by Martyn Percy

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/369115/marriages-in-england-and-wales-by-type-of-ceremony/

We, as a nation, have now passed the fifth anniversary of Covid-19. Stay at home. Avoid meeting others. Churches locked. Bishops conducting online services from their kitchens, ritually sanitising their hands (even though nobody was communicated). Dominic Cummings driving to Barnard Castle for some reason or other. Funerals restricted to a handful of mourners. People dying in care homes, with loved ones only able to press their noses against the window in those final hours. The Prime Minister being admitted to hospital and coming close to death. The daily ritual of banging pots and pans for the NHS, arguably the national secular-sacred faith of the realm.

We all have memories of Covid-19 and the two periods of lockdown, punctuated by “eat out to help out”. But as a recent op-ed in The Economist noted,

“Coronavirus in Britain is a story of individual grief and collective amnesia. The fifth-anniversary commemorations on March 9th, which had been designated a “Day of Reflection” by the government, were dignified but modest. In London relatives of the deceased threw carnations into the Thames, as a piper played a lament. Around them, joggers plodded, tourists gawped and drinkers toasted the first pint of the day in glorious spring sunshine. This is a sentimental country, where Armistice commemorations seem to grow bigger each year and new statues are erected to local heroes. But mention the pandemic, the biggest calamity in living memory, and you will be met by a wince and a change of subject. The memory is less of the neighbourliness and Zoom yoga, more of bitterness and boredom…”

A BBC Survey published on 25 March 2025 estimates that as many as 1:10 may have Long-Covid. That’s around 5.5 million in England alone (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c93ker0kevpo). Long-Covid is a new condition which is still being studied. The most common symptoms of Long-Covid include fatigue, difficulty breathing, problems with concentration and memory, aches and pains. Other symptoms include disruption to senses (i.e., such as smell, hearing, taste, etc.), chest pains, difficulty sleeping (insomnia), depression and anxiety, feeling sick, loss of appetite and persistent headaches.

Of course, the CofE does not have an illness like this. Not in reality. Here we are speaking only analogically, and in so doing, I draw on David Tracy and his prescient The Analogical Imagination (1981). Analogically, the CofE is a corporate body with severe malaise, and is experiencing symptoms it cannot make sense of. But what are the underlying causes?

A number of senior clergy have opined that a lot of the struggles the CofE is currently wrestling with have been pinned on to Covid-19. Other senior clergy have expressed scepticism on this, and suspect that Covid-19 has become a distraction for not thinking about the deeper latent problems that were bound to pose issues to the CofE, and eventually become manifest.

I think they are both right. But to understand why the CofE can’t cope with its (corporate, analogical) Long-Covid, one has to look further back.

In their remarkable book Secular Cycles (Princeton UP, 2009) Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov show how societies in Europe evolve and adapt to the bigger underlying cultural, political, demographic templates that shape life, hope, expectations and outcomes. They show, amongst other things, how birth rates, food prices and inflation shape population size. How inflation and stagflation (i.e., the combination of high inflation, stagnant economic growth, and elevated unemployment) impact wages, employment and work. And disease, plague, wars, revolts and natural disasters must also be factored in.

Many historical processes exhibit recurrent patterns of change. Century-long periods of population expansion come before long periods of stagnation and decline; the dynamics of prices mirror population oscillations; and states go through strong expansionist phases followed by periods of state failure, endemic sociopolitical instability, and territorial loss. Turchin and Nefedov explore the dynamics and causal connections between such demographic, economic, and political variables in agrarian societies and offer detailed explanations for these long-term oscillations–what the authors call secular cycles.

Secular Cycles elaborates and expands upon the demographic-structural theory first advanced by Jack Goldstone, which provides an explanation of long-term oscillations. Turchin and Nefedov test that theory’s specific and quantitative predictions by tracing the dynamics of population numbers, prices and real wages, elite numbers and incomes, state finances, and sociopolitical instability. Incorporating theoretical and quantitative history, the book studies societies in Europe during the medieval and early modern periods, and even looks back at the Roman Republic and Empire.

Turchin and Nefedov don’t have much to say about Christianity directly, but it is clear that when one analyses the big social-secular-material cycles, churches are compelled to adapt. As they do so, they incur the consequential symptoms that the larger secular cycles produce. In this regard, Turchin and Nefedov follow earlier work by John R. Moorman, Jack Goldstone and Lawrence Stone

For example, Medieval England had around 10,000 parishes serving three million people. The late medieval parish priest was a semi-literate rural worker. In pre-Tudor England hardly any parish had a resident curate, or even necessarily a parish church. But 1540-1560 saw huge declines in ordinations.

Given the turbulence and violence of the Reformation this is hardly a surprise. In Canterbury diocese in 1560, of 270 livings, 107 had no clergy. In Oxford archdeaconry the numbers of clergy fell – from 371 in 1526 to 270 by 1586.

After 1600 the numbers of clergy in the CofE increased rapidly, and by 1640 there were more clergy than livings (so unemployment). By 1688 there were 10,000 clergy. But the rise and fall in numbers does not tell the whole the story. By the end of the Caroline period, a minister had a university degree, strong religious convictions, a comfortable house, and income on a par with doctors or lawyers, often able to afford domestic help. Ordination was for elites.

This trend continued, albeit in slow decline, during the 19th century, and to some extent the first half of the 20th century. But the post-war years have seen a much, much steeper decline in the public status and professional identity of clergy. Teachers and nurses will be better-paid, and enjoy stronger employment rights.

Today there are 12,500 parishes in the CofE serving a population of 57 million. Under 700,000 attend its services, amounting to just over 1% of the population. With 36% of attendees over the age of 70, the cliff edge looks very steep, with 200,000 set to be lost to the CofE in the next 15 years. They will not be replaced.

With around 50% currently aged between 18 and 69, and only 18% being 17 or younger, the CofE has largely lost its transmission rights. When empires or societies collapse, there is loss or disruption in transmission. What was previously assumed is forgotten. What was once known is no longer learned.

Between 2009 and 2019 the average weekly church attendance for the Church of England fell by approximately 218,000. Church attendance figures fell even more during 2020 and 2021, although this was due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Check the collection plate, in the meantime.

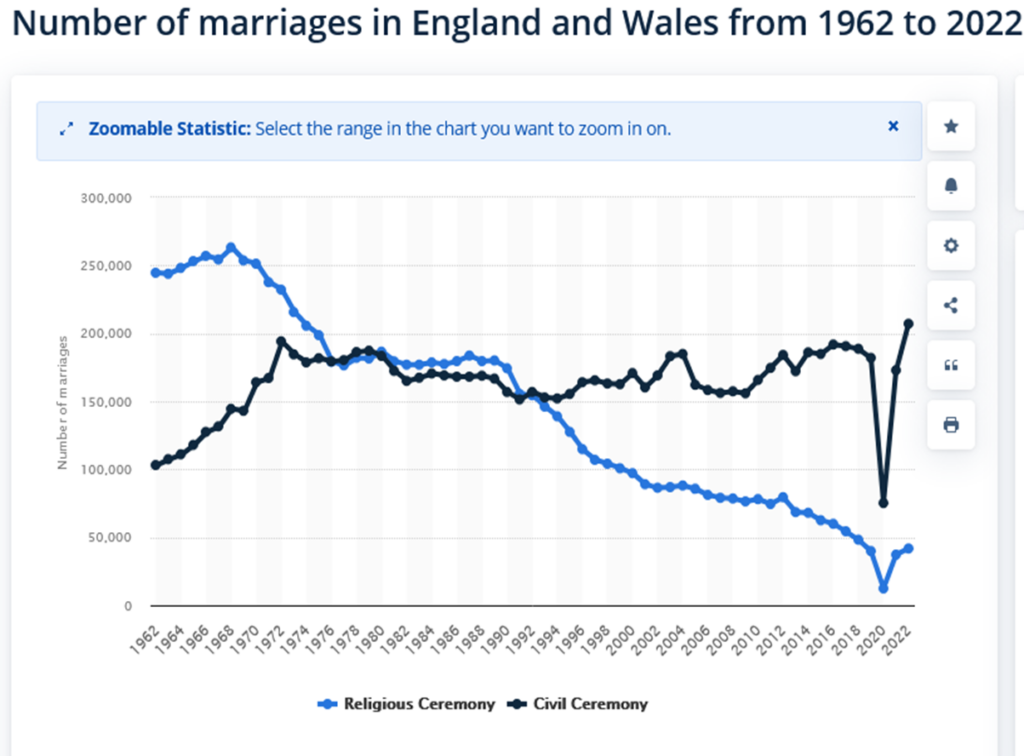

In 2022, approximately 207,004 marriages took place via a civil ceremony in England and Wales, compared with 41,915 religious ceremonies. Since 1992, there have been more civil ceremonies in every year than religious ones. Naturally, there were far fewer ceremonies taking place in 2020 due to Covid. Yet there is no national or diocesan mission strategy, nor even a bishop, getting to grips with any of this. By 2030, the average weekly church attendance for the CofE will have collapsed to around 0.5 million – simply not a sustainable economic position.

That the CofE sits on social and cultural templates it cannot control is hardly news. But there are no national or diocesan mission strategies that show any inklings for engaging with the bigger picture. The CofE thinks it is running out of young people (true). So it pours huge amounts of money, resources and anxiety into reversing this, without ever pausing to consider declining birth rates (there are fewer young people), and that as a population the English are getting older and older, with fewer taxpayers and people at work to pay for the long-term care of the elderly. Young people are extremely anxious about this, and the toll on their mental health and morale is enormous.

The CofE is habitually between 25-50 years behind the times on management, communications, leadership, HR and the like. Initiatives on mission, youth, the elderly, reorganisation, finances, governance, employment and engagement are wincingly out of date, even pre-publication. On safeguarding and sexuality the CofE occupies top spot as a national scandal (and were it not, it would be a national joke). Little of the operational and managerial infrastructure is fit for purpose. The CofE is run by (proverbial) generals fighting the wars and opponents of bygone eras, if not centuries.

On pensions, the recent letter from 700 CofE clergy flagging existential anxiety and poverty has been met with indifference by the hierarchy. As indices of trust are measured across professions, the CofE and its leadership have logged the lowest score on record. People outside the CofE do not believe what bishops say. Inside the CofE, it is hardly any better. Its managers and leaders are out of their depth, yet regard themselves as indispensable, despite being clueless. Locally, for parishes, the annual warmth of seasonal spiritual nostalgia has become a threadbare comfort blanket now so fragile it can barely be touched before being carefully stowed away until the next Christmas or Easter comes.

Meanwhile, theological analysis – which could have been be critical, nourishing and prescient in such a crisis – has been stripped out and marginalised, or ostracised by the CofE’s leadership. Whilst insights from secular social sciences were never really engaged with by the CofE leadership. Corporately, the CofE is like the proverbial frog in boiling water. It has no idea how it got into the kettle, let alone why the water is getting warmer. Alpha Courses, Fresh Expressions, mission statements and another diocesan reorganisation have been, predictably, about as effective as a nosegay in the face of a major plague epidemic.

England was hit hard by Covid as was the CofE. There were 120 days of lockdown in the nation – far more than other countries. Yet our mortality rates were amongst the highest in Europe. It is estimated that the backlog for NHS treatment is still running north of 7 million.

Pupil absence rates in schools remain high, and the bill for the bail-out given to employers and employees (one of the most generous, globally) will sit on the national debt for generations to come. The furlough scheme cost the nation £70bn, which is 2.9% of GDP.

On the ground, locally, rates of stress and anxiety amongst clergy continue to climb, and major issues on morale, mental health, expectations on work, finances (personal and ecclesial), public trust, employment rights and pensions remain unaddressed. Such factors are dogged by other persistent scandals in the church. The nation continues to practice slow-but-ever-increasing social-distancing from the CofE, save for a few festive occasions each year. Nationally, there is no sign of anyone in the CofE leadership grasping these nettles.

As I have recently argued(The Exiled Church: Reckoning with Secular Culture, Canterbury Press), the huge and calamitous adjustments made by the Church of Scotland to its demographic and financial crises could serve as a warning to other denominations on the perils of not thinking ahead. Five years on, Covid has irreversibly transformed the English nation. Which makes it all the more remarkable is that in the CofE, it seems to barely changed or adjusted at all.

So, what about the CofE suffering from a case of corporate Long-Covid? It seems to fit with our collective sense of symptoms. That said, and as Turchin and Nefedov suggest, issues that the English nation (and thus its national church) are wrestling with lie well beyond its control. It remains to be seen if the CofE leadership can read the signs of the times and interpret them, let alone think creatively about the survival and shape of the church over the next few decades.

If there is to be any hope, there must first of all be some realism about the present and future. But the leadership cannot talk their way out the collective crises afflicting the CofE. So we need a lot more show and a lot less tell. We need the leadership to show visible, serious signs of real change that are intelligent, wise and considered. On that, we continue to hold our breath. I fear we’ll be waiting for some time.

Empirically, people who were still going to church regularly, and then weren’t allowed to in COVID, some of them at least discovered that not much happened to them. More time to lounge about on Sunday mornings, or maybe less stress in trying to marshal a whole family in reasonable condition, to get a parking space in time for Morning Service.

Of course a good number missed something really special, a closeness to God or a church community. However many didn’t. It was only a sense of duty keeping them going, and there were many things not particularly pleasant they were happy not to return to.

For me, being at church was part of my identity, a part of who I was. Not being there (and this was a while before Coronavirus) was necessary for my mental health, but left a large hole. I patched this over with psychotherapy and good people around me, and a decade of growth, not all of it painful.

I’m open to the idea of going back to conventional church, but never can quite bring myself to. Besides, I suspect that places like this are a bit of church, often rather better. I still love God, but can’t glibly say what this means.

Each (ex)archiepiscopal blunder just spreads the permission everyone gets not to go back to church. And I can’t really see how the current regime can possibly change itself in the manner suggested, so as to thrive or even to survive.

That’s not to say I haven’t encountered a small number of people here who impress the heck out of me.

Will the Church wake up and listen?

An interesting reflection! BUT-The Alpha Course-does work. And that reinforces just how poor the bureaucracy version of Anglicanism really is.

Pre-pandemic I was a victim of savage evangelical bullying and harassment. There was wanton contempt shown for UK law, church rules or biblical principles of natural justice.

I later shifted from an evangelical parish to a High Church parish, and from Sunday to Wed as a day to receive Holy Communion. The pandemic has caused me to jettison any Sunday or Wed services, bar 2-3 per year (Xmas, Easter or Pentecost).

I now attend a non-conformist centre’s midweek payer meeting. There is more fun-friendship-fellowship there than at any Anglican Church I ever attended. Not in any hurry to go to Anglican Sunday services, and I love/like not giving £1,000 or more yearly to ‘The Bullying Bishop Comfort, Salary and Pension Fund’!

Reap what you sow Anglican Bishops!!!!!!

The best part in Alpha is where they show how many authentic early manuscripts survive, plus the relative amount of references in non-Christian literature in the pre-Fathers or earliest Fathers period. These subjects deserve far greater publicity altogether, and without being solely associated with one “brandname”.

Many thanks for this very intriguing piece. I’m a bit over 7,000 services in as many churches during the course of my continuing pilgrimage and, save in comparatively few bright spots, this article rather reflects the trajectory of the Church as I have experienced it in every diocese. A sort of creeping and cumulative inanition. The whole institution is so suffocated by its own Rococo structures and self-serving vested interests, and often so attenuated locally, that I have long concluded that it is incapable of meaningful reform and that what matters now is preventing the privatisation of the buildings so that at least something can be salvaged from the wreckage for public benefit (in contrast to Scotland). The pandemic almost certainly accelerated existing trends, most especially the effective loss of witness and worship in many communities, and in some urban environments, as well as in significant tracts of countryside, the Church has more or less expired completely; I cannot help think that many of those in authority regard such outcomes with impassive indifference, regardless of feeble protestations to the contrary.

I would be interested to know Dr Percy’s views about the Radical Action Plan in Scotland, not least because schemes implemented by certain dioceses – the Lincoln ‘Time to Change Together’ programme, or the Ely 2025 programme, appear to have been ‘inspired’ by it.

It would also be useful to know the sources for the remarks made about the early modern dioceses of Canterbury and Oxford (Christopher Hill?). Did the price revolution of the sixteenth century retard or accelerate improved pastoral provision? Was the absence of adequate provision prior to that transformation due to the long shadow of plague, of the resultant falling returns to rents and of corrupt practices, such as ‘church chopping’ or of the way in which in many parishes (where government ministers were patrons) parochial revenues were used to pay priests in state employment?

Many thanks again.

In haste, Froghole. My sources on Canterbury, Oxford, etc come from Turchin’s book, Christopher Hill, etc. The 17th century revolution seems to have had little financial impact on the parish clergy, though, of course, during the Cromwellian Commonwealth, Bishops were the poorer for the changes. The plague might (oddly) have benefitted the church through legacies, fees etc.

The Church of Scotland Scheme, currently underway – 40% cut in buildings etc – has been centrally organised and implemented, with predictable results. Communities that have been told to close their churches have begun buying them off the CoS, and now that they own them, they get on and hire their own ministers (in the Reformed Tradition, but not necessarily CoS). I was present at a CoS parish church the other week, and the vestry is just getting on with making sure they have a 0.5fte minister that they will employ and house, but that minister will not necessarily be CoS.

In the Presbyterian system, local autonomy is assumed, so these kinds of initiatives don’t have the ecclesiological consequences that might pertain to the CofE. But we don’t have to travel too far back in time to the era of Jane Austen to find CofE parishes looked after by local benefactors and patrons, and with minimal episcopal oversight.

My sense of Lincoln’s ‘Time to Change’ is that it is neither flesh nor fowl. The CoS, in its retreat from centralised bureaucratic oversight of every parish in Scotland, has now meant that the parishes can make their own pastoral arrangements in future, and effectively the locals take control. Similar things have been done in rural Australian Anglican dioceses – the diocese says it will close the church, the community buys it, and then makes its own arrangement to hire a local (ecumenical, retired, etc?) clergyperson. This is happening.

I suspect that CofE dioceses/bishops will be reluctant to cede control in this way. Equally, they cannot afford the pastoral provision locals want. Something has to give. The current situation, where the centralised bureaucracy demands more money for less provision, and expects to drain more power/autonomy from local communities/parishes and presumes to make decisions on what locals can have, is a recipe for increasing resentment and eventual revolt. I think the entire funding model is broken, and can’t be fixed from the inside. A Royal Commission would be a step forward in determining what is to be done. I am certain that no diocesan strategy has, or will, grasp these nettles.

An interesting perspective, as always, Martyn. I just need to point out to Froghole that Ely 2025 is a plan created in the first half of the last decade, and so is not in any way inspired by the Church of Scotland. Frankly, I doubt that the more recent Lincoln plan (under the same Diocesan Bishop) is, whatever similarities there may be.

Thank you very much indeed for this response (and also to Paul H.). On periodic visits to Scotland I have been staggered and acutely distressed by what has been happening.

My understanding of the regime in Scotland is that the General Trustees gained title to the property after the passage of the Church of Scotland (Property and Endowments) Act 1925. The ‘quoad omnia’ church buildings were hitherto the property of the heritors (i.e., parish landowners) who were liable for upkeep, except in the burghs where the councils had the liability. Prior to the transfer of title the heritors/burghs were obliged to put the buildings into repair. Thereafter, the liability for repair fell to the congregations.

As such, and as in Ireland and Wales, there was an asymmetric and imperfect realisation of economies of scale. The congregations had all of the disadvantages of centralisation in the General Trustees, without any of the corresponding advantages. As attendance has undergone a remorseless decline, the pressure on the presbyteries and congregations has only increased. Moreover, since the Kirk was much more comprehensively disendowed after c. 1560, there was no substantial central fund based upon the expropriation of episcopal and capitular assets, as in England after 1840.

What I had been told (but I cannot be certain that it is true) is that after the attenuation of Heritage Lottery support in 2016-17 the Kirk appealed to the devolved administration in order to make up the difference and were rebuffed. Therefore, the General Trustees panicked and forced the RAP through a frightened General Assembly in 2019. I suspect that the General Trustees were thoroughly alarmed well before 2017. In any event, the object is to turn the Kirk from a denomination exercising a ‘territorial ministry’ (as per the Declaratory Articles in the schedule to the Church of Scotland Act 1921) into a ‘gathered’ denomination in which provision is effected in what are perceived to be the ‘right places’. Why that should necessitate the closure of certain major burgh churches (such as the High Kirk in Inverness) has not been adequately explained, but it is evident that drastic closures are being effected in rural areas (i.e., practically everything in counties like Berwickshire or Selkirkshire), as well as in affluent suburbs or exurbs. When even churches like Whittinghame (viz. the Balfours) or Braemar (on the Balmoral estate) have been shuttered, then it is clear that nowhere is immune. The RAP will almost certainly be an abject failure, with much of the stock being sold off for a mess of pottage.

My understanding of Time to Change Together is that it was devised by Nigel Peyton (formerly bishop of Brechin, and now an assistant bishop in Lincoln) with Alyson Buxton (archdeacon of Stow & Lindsey). Peyton and Buxton were, as I understand, tasked with preparing a scheme which would resolve the DBF’s £4m deficit, which the Commissioners were unwilling to assist with. The DBF, despite having a glebe endowment of c. £100m, was unwilling to see it eroded further. I was told that Peyton took stock of the RAP, and noted that a variant could be applied to Lincoln (which, pace Paul H., may or may not be true). Thus, there is much the same pseudo-self-grading system (PCCs grading themselves from 1 – full provision – to 5 – closure). The upshot is that there are a handful of grade 1 units, about 30 grade 5 units, and about 180 grade 4 units where worship is often extremely attenuated. Areas already affected by heavy closures such as South Lindsey (i.e., mostly East Lindsey District Council) are being hit the hardest. However, even before TTCT was completed, the deficit had been more than halved.

My view is that dealing with the buildings is essential to breaking the jam, but I suspect that I have bored readers here and on TA with my ideas about that quite enough already. Very many thanks again for this (and for your ‘Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism’, which I much enjoyed)!

Glad you enjoyed ‘Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism’.

You are spot on with the fiscal history of the CoS. Currently, the closures are inspiring shock and dismay, and churches such as the High Kirk in Inverness just one of many examples of closure that cannot fail to send a signal to the wider population – that the CoS is in retreat, declining and effectively pulling out of territorial provision. Here in Aberdeen, Scotland’s third city, the High Kirk of St. Nicholas has been closed and sold. It has an 800+ year history. This leaves the city centre with no CoS presence, and Presbyterian presence fighting a rearguard action in the suburbs.

It is hard to envisage how some CofE dioceses, perhaps many, will avoid the same end as the CoS, though the manner of journey to get that point will be longer, more convoluted and complex. As there are wings of the CofE that are strongly in favour of intensive /gathered congregations rather than territorial/extensive ministries, this further complicates the drivers for decline. But essentially we are dealing with the CofE unwittingly engaged in self-secularisation and unable to figure out the alternatives.

Perhaps an obvious thing for the CofE to do is audit the strategies that dioceses have developed and implemented over the last five decades. Have any worked? What were the results? How were they implemented? What lessons could be learned from these initiatives? I think we would be in ‘pottage territory’ here, for sure. But such an audit exercise might prompt the CofE to reflect on whether it is able to resolve the issues that have led other denominations being overtaken by accelerating decline.

Very many thanks for that, and I note that even erstwhile cathedral status will not protect a church from closure by the General Trustees, as with Brechin Cathedral in 2021 (this is not unlike Ardfert Cathedral having its roof removed in 1871, or Elphin Cathedral being demolished in 1964).

In my view there is a solution (though one inimical to proponents of gathered worship), which is to acknowledge that the Commissioners have had a free ride on parish share since 1995-98. That free ride may amount to about half of the present £10.4bn fund. Therefore take £5-6bn from the Commissioners and vest it in a national religious buildings agency (plus contributions from other denominations who may wish to participate). The buildings, or most of them (especially those funded by past taxation) are vested in the agency. The agency, using the dowry, generates economies of scale which PCCs will never realise, and it will have the bargaining power to negotiate discounts with contractors that PCCs will never achieve (or it could have its own contractors). In exchange the Church gets a perpetual free right of use to the vested stock, and so preserves its reach. PCCs and incumbents are liberated from the burden of the buildings, and so can concentrate on mission and outreach.

In exchange for the partial disendowment, the Commissioners are compensated by means of a transfer of diocesan assets (mostly glebe appropriated in 1976), and the diocesan administrations are folded into the Commissioners and rationalised. The Commissioners then generate economies of scale in the management of the Church which 42 diocesan administrations will never realise. The dioceses would continue as pastoral agencies, and bishops would be liberated from much of the burden of administration. In addition, certain partisan parishes would be less able to exert ‘suasion’ over the bench via threats of withholding parish share.

The analogy is with the NHS – for all its faults having a national risk pool (in which everyone cross-insures everyone else) reduces the overall premium as much as possible. Collective insurance is always and everywhere cheaper than self-insurance (compare the cost of health care with that of social care, where self-insurance prevails). However, in the ‘national’ churches of the British isles PCCs and congregations have to self-insure for upkeep, resulting in a large and unnecessary bleed of capital, as well as compromising the future of Christian witness and worship in many communities.

Of course, a reform like this will never happen given the present nature of the Church of England as a confederation of warring interest groups. Most especially such a reform would never occur because it would seriously compromise the ability of such interest groups to yield power within this ramshackle confederation (which, in my view, is exactly why such a reform should be implemented).

Very many thanks again!

Froghole, this is precisely the kind of solution that is needed, but equally one that the CofE won’t be able to sponsor. A Royal Commission could take hold of the issues and use parliament to impose a solution that would effectively give the CofE a lifeline. Alas, the internal CofE factions are too busy fighting about gender, sexuality, liturgy, etc to notice that there will be no platform to fight on unless the leadership gets a grip.

Many thanks, Prof. Percy! I do agree I drafted an outline bill along these lines nearly a decade ago, as I had concluded that the state would have to cut the Gordian knot. It was intended to be fairly conservative and protective of the Church’s interests, in a [vain] effort to appeal to the authorities.

The outline bill was based on an amalgam of the 1869, 1905 and 1914 disestablishment and disendowment statues for Ireland, France and Wales, but also the 1921 and 1925 statues for Scotland, plus the National Heritage Act 1983 (that last statue was used to develop a constitution for the agency in which the stock could be vested).

I would have to re-draft it as it was saved on a now-defunct account of mine, but Simon Sarmiento at TA might still have a copy, and I think another was sent to Jonathan Chaplin.

The missing component was a draft Measure which would wind up all of the diocesan bureaucracies and transfer most of their functions, and all of their assets, to the Commissioners. The draft bill was sent to the then Third Commissioner, who indicated that it would be passed to the Legal Office. Having disappeared into the maw of the ecclesiastical bureaucracy, it was never heard from again (and was presumably consigned to the circular file underneath the proverbial desk). After a while, I concluded that it was probably futile taking it any further, but I sometimes mention it when I am told that some closure scheme is necessary on a TINA basis, simply to remind people on my travels that there are possible alternatives and they shouldn’t necessarily take what the diocesan authorities say to them at face value. Many thanks again!

We are auditing our diocesan strategies here in Norwich prior to developing a new one. In answer to the questions about which diocesan strategies have most helped your parish etc. , many (most?) are saying none have.

We are taking the view that we must face some hard truths before formulating a new strategy. The new strategy will ‘renew and resource the parish for mission’ (let the reader understand). I cannot, I think, say more until more of the work is in the public domain.

In Dr Percy’s article some reference to “bishops” presumably indicates a monolith they too often find themselves lumped into by their bosses the bureaucrats, against the wish of the better ones (some female and male ones).

If the C of E hadn’t swallowed John Stott’s doctrinal starvation rations whole (note Jesus’ parables of rations, Old Testament warnings re. rations) surely its more alert leaders could have warded off the imposing of the mysteriously named “Archbishops’ Council” in the 1990s (which is nowhere enjoined on us in Holy Scriptures).

Martyn Lloyd-Jones hadn’t said how long he was “giving” them but they had, overnight, spurned the wisdom of ordinary nonconformism (which wasn’t attempting to usurp what till then had been genuine C of E organising flair) only to run straight into the arms of the fashionably manipulative Wimber and Falwell Senior.

Thus some of them also missed a 1990s trick re. welcoming women clergy, and almost all missed a trick in helping parishioners (according to whatever taste) round the Kansas City “Prophets” and related phenomena. Whatever the earlier originator of Alpha (and I’ve done most of it twice) had in mind, this apparently metastatised into a realm of (pretend non) Torontulated Bromptosauruses.

C of E leaders shouldn’t go about everything in either such a “pretend classless” sort of way – very Cleeseian – or the high handed neo-imperial anti-intellectuality of most of their mentors’ mentors and controllers. Genuine learning about meanings is not something to be ashamed of sharing out among our peers.

Stott’s not seeing Holy Spirit in us (which according to Hermann Cohen in Religion of Reason, was the aspiration of the Old Testament writers and their most thoughtful followers) shows up how poisonous his attempt really is, in declaring irrelevant “most of” pneumatology and all of eschatology (the very reason Jesus ascended to impart One Comforter so that they could intercede: and the New Testament clearly contains both one-stage and two-stage initiation).

“Don’t forsake meeting” means with fellow synagogue members – they had the Last Supper in common – which sadly (contingently) faded after about 130 AD. Not honouring the gifts in you and me (I Cor) resulted in some falling sick (sick ideas) and some of them falling asleep (dead hands, dead beat, dead wood, dead in the water, dead on their feet) (this is my opinion anyway).

In my periodic brushes with it, “New reformed” religion is neodarwinian, instrumentalist, hegelian, material-monist-deterministic, we (including vicars I’ve known) just puzzled figments (and that’s before we ever want to put in any complaint). Whilst in Jeremiah and Ezekiel as Cohen points out, affect (what in an Authorised Bible I remember was rendered “bowels of mercies”) is what motivates to the ethics of the actual Bible doctrine.

As for equable sharing of finances and looking after precious real estate, there is no resort but to get prayer caps on. I repeat lots of Glory Be’s because situations defy articulacy (“groanings”). Armed with these ideas I’m planning to go back to my last C of E church, which I had fled, 8 months before it “officially” exploded. I believe in all the spiritual gifts, far more than the movements and their bewildered denizens do.

Likewise, there was a wealth of detailed information re. covid, months before miscellanoeus misreactions by officialdom – who are genuinely busy and need God’s good angels sending to help them. If it doesn’t cross the minds of our prominent spiritual lords to pray II Chr 7:14 and Daniel 9: 3-21, we shouldn’t await their permission (priesthood of believers).

The ‘elephant in the room’ is surely how a man like John Smyth QC got protected for so long. What does that really say about Anglican Church culture?

Anglican leaders have tried a ‘get out of jail card’ along these lines: there was a lot of abuse historically of various forms, but we have invested in new diocesan systems so that the problem is now sorted, and the mistakes of yesteryear can never again be repeated.

John Smyth QC may indeed have been something of a freak of nature, both in terms of the scale of harm he did, and also his ability to hide it. Yet we see countless other evangelical abusers now coming to light. Also, what happens if one talks to lots of relatively recent New Wine or Anglican trainees? Are there plenty of escapers, victims of bullying and harassment, who just leave the Anglican scene or minimise future commitment?

Everyday exploitation, bullying or harassment, or a combination of these with some victims, may be one of the greatest threats to the health of Anglicanism. In an age when secularism is so dominant, it takes courage to go forward for ministry training. Family, friends and colleagues can all be surprised, and also fascinated, by someone doing a ministry traineeship.

Lots will honestly ask: “Are you wise, in an age of utter scepticism, devoting time and money and emotional energy to this stuff?” It is profoundly embarrassing, after getting evicted from Church ministry opportunities on spurious grounds, to face these friends-family-colleagues. What do you say? “I was viciously bullied, harassed, exploited and the local Bishop laughed at it all. I should have listened to your wise advice”.

The worst part of the Smyth case is that he exploited a moral vacuum. That moral vacuum has facilitated kangaroo court justice on an epic scale, and lots of ex-Anglicans or fringe-Anglicans, including some formerly very committed to the denomination, have just had enough of it.

I wasted years doing theology qualifications or programmes, spent thousands of pounds in the process, and was then viciously bullied and harassed. The Anglican Church sought to quietly cover it all up. A senior non-conformist minister advised me to leave the local diocese, to escape unlawful harassment and savage bullying.

This type of bullying might appear to be endemic. Empty parishes and clerical vacancies are consequences of bullying on a horrific scale. Abused and bullied children capture headlines when problems are finally exposed. Bullied adults simply leave. Our Bishops’ blasphemous contempt for biblical principles of justice reaps a reward, and this is plain to see if one studies UK Anglicanism.

Its dominance of evangelicals in the problematic category is largely a function of demographics.

Every other tendency and none have had their share of issues.

The Raj oppressed religions other than its big two and misused theism concepts. Now reimporting its false dialectic to England, it induces each group to let their emotional attachments clash with everybody else’s emotional attachments:

– varieties of same-sex blessing concepts

– varieties of concepts of “ordinance”

– church “growth, planting or seeding” concepts

– attempts by “loyalists” and “dissidents” to distort other denominations

– publicity concepts

– ideal organisational concepts vainly hitched to safeguarding and redress needs

– financial concepts

– “distinguished public service”

Jesus would say: overtly proclaim your moral autonomy at every level (how about placing intercession and supplication top), then healthily mourn the unattainability of much of the rest.

Ivan Illich, a RC priest, deplored the growth of bureaucracy in religion and the exporting of advanced notions to supplant existing and already better belief systems. Is a dominant faction’s seeking to dominate by prompting emulation at home, a mirror of this? Have the Brompton Two (rightly pointing out weird procedures recently) realised that making the Archbishops’ Council veto Synod from inside, wasn’t such a good idea after all?

Before Stott, apparently, was Nash copying an overdeveloped sense of duty from Torrey (a Moody Institute marketing machine clone), furthermore Nash reportedly didn’t mix enough, looked down on intellect – and how many heads of Min of Education did he train up let alone churchmen?

Not teaching those around him critical thinking on post-Manifest Destiny dispensationism: do those who got burned fingers and cold feet from Woolwich Bishop John Robinson’s common denominator, now think that deferring fullness of current christian life sine die and hobbling along with half a Holy Spirit (including friends of the pretend charismatics) are sufficient?

A commenter on a Thinking Anglicans thread in recent months asked whether there is a “larger” story behind the recent miscellany of problems? A mishmash of patchy doctrines – especially the “new reformed” illusion that Sovereign Jesus is gliding us nicely towards some bourgeois “omega point” – are parts of that answer.

Recently we went to see Peter Kay at the O2. These vast arenas are the modern equivalent of cathedrals of worship.

People pay (good money) to be emotional for a couple of hours. In this case the predominant emotion was laughter, even joy. The humour can be edgy, often with a streak of anger behind it , mocking the micro-injustices of everyday life, or the trends we are expected to comply with. Most people got it.

It wasn’t just stand up, there was a great deal of theatre, with PK being transported high above the packed stadium, with smoke and streamers. Something for all the family. A rock star appeared to shrieks of delight. My wife told me afterwards that this had been a hologram. She’s more technical than me.

Church can be like this. Even in the U.K. Whether or not in an actual church building, or hired theatre or school, people pay to be moved. In our town we have many congregations to suit different tastes, as well as declining Anglican congregations. If you don’t get the mix right, contributions dry up, and the church closes.

HTB has been particularly good at running congregations that haven’t closed, whether in implanted churches or seeded in non Anglican congregations (no parish share required).

At the O2, we aggregated with thousands of others. Aggregation is a facsimile of community, but not real church. Earl Hopper describes this (2003) as a way of being together without relating purposefully with the underlying task being served. There’s an incohesion perfectly illustrated in the crowded tube on the way back, where there’s no talking to people we actually probably have a lot in common with, and are sat next to, but never see again.

We are not doing church as Christ specified for us.

While I certainl agree both that one format of church does not suit everyone, and that our services need to engage with people, what – in practical terms – are you suggesting? Most churches have very limited resources in terms of both finance and personnel, they may be constrained by operating in an ancient building, yet they have to put on a new “show” every week.

COVID taught us we don’t need (so many) buildings. Jesus didn’t seem to use buildings very much at all, although these can be hired for specific purposes, like the upper room, although this may have been pro bono.

How did He lead 12,000 people up a mountain? Marketing was word of mouth, and he specifically met them at their point of need: physical/mental/spiritual healing. Actual food for all those people. I’m suggesting food banks may be part of what we might “do” today. Healing: we may have to rethink what we offer here after all the fakery of recent times.

If we set up a weekly entertainment show, and that’s ok as far as it goes, we will get people expecting to be entertained. And we will find ourselves in competition with others, without structural legacy overheads and heritage architecture to maintain.

Paul didn’t take a salary, but worked in the textile industry for income.

Our Lord made a beeline for people who couldn’t profit him, and He avoided or was overtly disrespectful to the established religious regime.

Whatever church looks like, it doesn’t look much like what we’ve been doing on a Sunday

Sunday can easily become very lacklustre in any tradition. I once came across-“a faithful attender and a good payer”-who sought extramarital encounters before and after their traditional 90 mins Sunday non-conformist service. Right clothes, smile at the door and appropriate handshakes fitted the bill, and they were a communicant member in good standing. After this person’s funeral, the parish team discovered things were very far from what they seemed to ‘the institutional church family’. The real story only came out by a few flukes. A participatory midweek prayer meeting, in a smaller group, can be much more authentic and alive, with living people getting to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses……..

Piecing together my observations and reading matter, “evangelicals” within the C of E, an explicitly hegemonist tendency within (then) an only potentially hegemonic one, had dominance all along despite their sob stories. Only when John Robinson took the same watered-down syncretism as John Stott’s, a little further, did they become agressive towards believing middle of the roaders not of their overt style, tempting the latter (and any political bystanders) to repay in kind since.

15 years seemed a long time while it was happening, but Stott turned up his nose at the “sectarian” spiritual wisdom of Lloyd-Jones for the “emergent” material manoeuvring of Falwell Senior and Wimber. We were used to the image of faddist vicars from TV entertainments, whose directors must have known whom they were lampooning.

Now we have the St Helen’s element consecrating sacramental ministers, just when they should be getting away from sacraments (other than baptism) altogether, which not only don’t have meaning in “evangelicalism” but may not work widely in an era of “blessings”.

Outside any anglocatholics who are being left in peace, and the average traditional “dawn communion”, “communion” should definitely not be hyped, for the foreseeable. That and better attention to detail in relationships and practicalities is needed. And to stop hoping to swing headquarters milieux while those have been somehow hamstrung (self-announced moral standards should prevail over conflicting organisational ones).

At a midweek communion in a room with chairs in a circle, it was impossible to evade both communion and the strange “blessing” as I was simply there in order to go to church (but on Sundays one can stay out of the queue).