by Robert Thompson

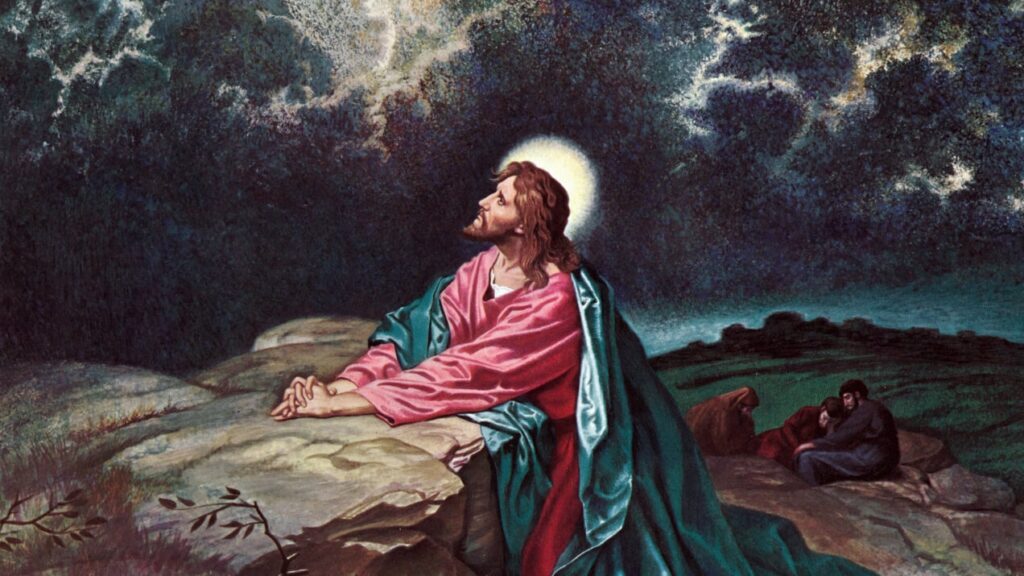

Remain here with me. Watch and pray. Matthew 26:38

Safeguarding failures in the Church of England are often discussed in procedural terms: governance, independence, lines of accountability, and the adequacy of review processes. These questions matter, and they deserve serious attention. But they do not, on their own, explain why safeguarding crises continue to recur, even after repeated assurances that “lessons have been learned.”

What is increasingly clear is that the problem is not only structural. It is theological.

The theologian Marika Rose has argued that Christian theology is marked by a persistent desire for innocence: a wish to present the Church as fundamentally good, morally coherent, and well-intentioned, even when confronted with evidence of harm. In her work A Theology of Failure: Žižek Against Christian Innocence, Rose suggests that theology repeatedly seeks to protect itself from failure, rather than allowing failure to speak truthfully.

This insight has particular resonance for Anglican safeguarding culture.

The Church of England often responds to safeguarding breakdowns by emphasising process: the independence of reviews, the robustness of structures, the good faith of those involved. These claims are not necessarily false. But they function theologically. They reassure the institution that, whatever has gone wrong, its moral core remains intact.

For survivors, this reassurance often lands very differently.

The insistence on institutional good intentions can feel like a refusal to remain with the depth of harm that has occurred. Anger and grief are treated as threats to stability. Calls for accountability are experienced as challenges to ecclesial unity. The result is a culture in which safeguarding is endlessly reformed but rarely re-imagined.

Rose’s theology helps name what is happening here. Failure is treated as an interruption to the Church’s life, something to be resolved so that normal service can resume. But a theology of failure insists that breakdown is not merely accidental. It reveals something true about how power, authority, and self-understanding operate within Christian institutions.

This matters because Anglican ecclesiology is often tempted to resolve safeguarding tension by appeal to balance: pastoral care on the one hand, institutional continuity on the other; accountability tempered by grace; truth held alongside unity. These instincts are deeply Anglican, and often admirable. But they can also function as mechanisms of avoidance, softening the force of failure before it has been properly faced.

The cross challenges this instinct. At the heart of Christian faith is not balance, but exposure. Authority collapses. Innocence is stripped away. Religious power is revealed as capable of grave harm. Any safeguarding theology that rushes too quickly to reconciliation or restoration risks bypassing the truth that the cross discloses.

This is where Anglican debates about safeguarding independence often falter. Independence is treated as a technical solution, rather than as a moral and theological demand. Reviews are expected to restore trust, rather than to tell the truth, whatever the cost. When independence becomes a means of institutional reassurance rather than institutional vulnerability, it reproduces the very dynamics it claims to address.

A theology of failure suggests a different posture. It does not deny the importance of structure, policy, or leadership. But it insists that the Church must relinquish the desire to appear innocent. It must accept that some failures permanently wound the institution, and that trust cannot be managed back into existence.

For bishops and senior leaders, this is an uncomfortable position. They are tasked with holding the Church together, maintaining public witness, and preventing collapse. But when stability is prioritised over truth, the Church risks repeating the conditions under which harm occurred.

Safeguarding reform that is not accompanied by theological honesty will remain fragile. Procedures may improve. Language may change. But survivors will continue to sense when the institution is more concerned with its own coherence than with their reality.

The Church of England does not need to become flawless in order to safeguard well. It needs to become truthful. That truthfulness will not always look like success. It may look like loss of confidence, loss of authority, and loss of control.

A theology of failure does not offer a programme for renewal. It offers a discipline of staying with what has gone wrong, without rushing to redeem the institution’s image. In the long run, that discipline may be the only ground on which genuine safeguarding culture can grow.

The gospel already gives us a language for this moment. In Gethsemane, Jesus does not ask his disciples to act, resolve, or redeem. He asks them to remain: “Stay here with me. Watch and pray.” Their failure is not cruelty but flight — an inability to remain present to fear, grief, and impending loss.

Safeguarding cultures fail in much the same way. The rush to process, closure, and reassurance often masks a deeper refusal to stay awake to what has been revealed. A theology of failure is, at heart, a Gethsemane theology: a discipline of presence that resists sleep, refuses innocence, and remains with truth long enough for something other than self-protection to emerge.

Until the Church learns to remain with failure without rushing to redeem itself, safeguarding reform will remain fragile and the gospel’s judgement will remain quietly in place: then he came and found them sleeping (Matthew 26:40).

It’s good to see Robert Thompson writing on these pages. Whenever I read something he writes I usually learn something valuable. Today is no exception.

Coincidentally I’ve just been reading this passage and following passages (for the nth time) from Matthew, in my daily devotional, but in the First Nations Version to keep me fresh. Gethsemane is about abondonment which church abuse survivors know all too well. Christ went there first, which may be of little comfort, but the gospel we were taught seems a rather more comfortable one.

He went on trial which was the greatest miscarriage of justice in history. It was done at the hands of religious leaders. Sound familiar? Basically they wanted to protect their vested interests and were jealous of our Lord. They flayed Him for bad measure. The FNV describes this vicious torture in a detailed note. They humiliated Him. Unfortunately this is what we can expect.

Watching from a distance, His best friend Rocky betrayed Him. Don’t expect much support from your mates if you step out of line or stand up for something that’s right. People are like sheep. They scatter like faithfuls in a traitors’ castle, if you will excuse the mixed metaphor.

I read this bible story with trepidation because it is exactly like Church life. We know how the story ends, so why do we keep choosing the traitors? Personally I believe it’s very important to call out the Institution for its repeated failures, and I greatly value Robert and his and others’ work in so doing.

‘Procedure-governance- independence-accountability-processes’. Are these words often a subterfuge to avoid our Bishops or Archbishops taking responsibility for covering up savage and satanic maltreatment of innocent men, women, children?

This is a beautiful piece.

Why does God give power to Church leaders out of proportion to their wisdom and sanctification?

Given that he does, why does the Church attempt to defend itself when failures are highlighted?

Instead of admitting wrongdoing, apologising and taking responsibility; they claim they didn’t know what they were doing was wrong or that it was, in fact, what God wanted them to do, or they blame the victims.

Is it because they aren’t prepared to give up the power so they have to find ways to pretend their wisdom and sanctification is commensurate with it?

I am astounded that in the wake of Smyth, Fletcher, Fletcher etc etc; Conservative Evangelicals still have the audacity to claim they are the segment of the Church who are most submissive to the authority of Scripture.

Which part of the Bible were Iwerne/Titus Trust faithful to when they twice failed to take responsibility for the abuse they facilitated?

What sort of moral compass were they following?

Maybe they took their moral compass to the North Pole and tried to follow it there?

But are a great mass of Anglicans deceived? The real inference, from atrocious major abuse scandals emerging, is how BAH (bullying-abuse-harassment) of minor to major degrees is tolerated, is covered up and is endemic across our whole Church. When we read about Smyth and Pilavachi, should we be asking if a great mass of everyday maltreatment of people is still barely noticed?

Yeah, sigh. I can’t imagine I will ever go to any church again because I think it is impossible for them to be safe places. Due to the gap between power and wisdom/sanctification.

People do clearly benefit from Churches, it isn’t all bad.

I think that can make it harder to see the bits that are evil though when it is all so mixed up together.

There is also what I see as well intentioned spiritual abuse. Hard to spot because of the sincerity of belief.

I keep thinking of the section in 1 Corinthians 3

12 If anyone builds on this foundation using gold, silver, costly stones, wood, hay or straw, 13 their work will be shown for what it is, because the Day will bring it to light. It will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test the quality of each person’s work.

The problem with that reveal is the God isn’t going to do it for a long time.

So I think all Church buildings (spiritually) are not up to building regs in terms of using the wrong materials in part (as above).

The stones that are Jesus are still going to stand but the rest will be burnt up.

Unfortunately the parts of the church that aren’t Jesus are part of the structure, it’s extremely hard to see which bits are Jesus and which aren’t.

The fact that some bits are Jesus , I feel gives a false sense of security and makes it hard to question the bits that aren’t.

Yes, disregard for people, and reverence for buildings and bishops, continues to do untold damage to the Church. To attend a multi-denominational midweek prayer meeting, led by the lay members themselves, and without a collection plate in sight, works very nicely for me. A Church cafe can be a good feature to visit, because there is an immediate integrity present about how people are being treated. If the food and welcome are good, then people keep paying and coming back. Lots of Anglicans attend, and contribute financially to a building or clerical wages, but over years or decades start to question how authentic the whole official Church game actually is. Sad when people see the cobwebs and dirt. But it can be the door to a more authentic spiritual adventure. The death of-‘buildings and bishops’-Anglicanism represents progress!!!

I’m saddened to hear that you feel that you will never be able to belong to a church family again. However, I recognise the feeling from the last year. My husband and I had worshipped and served in a variety of voluntary roles for 16 years when a disagreement with the Vicar somehow caused a referral for my husband as a “Safeguarding risk”. No investigation asking for witnesses to the conversation was carried out by the DSO despite there being several, as the conversation took place in public. The Vicar’s account was taken as absolute truth, despite inconsistencies and blatant inaccuracies. My statement was ignored as being “biased”. A Risk Assessment was produced which prohibited my husband from talking to “any Church Officer”. The case was then reported to the DBS who immediately sent a “does not meet threshold” letter. During all this time I continued in a voluntary role while being passively aggressively bullied by being denied access to online communication and shunned by Church Officers. After 3 months, we left the church formally and struggled with what our reactions as Christians should be.

Long story short, we began to attend a church where we were married 50+ years ago and we’ve begun to heal as people recognised and welcomed us. We did confide in the leader of this church about our recent experiences and his listening and advice to wait and be patient was exactly what we needed to hear after all the emotional and spiritual churn. We spent time listening to some great expositional Bible teaching and have gradually begun to recover our trust in our fellow Christians. “Trust” has been the biggest casualty of all this.

Now we have found a new voluntary role helping with a Bible study for adults which is proving a blessing to us and, I hope, them.

BUT, I will have nothing to do with the hierarchy at the Dio, as I agree with everything in the post. I have found the Surviving Church blog so useful over the past year in thinking about injustice and forgiveness…thank you so much!

BAH+DARVO=KCJ is a recurrent theme in Anglicanism. ‘Bullying-Abuse-Harassment and Deny-Attack-Reverse-Victim-&-Offender’ equals ‘Kangaroo-court-justice’.

Serious offenders escape but innocent people get attacked. I felt evicted from a ministry training programme after red-flagging or whistleblowing glaring problems to an Archbishop.

What exactly do lots of parishioners or parishes get for their ‘diocesan share’? The £100M-£1000M on Project Spire tells a story. But doolally Bishop Mullally says it’s all fine…………….

“The fact that some bits are Jesus , I feel gives a false sense of security and makes it hard to question the bits that aren’t”.

Absolutely Gill. That was the ever present confusing element in our 40 years in charismatic evangelicalism. We are now “out” (sigh of relief) and only in the past 6 months are we calling out the bad bits and discerning the difference. When you are in the thick of it, it’s nigh on impossible to sort the two out.

Absolutely. The notorious cases are just the tip of the iceberg.

The elephant in the room!

A denomination which covers Pilavachi, Smyth&Co for decades has zero concern about wider or less severe BAH bullying-abuse -harassment.

Everyday Anglicans should now press for zero tolerance of BAH.

Thank you Robert for an excellent eye opening article.

That the church can’t stop for one moment and say hold on we have failed and failed again. How can we start again in the garden of Gethsemane without failing Jesus?

Acceptance, accountability, admittance is needed.

https://www.private-eye.co.uk/pictures/special_reports/shoot-the-messenger.pdf

PRIVATE EYE article on how NHS medical whistleblowers get disposed of, which makes interesting reading, and possibly bears a resemblance to Anglican Church BAH (bullying abuse harassment).

Thank you, Robert. You have given a clear theological framework to what I was trying to say in my ‘Survivor’s Response to the Archbishops’ Pastoral Letter’. It was published here what feels like aeons ago, after IICSA had finished its first set of hearings into the C of E. We have different archbishops now but nothing has really changed and nothing has been learned.

You refer, here, to-‘Survivor’s Reply to Archbishops’ pastoral letter 25 March 2018-I am guessing?

Yes

I do worry that many of these comments present such a negative view of the church. Of course we are ‘frail earthen vessels and things of no worth’ but we have been entrusted with ‘treasures, that ay shall endure.’ We know that the church is not perfect as Article 26 implies, but that does not mean we should rubbish everything. I think of my own liberal catholic church with its slightly reduced post Covid congregation of about 100. They come to worship God, hear the word preached and expounded and share in the Holy Sacrament. If you were to ask most of them, they would say that they come to get something, even if at the lowest level, it is an opportunity for human company. What ‘the getting’ actually is, to me, should be left to the Holy Spirit. If church going is reduced to survival we perhaps need to echo the 19th century Revival hymn: ‘Hold the fort, for I am coming…’ Maybe 2026 can become a year of Positively Thinking Anglicans.

Does Article 26 specifically refer to the efficacy of the two sacraments not being damaged by a heretical or unbelieving minister? It’s possibly not useful in the context of this discussion. The most positive thing which could happen to Anglicanism in 2026 is for our Bishops and Archbishops to finally respond to hidden abuse. Our Articles of Religion do not encourage veneration of relics. Yet we have a paedophile priest buried close by a door of the Irish national Primate’s Cathedral seat, beneath a grave ending PRIEST SHEPHERD FRIEND. That really is shameful by any stretch of the imagination. But will the Archbishop react positively, or just ignore a rotten crisis staring him in the face? The victims, whistleblowers and witnesses, who comment here on this site, are some of the most positive voices within Anglicanism. The most negative thing the church can do is silence and ignore victims or whistleblowers. Our Bishops are good at that!

The use of the “psychology” of positive thinking does rather date us. It arose and became popular in the post war decades, particularly the 70s I believe. It does of course have a beneficial side, for example the deliberate recognition of good things around, and appropriate gratitude for them.

However “positive thinking” can become a facsimile for pretending. Pretending that there are no problems and everything is rosy in the garden. This was strengthened in ww2 and in the austerity aftermath, and had short term survivalist benefits, but long term and generational dangers. These were ignoring obvious signs of our own and community ill health, like overlooking an unexplained lump, or bleeding. The cumulative effect of this averting-our-eyes has had enormous and deleterious effects.

Testimony from myself and others indicates that recovery from serious depression is possible in spite of the state of the Church. Moreover, and speaking for myself, I live very positively but am able to critique what I regard as ecclesiastical malevolence, yet remain in a healthy state, physically, mentally and spiritually (in my opinion obviously).

Appeasement of those who don’t want to hear us anymore, I don’t believe will help them. Current events on the global stage tend to support this view.

Meeting for ‘company’ maybe a worthwhile activity but distinguished writers such as Earl Hopper (2003) might see this as an “aggregation” where people are together but not really relating. Certainly this was my own experience where, upon leaving, discovered I had almost no friends at all there, despite extensive prior involvement. COVID 19 also gave us some more general empirical data which (again in my opinion) support my views.

It’s time to be realistic about where we are.

It’s time

John, many of us would agree that a lot of genuine worship and good work goes on at parish level. There are, sadly, also sometimes abuses at parish level. But the real problem with the C of E is at the senior level of both clergy and lay administrators – and there the rot is extensive and serious. That has been demonstrated time and time again by IICSA, many reviews, and most recently by the Charity Commission. Those of us who love the C of E can’t pretend otherwise. It won’t help.

1990’s Roman Catholicism discovered how hiding BAH (bullying-abuse-harassment) does vast damage over the longer term. But Anglicans, especially senior leaders, have not learnt this lesson. Ian Elliott’s pithy comment, in an early chapter of-‘Letters to a Broken Church’-exposes this crisis.

A strange providence intervenes at times, but are our bishops and archbishops awake to it when decades of cynical abuse cover-up emerge? Canon Billy Neely (a child abuser) rests in a grave plot by an entrance to the present Irish Anglican Primate’s Cathedral seat. But has the Irish Primate formally apologised for the Church abuse cover up, or come up with any positive plan of response?

Or does Ireland’s Archbishop John McDowell see no irony in the ending PRIEST SHEPHERD FRIEND on the paedophile’s gravestone?

Thank you Robert for such an important article. I will now read Marika Rose! As a survivor who speaks publicly, I’ve certainly experienced what you describe so powerfully, the resistance to acknowledging the failure and the harm caused, the rush to shut down and not confront or sit with the truth. How often are survivors told we should move on, accept closure?

So many reviews have identified that theology and culture are the problem. Some readers may already be aware that the joint working group of NST and Faith & Order Commission are just starting work on scoping a theology for safeguarding. This involves survivors, theologians and safeguarding professionals working together. It’s vital work and I really hope that it can be a catalyst for change. The conversations here are one of the important sources to inform that work

As a recently appointed Safeguarding lead over our local benefice (3 parishes) I am deeply grateful for this article. To have a theology of vulnerability, failure and risky truth telling (and letting the “chips” fall where they may) is the missing piece in the spectrum of our corporate responses to when things go wrong. Having gone through many hours of training, reflective writing and attending seminars – two things were evident:

1. leadership behaviours were given little time as causal elements of toxic culture, and

2. no time at all was spent on thoughts of institutional vulnerability. Just lots of procedural mitigations and a weak theology around why safeguarding is “gospel work”- not that I believe otherwise but to use that as a biblical underpinning to justify process and risk assessment rather than a wholesome and “gethsemane-like” approach to incidents informed my thinking about how we could this better.

Still processing, but what a breath of fresh air reading this has been. Thank you Robert.

ABC News In-Depth carries an Australian Anglican story: ‘The Anglican Bishop who refused to turn a blind eye to institutional abuse | Compass’. The YouTube film runs to almost half an hour. But the punchline is possibly at 12-13 mins into the film. We naturally gravitate, at least a great lot of the time, to shorter YouTube films, or to briefer snippets of written correspondence in our information loaded age. But this YouTube film is most fascinating, and maybe worth sharing? Thanks to the author and follow up contributors here on SC. A most fascinating sequence of discussions……