by Stephen Parsons

This blog post is written at a time when we are witnessing some deeply destructive divisions in the Church. In surveying some of these dividing issues, I am certainly not the first person to notice how many of the contemporary points of profound conflict among Christians have links to issues of human psychology. The classic theological conflicts of the past – the filioque debate or the question of whether the second person of the Trinity is of ‘like substance’ to the Father or of the ‘same substance’ as the Father – were of a different order. The winning side in this latter debate was the ‘same substance’ cohort. Their victory is written into the so-called Nicene Creed, an elaborated version of which we still use today after 1800 years. Another debate which caused bloodshed and acrimony at the time, the Filioque controversy, has settled into an uneasy truce, with the Western Church adopting it and the Eastern Churches with the Anglicans of Scotland opting to leave out the word from their versions of the Creed. In summary, Christians are still divided but the things which separate them now are quite different.

What are the issues that currently divide Christians, even those that belong to the same historical groupings/denominations? If we dig into church history, we encounter many debates and divisions, such as those dividing Arminians from Calvinists. Today we find, in some circles, lively debates centring on the attempt to create a normative statement to explain how Jesus’ death on the Cross allows his followers to obtain salvation. Such theological debates are still important, but the topics that today are really causing the greatest passion, as well as division among Christians, seem to have less connection with purely theological matters. My contention here is to claim that by making some church issues, like the ministry of women, of ‘first order’ status, they are given a centrality which does not belong to them. To argue for or against the ministry of women in terms of priesthood, ministry and leadership is surely not a key matter affecting our ultimate eternal destiny. No Christian should wish to place another Christian who had another view on women’s ministry into ‘Room 101’. And yet the contemporary debates about women (and the LGBT divisions) seem to inherit some of the passion of the mobs that plagued the streets of Constantinople in the 6th century, killing rivals from another theological position. Will the Church ever be able to flourish when we anathematise each other with such passion over these second order issues?

Perhaps I should summarise my observations about the discussions on the role of women in the Church in this way. Those who debate in this arena on both sides seem to derive much, if not most of their energy to sustain their position from their personal psychology. In other words, we are normally witnessing more in the way of passion than a rehearsing of the traditional theological debating points. Over the years, I have listened to the arguments from Scripture about the need for women to accept subservience in church matters and keep silent in church. Then there are the other stock arguments from the Orthodox and Roman traditions about the witness of 2000 years of male priesthood, as well as the evident maleness of Jesus’ original band of apostles. All these arguments have been rehearsed countless times. As far as the Anglican Communion is concerned, an unsatisfactory truce has been declared, and two integrities, representing both sides of the debate are allowed a place at the table of normative Anglicanism.

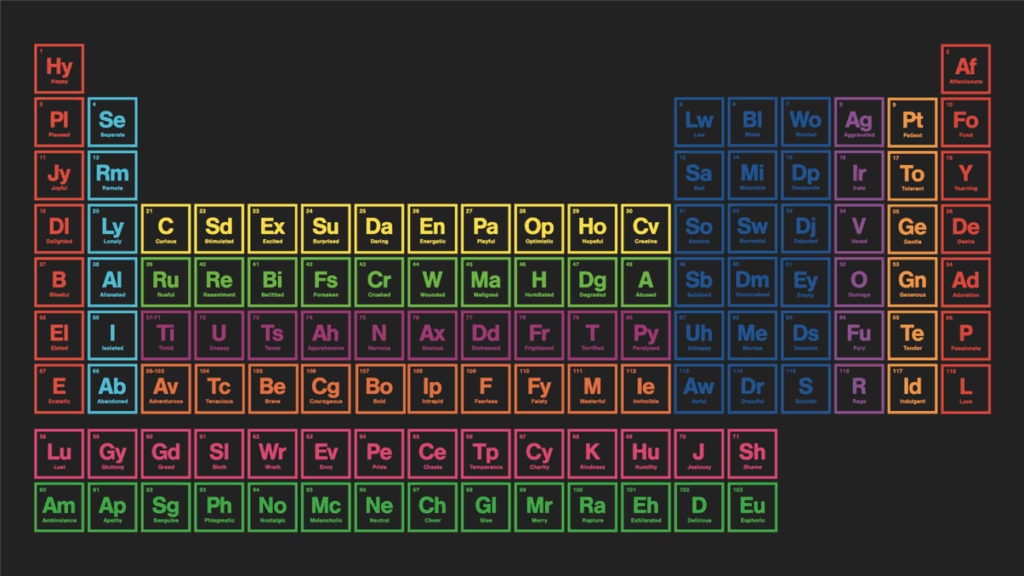

My position in this debate is to side strongly with the cause of women’s ministry. I nevertheless regret the fact that we have these deep damaging divisions fed, I believe, by the passions of human psychology rather than reason and theological debate. I do not propose to raise further issues that surround the LGBT debate. I merely observe that it is hard to even think about, for example, homophobia in the Church and not recognise that personal psychological issues on both sides are embedded in this debate. Many of the issues which are brought up in discussing the place of women in Church draw on similar human passions connected with human identity. Each side in such a debate will draw much from the individual’s personal psychological story while trying to wrap it up in the calm rational language of theological discourse.

As a supporter of the cause for women in ministry at every level, I draw attention to the way that there have been many parallel attempts to downgrade the role and status of women in the secular world. As a school leaver who worked for a short while as a hospital porter, I found that the women I was working alongside were being paid substantially less for the same job. The unfair treatment of women, then and now, could be summarised as an institutional misogyny. Misogyny is a word which covers a range of attitudes towards women, some involving strong emotions of hatred for the female sex. The word is also used to indicate a low-level irrational dislike by men for the opposite sex. Misogyny and its associated feelings creeps into the arguments and divisions about the place of women’s ministry in the Church. Whether we are aware of it or not, misogyny is never far away from the discussions about the role of women in church and society. Because misogyny is a feeling it draws its energy from irrational roots, making it a poor guide to justice and clear reasoning. Emotional energy will always be a part of any debate but a reliance on such primal energy is dangerous for the cause of truth. We need to admit that such feelings can act as a distorting lens for any issue under debate. Identifying misogyny (and homophobia) should alert us to the probable emergence of passion and primal feeling. These so quickly distort and destroy calm and rational process. Arguing from a position of passion and feeling makes it likely that we have gone beyond a position of compromise or reconciliation. The supporters of feminism and female leadership draw on their own resources of passionate argumentation. It sometimes seems that neither side in the debate has any incentive to give way to the other, and so we are not likely to see the argument ever resolved this side of the Second Coming.

What are the classic reasons given to explain the appearance of misogyny in contemporary society, one which feeds and encourages the stance, one seeks to deny women an honoured and full place in church ministry? It will not be a surprise to see that I neither have the space nor the expertise to answer such a mammoth question. But amid all the material on the topic, there is one fascinating observation from the psychology literature which throws unexpected light on the male-female struggle. I am not sure of the origin of the psychologically based observation that I am attempting here to summarise. Books on feminism and Christianity mostly disappeared in my great book purge of recent weeks. The argument that I want to rehearse here, which I found very compelling when I read it, starts with the insight that many men feel a strong need to control the women in their lives. They find it difficult to accept them as equals or, worse still, stronger in some important respects. Women seem to have access to dimensions of emotional power which most men do not have, and many men are afraid of it and jealous of that power.

The fact that the male sex is biologically able to exert physical power over the female sex is an important given in the ‘battle of the sexes’ being played out in our contemporary culture. This potential for physical dominance is acted out in many domestic situations, and it is suggested as many as 25% male/female relationships see violence as being part of the relationship. One factor that is often overlooked and may provide a key to understanding why men feel a need to physically dominate their female partners so commonly, comes from a universal male vulnerability. Every boy was once a small defenceless creature, utterly dependent on a woman for food, safety and the physical touch needed for survival. In other words, every male child was once totally dominated and dependent on a female. Men can never escape that memory of physical enmeshment with their mother. For many men, determined to fulfil the male role of being the one in control and a powerful creature able to dominate and exercise power over others, this is an intolerable memory. Might we suggest that violence and the mistreatment of women is a kind ‘revenge’ against the female embedded in one’s memory and who was once in total control. This insight makes a lot of sense as it seems to explain that strange combination of fear, worship and resentment towards women that exists in many men as they fail to produce rational patterns of thought and attitude when debating the role of women in the church. For that debate to take place properly there needs to be a far better capacity for the sexes to engage with these psychological primal issues. I fear that many men, even in the Church, will be unwilling to make this journey to face their vulnerability in this way.