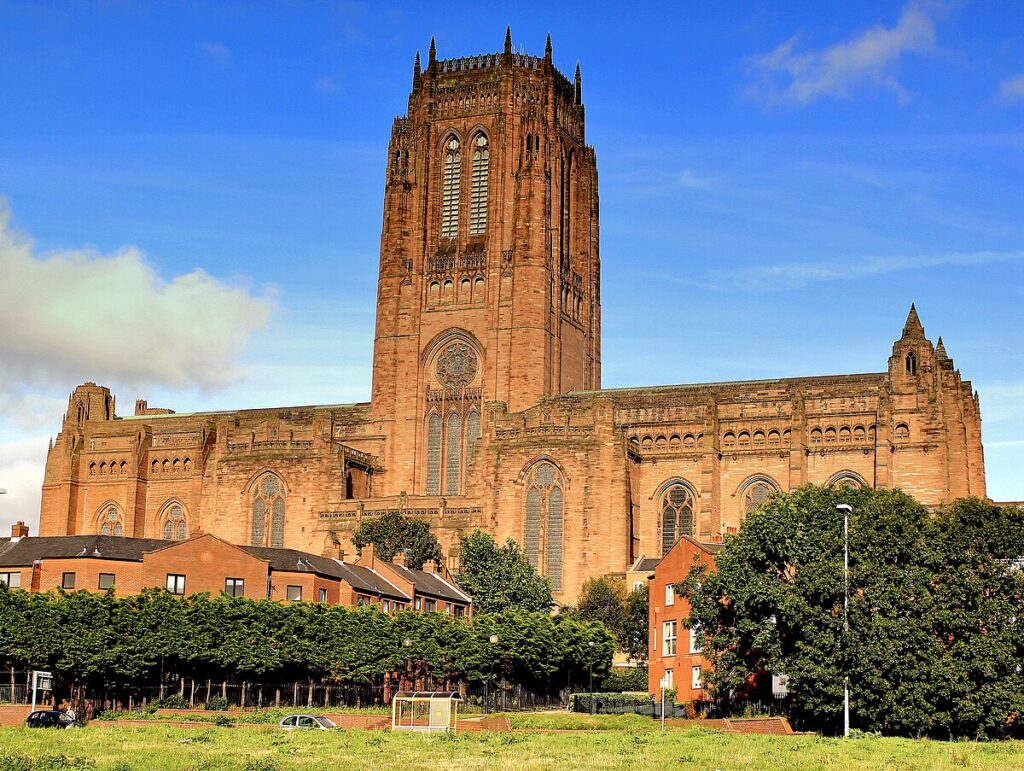

It is important to note that a diocesan bishop sits over a large organisation, like the Liverpool Diocese, and has a relationship with many people. This will involve having an enormous amount of trust placed in him/her. Any deviation from a meticulous observing of the boundaries that properly belong to the ethical ordering of church relationships, will probably be a cause of serious harm. The higher up the hierarchy that such an abusive event takes place, the greater the harm. Just as a local parish priest sets an example and the tone for the ordering of good harmonious relationships within his/her parish, so a bishop sets an example for an entire diocese. It is not unreasonable for clergy to want to project on to the person in charge and see them as a model for their ministry. At the service of induction to a parish, the bishop formally delegates his/her authority to the new incumbent. In effect the authority he/she exercises in the parish is episcopal in nature. Authority is flowing in two directions. It matters greatly to the authorising bishop that the parish priest is competent and honest, just as it matters to the priest that the bishop is a person of utter integrity.

The ’Liverpool affair’ is a matter of far more importance that just a determination of the motivation of one individual in authority and whether they did or did not stray into abusive behaviour. It is about the damage to tendons of trust that hold together and connect a fragile human organisation, which is here a diocese of the C/E. When I was ordained some 54 years ago, I had a sense of committing myself to God while committing myself to a human institution we call Church. The existence of holier, more intelligent and wiser priests in this body across the country meant that my own limitations were less crucial than if I had been attempting to do the job all on my own. Of course, the clergy look to the Holy Spirit for guidance and help to do their task of teaching and caring; they also find themselves looking to other clergy to encourage them whether through chance meeting or reading material written in books or on the internet. Ministry is individual but it is also in an important sense corporate. We need the clergy we look up to and admire to have the solid reliability that we associate with the word integrity. It really matters to each of us and our individual ministries when the honesty and just dealing of one of our number is questioned or challenged in some way.

It matters very much indeed to the clergy and people of the Diocese of Liverpool that the issues concerning their now former bishop are fully investigated and dealt with in the best possible way. It is also of concern to the rest of us, not only in Liverpool, that the truth of what has happened is known and responded to without some kind of cover-up. The truth is what enables the people of God to look forward to the future work of the Church in Liverpool and elsewhere. Part of the future will depend on how well we have faced up to and dealt with the past. In spite of rules created by the church, that reckon that one year is sufficient time to process an episode of sexual harassment, the reality is that the legacy of abusive behaviour currently weighs heavily on the C/E and the institution can never be whole until it is dealt with. Many people in the Church would love it if a page could be turned and a new beginning declared. That might be possible if it were just a matter of dealing with the sin and frailty of human offenders. The problem, shown in stark outline by the current episode, is that human frailty is not only in the abuse perpetrators but also inside the systems that the Church operates. There are found to be, on every occasion when a major scandal breaks, archaic processes that are unfit for purpose. Does anyone really believe today that the requirement to launch a complaint within a year of an alleged offence always serves justice? The ‘professionals’ in the NST, in the offices of church lawyers overseeing safeguarding and the secret committees choosing bishops, must all allow their judgements to be scrutinised. When appointments are made to posts where candidates can, if left their own devices, do potentially great harm, this should be a moment for forensic questioning. Sorting out not only malfeasance by church people, but also checking abuse that is made possible by inadequate processes is a huge task, but it must be undertaken.

The Liverpool affair will probably be lost to the memories of the vast majority of those who are currently shocked and dismayed by what it suggests about the C/E. For those who do remember anything of the allegations in ten years’ time, the memory will be as much about the confused and muddled response to the allegations, with its constant appeal to process than the actual details of the claimed assaults. The response to every scandal is an appeal to ‘learn lessons’. If we were really learning lessons, somehow one feels that the response to the Liverpool affair would have been far better than it is so far. Is there even a small hope that things will be better this time?

Well done Stephen.

I remember being particularly impressed by the way you handled Martyn Percy’s issue.

Last time we met I mentioned a personal unease about the way these issues are handled in public. I’ve reflected on it, having spent 20 years in Liverpool. I never met Perumbalath so have no personal relationship with him.

1) When I studied Criminology, it became clear that the British penal system, like most Western ones, is designed not to reduce the crime rate (in most cases it increases it) but to provide the public with a succession of scapegoats to demonise.

2) The truth, about both what happened and what should be done about it, should be determined by a small number of people who know about the principles and find out about the people concerned. Decisions should not be based on how the general public, let alone the media, feels.

3) The sexual libido isn’t going to go away. It’s an essential feature of any species’ survival. Westerners love gossiping about other people’s sex lives, more than other cultures. This reflects western society’s being ill at ease with its sexuality. We have lots of taboos on what can be said, let alone done.

4) What could go away, but has been getting stronger and stronger for the last 50 years, is power inequalities. It’s part of our culture that English bishops get a lot more deference than Anglican bishops in the rest of the world. We can’t make powerful men tie a knot in their willies but we could reduce their power. Here lie more taboos. Discrimination against gays, blacks and women is openly criticised. Discrimination against the poor, starving and homeless isn’t. It’s what the chattering classes don’t want us to talk about because they benefit. Until we get a massive redistribution of power, and therefore wealth, things will only get worse. This would be political. Meanwhile we all prefer to talk about other people’s sex lives.

Your comment about Anglican bishops in England getting a lot more deference than Anglican bishops in other parts of the worsis not true. In cultures such as Nigeria (or indeed many other parts of Africa) the amount of deference accorded to bishops is something the English bishops could only long for!

Bishop Perumbalath was, at the beginning of his career, a vicar at All Saints Perry Street, Northfleet. I had been organist there but left before his time. But I heard that he created a lot of friction and unhappiness through his behaviour. Shame it wasn’t picked up then.

Second Corinthians 13:1 is the key which shines a light here. High profile scandals get headlines. But everyday exploitation, bullying or harassment do far more damage.

Diocesan Safeguarding will readily pass an issue on to the police. But the police must prove guilt ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. The CPS Crown Prosecution Service will demand a high chance of any potential charge sticking. Dioceses (or Bishops) can thus say-‘We passed this to the police’-but this can easily be just a ‘get out of jail card’: in perhaps more than one sense.

Why can an independent inquiry panel (perhaps of KC’s and/or Judges) not be immediately convened here, and give a summary verdict on the evidence gathered to date? What is the written witness evidence, from both the alleged (or potential) female victims, and what defence has been presented? It might be a bold and helpful move if the first witness went public!

Are ‘The Rules’, if they exist at all, perhaps very different for our Bishops? A junior cleric, business employee, factory worker or public sector employee would probably have the evidence against them looked at by senior leaders, then possibly be suspended pending an independent inquiry.

Anglicans now face a choice! Do we accept the nonsense on offer? Or do we demand radical and urgent change? Archbishop Cottrell’s goose is cooked, and he needs to get his bags packed without delay.

I note that it was Stephen Cottrell who appointed Perumbalath first an archdeacon, then a bishop in Chelmsford Diocese; and then (as Archbishop of York) oversaw his appointment as diocesan bishop of Liverpool. Was it Cottrell also who adjudicated the Bishop of Warrington’s complaint against the Bishop of Liverpool? Who decided that the best way forward was to place the suffragan ‘on leave’ for a whole 18 months, with no resolution of the matter in sight, while Perumbalath continued in his career and ministry unhindered? It seems, to say the least, very unfair on ‘Bishop Bev’, who has described that 18 months of not working, and not being able to tell people why, as excruciating. And all that after a prior complaint of serious sexual assault had been made in Chelmsford.

Once again-‘The Old Boy Bishop Club’-looks as if it is still protecting members. But has the presence of women in the House of Bishops made a huge difference for the better?

The female bishops have almost always been selected by men who opt for women who won’t rock the boat by doing things very differently. It’s always been like this when women are pioneering new roles. I don’t know how the Bishop of Newcastle got through, but she had been a bishop in New Zealand before coming back here.

In the USA, where bishops are elected, they seem more likely to choose outliers. The first American female bishop, Barbara Harris, was black and divorced, and quite outspoken. She would never have been selected by male bishops here.

Why was ‘Ms Warrington’ sidelined after testifying, yet ‘Mr Liverpool’ allowed to stay in post?

Yes! 2 Cor 13:1 sheds light!

The caste system again! Some people are just too important to be challenged. And we see it again in the news stories about Russell Brand. People said nothing because there didn’t seem to be any point. Or if someone is in favour, they are pushed forward, and that’s it. Do the powerful truly believe God is prompting them to behave like this? Or are these just human beings wanting to feel bigger? I’ve seen both. Even relatively small fish swimming in a small pond can do considerable harm in their own area.

‘Cabal’ maybe indicates the Anglican crisis better than ‘caste’. Very small cliques and groups run the show. Everyone else puts up, shuts up or just leaves. Second Corinthians 13:1 is turned on its head. A cabal can shun and ostracise people without the need for any witnesses. Yet can the cabal also ignore serial abuse by friends or allies?

I agree with what you are saying there. Cabales, which would be labelled by themselves as mere friendship groups, but operate with gossip and differing rules for outsiders and insiders, can be rife. Narcissism is a big problem in the church. It is usually fairly obvious in the prose people write, as a large percentage of the words ‘I’ and ‘me’ and ‘myself’ proliferate, and throw up red flags everywhere. The narcissists deliberately collect ‘flying monkeys’ and much mischief can be done…

It is fairly horrid when you know undermining gossip of an indeterminate nature is happening behind the scenes, and withstanding and continuing to serve, as I believe is usually the right thing, is tough. One of the things I had said by others about myself was that I might be gay, though I am and always have been very straight, and am married (and once only) with many children. This was, I think, partly because I don’t flirt, and partly through misplaced competition.

I only learnt months after the fact that my suspicions that this had been said were correct. So I sympathise with what you went through. Be of good cheer for you are not alone!

The church needs to get back to the 10 commandments, and Jesus’ extension of them. We have not yet got the basics operating, while people opine about secondary and tertiary issues ad nauseam!

Best wishes and prayers…

There’s a real problem with reporting things. Years ago I reported elements of grooming behaviour by the church youth leader. I reported to the church safeguarding officer who went to the team vicar in charge. He alerted the youth leader’s vicar and between them they started a campaign of harassment and bullying which lasted for more than 18 months and still has repercussions today. My children were banned from the youth club and I was told there was too much hate directed towards me for me to continue to go to the church. The vicar and youth leader held meetings with church members both publicly and privately where I was slandered by lies and deceit. When I asked the team vicar why he didn’t believe me he said it was because the youth leader was a paid member of church staff and I wasn’t. When I asked him why he didn’t try to stop the bullying he said ‘what do you expect? You’ve spoken against the youth leader’ The Bishop’s secretary refused to pass on an email to him and the diocesan safeguarding officer played no worthwhile role at all.

Kangaroo Court Justice defiles the Anglican Church. Experiences like the one you describe may be commonplace. Odd how the Bishop of Warrington went out of circulation for an extended time, yet the Bishop of Liverpool stayed put until Cathy Newman and Channel 4 shone a light on allegations of there being female victims. The words of 2 Cor 13:1 need to be shared and reflected upon when we consider serial failures by Anglican Bishops.

Were there any other potential victims-witnesses-whistleblowers in your situation? Also, it can be helpful to have someone with a legal background (or legal exposure-experience) available, and to discuss concern with them before making any kind of report to the Church. The other question arising, given the woeful behaviour of some dioceses or bishops, is to report alleged abuse to an Archbishop (+/- the media). Many victims, witnesses, whistleblowers are silenced. Strength in numbers (as the Bible suggests) can be very important.

Thank you Stephen for yet another blog pointing out Truth to Power.

I just hope Power, especially ++York reads them. If he doesn’t he really is burying his head in the sand and living in a fantasy world (like many other Church of England hierarchy I fear).

I’m not qualified to comment on ecclesiastical procedures (although Just Thinking’s experiences sound pretty criminal, and similar to something I experienced once. Conspiracy to pervert the course of justice comes pretty close.) but one thing occurred to me, and it’s about behavioural culture, both male and church.

I’ve been involved with, particularly, charismatic churches for many years, and am familiar with the ‘huggy – kissy’ culture which they manifest. Indeed, an atheistic works colleague once asked if I attended ‘one of those new-fangled kissing churches’! As a fairly reserved and long playing single male I never felt comfortable with that behaviour – too easily misunderstood, open to abuse and raising too many personal difficulties, physical and emotional for my comfort. In consequence it marked me as ‘different’, possibly ‘not open to the spirit’, or ‘inhibited’. And, like LJMT, finding odd suspicions about my private leanings being held.

At the same time, my work place and most other social circles were moving very firmly back into the old ‘don’t look, certainly don’t touch and mind what you say’ culture – effectively I was becoming more and more aware of the gap between the world and the church, and to be quite honest, felt happier with that of the world.

That ‘huggy – kissy’ culture is too easily exploited and abused. Someone once said it is noticeable that it is the more attractive of the ladies (and men?) that get the hugs from the opposite sex. Couple it with male dominated headship and female submission ideas and it’s wide open for abuse.

Now I know nothing at all about the background to the Liverpool case, save that as usual the authorities don’t seem to have handled it very well. But is it possible that what I’ve just described is a part of the problem? It sounds like the kind of ‘lad-ism’ which we’re probably all too familiar with, totally ignoring the whole concept of respect for other people’s ‘personal space’ which the more sensitive of us have grown used to, and expect?

Another issue with gushing Church emotionalism in public is the stagecraft. Outside of the Church cauldron there can sometimes be precious little real care or intimacy. A smaller Sunday Church (or tiny midweek fellowship) can be more genuinely intimate and supportive. There can be far more mutual sympathy for people’s weaknesses or life gremlins. Lots of people commit to charismatic-evangelical groups and then get bitterly disappointed. There can be shocking abuse of people and/or resources close to the surface, which you start to spot as the months or years go past. There can be a conveyor belt of whistleblowers-witnesses-victims. Wait your turn! Lucky to have escaped a charismatic-evangelical Church where I felt exploited and ill-treated. A contact suggested leaders with property portfolios-yet who preach about poverty-are nauseating in the extreme.

Cottrell vows to stay (Times, p11 3.2.25). What a sick joke we have as-‘acting’-Archbishop of Canterbury!