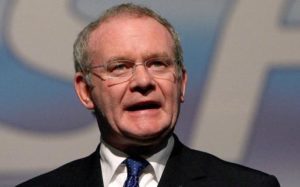

The death of Martin McGuinness on Monday has raised predictable passions among people of all persuasions. Some remember him merely as a fanatical murderer, having a nihilistic contempt for his victims. Others remember him as a key player in the promotion of peace and reconciliation within Northern Ireland. It is hard to know which side is telling the deeper truth about this man. It would be tidy from a Christian point of view to be able to tell a story about how McGuinness had had some conversion experience which led him to participate in the peace-making process. By contrast some have suggested that he had a greater interest in keeping out of prison than in making a fundamental personality change. To survive as free man, he had to make himself indispensable in the Good Friday peace process. I for one do not offer a judgement or opinion on these matters. I merely observe how difficult it is to know the truth about a man’s inner soul based on an observation of the actions of his life.

The death of Martin McGuinness on Monday has raised predictable passions among people of all persuasions. Some remember him merely as a fanatical murderer, having a nihilistic contempt for his victims. Others remember him as a key player in the promotion of peace and reconciliation within Northern Ireland. It is hard to know which side is telling the deeper truth about this man. It would be tidy from a Christian point of view to be able to tell a story about how McGuinness had had some conversion experience which led him to participate in the peace-making process. By contrast some have suggested that he had a greater interest in keeping out of prison than in making a fundamental personality change. To survive as free man, he had to make himself indispensable in the Good Friday peace process. I for one do not offer a judgement or opinion on these matters. I merely observe how difficult it is to know the truth about a man’s inner soul based on an observation of the actions of his life.

Another figure from the other side of the world attracting both praise and blame is the leader of the largest church congregation in the world. This congregation is found in Seoul in South Korea and the leader’s name is David Yonggi Cho. I have recently been reading about the success of this church and the remarkable state of Pentecostal religion generally in that country. Cho’s genius was to discover how much a church can grow when it adopts a cell-like structure. Joining a cell of around a dozen people enables the individual to belong in a way that is impossible if the main Sunday gatherings consist of thousands of people. The small cell keeps membership intimate and personal and thus it fulfils the social as well as spiritual needs of the members. The cell structure is of course a brilliant solution to the problem of the mega-church, but it has at least one severe weakness. It will only work when the cell structures operate in precisely the same way. There is no room for innovation or development. Everyone, both leaders and led, have to conform to the teaching, the beliefs and the vision of the leader. That overriding ethos will normally conform to an ultra-conservative fundamentalist form of Christianity. It is hard to see how this pattern would fit in with the more creative and fluid structures we associate with denominational patterns. Here development and creativity keep everything somewhat untidy and messy. There is normally little attempt to exercise too much in the way of authority and power. A cell structure would, for instance, never work successfully in the majority of Anglican congregations in Britain.

Returning to South Korea where all this cell idea began. Yonggi Cho began his church with five members but later, thanks to the cell structure idea he later had charge of a congregation numbering no less than a million members. There are I believe some cultural reasons for this kind of church growth being possible in this area of East Asia, but that is for another discussion. What we have to draw attention to here is the way that something as successful as Cho’s church became recently a victim of corruption and financial abuse. The sums of money which were misappropriated by Cho and his son were simply vast. Cho’s son has gone to prison for four years and Cho himself was given a suspended sentence of three years for his part in an enormous financial scandal. What are we to make of this fall from grace, which incidentally has only made a small dent in the numbers attending the church in Seoul? Are we to see the Holy Spirit at work here in spite of greed, financial skulduggery and power abuse? Or do we see a human failure which may have been there right from the beginning which disqualifies the integrity of the whole of this ministry? The question is similar to those we asked about McGuiness but in Cho’s case the fall has come at the end rather than at the beginning of his life. I do not know the answer to these questions. I can only suggest that how we answer the questions will reveal something of our theological perspectives. What is important is that we should never fail to carry on a debate about human frailty, even though we want to believe that some people embody a sanctity and holiness which can never be compromised. There is a tendency among some to put charismatic leaders on pedestals of infallible goodness. This is extremely unhealthy. As I have suggested in other blog posts, leader worship will often have the effect of increasing the narcissism of those so affected and weakening their grasp on reality. Whatever anyone appears to achieve in political or religious life, we must never allow that individual to lose their sense of fallibility. Everyone needs to deal with questions and uncertainties. I have already questioned a church system, such as the cell idea, that can ‘guarantee’ church growth for those who follow a detailed formula. This formula will almost certainly include some highly questionable assumptions about, for example, the status of leadership and nature of the Bible. My experience of struggling for truth in church matters is to see that it will never be tidy. Messiness and uncertainty in church structures will have the benefit of allowing people to grow within an atmosphere of freedom. By contrast formulaic and legalistic church teachings and systems of authority can easily enslave people.

In South Korea, the legacy of Cho will be a mixed one. Alongside an apparent genius who could organise vast numbers of people into a church structure, there is a greedy human being. A capacity to exploit and a genius for organisation seem to have existed side by side. That is one reading of the situation and I am sure others will have a different judgment. I am still reserving my opinion on the life of Martin McGuinness. His legacy is at very best ambiguous and I shall leave it at that. History will also tell whether the legacy of Cho and his attempts to revolutionise the church with his cell structures is a good one or whether it will prove to be flawed. This may be either from his personal failures over money or from his readiness to promote what I regard as an inflexible and harshly fundamentalist version of Christianity.

I was brought up hearing Gerry Adams and others saying it was OK to kill people if they were only English! And listening to Ian Paisley. Who to my ear didn’t sound very different. Hate speech, hardly suitable for those who claimed to be Christian. I have a friend who lost a foot thanks to an IRA bomb. But, as one former president of Israel said, all peace processes involve making peace with your enemy, what other alternative is there? You cannot atone for your past sins by doing something good. I’m sure we’re all grateful that McGuinness et al did make the peace process. I’m not so grateful that he got paid as an MP without ever turning up for work, or claimed benefits while killing people. Fortunately, we don’t have make the final judgement as to his suitability for eternity, we can safely leave these people to God. The same of course goes for those who embezzle from their church, or indeed from anywhere else.

Incidentally, I’m thinking that splitting people into groups for Bible study does make the church better, without making them feel cut off from the rest. And in my experience, there’s no need to utterly control what is said in these groups. Of course, I didn’t belong to a church containing millions of members! But there is a kind of halfway house that can be very good.

There is a view that Cho’s success was primarily due to him adopting a syncretic theology (mixing christian and shamanic worldviews) that is attractive to the Korean mindset.

“If you think you’re standing firm be careful you don’t fall”. Wise advice from Paul, in I think 1 Corinthians. I love Ishmael’s song of it for young people.