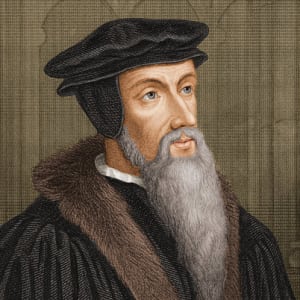

Since I was a theological student I have never been attracted to the theology of John Calvin, the 16th century Swiss Reformer. What little I knew about him and the Puritanism that he inspired, seemed always to put a damper on Christian joy and freedom. In recent weeks, in my attempts to understand the American Right and the onward march of conservative Christian ideas under Trump, I have been forced to consider the man and his doctrines as a way of getting a handle on an approach to the Christian faith for which I have had little appetite. The book that I have recently read, Blueprint for Theocracy by James C Sanford, makes it clear that ignoring Calvin is no longer an option if anyone wants to comprehend the mind-set of conservative Christians and the so-called Christian Right.

The first foundational idea of Calvin and his followers is the idea that God is all-powerful and has control over every part of his creation including humankind. Out of this grasp of the sovereignty of God comes a strong sense that he is all-knowing. In particular, he knows the future of every individual. Predestination, the doctrine that gives all, Calvinists and non-Calvinists alike, cause to shudder, is a logical working out of this idea of God’s supreme sovereignty. This states that God has already decided on those that he has determined to save and those he will condemn.

Calvinism as a system was not adopted without resistance in Protestant Europe. Among the conflicts that raged in the 16th-17th centuries was the debate with Arminius over the problem of what we call free-will. This debate was well aired at the Synod of Dort in 1618-1619. Calvinism was also later refined in the so-called Westminster Confession in 1646. Both these councils, written at times of civil conflict, were to stress the harsher and more rigorous aspects of Calvin’s thought.

The doctrine of the all-seeing sovereignty of God, as set out by Calvin, is one that is, arguably, deeply claustrophobic for those who try to live by it. The notion that a judgmental God governs every event of our life and is in control of every detail, is likely to place a Christian in a permanent state of anxiety and tension. Predestination is also a harsh doctrine and even Calvin admitted this. His response was to quote the passage in Romans 9 where the clay is denied any right to interrogate the potter.

Calvinism is, to summarise, a system which emphasises the will of God above the exercise of human reason. Questioning God is not permitted because mere creatures cannot expect explanations from their creator. Unaided human reason can never be allowed to query this supreme principle.

It does not take much imagination to see how the doctrine of God’s sovereign will being the dominating truth fits well with conservative understandings of the supremacy of Scripture. All ideas about infallibility and inerrancy of the Bible and its central authoritative place in Christian teaching sit alongside Calvin’s emphasis on the idea of the supreme sovereignty of God. Just as the faithful cannot argue with the purposes of the Creator, neither can there be discussion or disagreement with the ‘plain’ words of Scripture which reveal God’s will. The power of human reason is in any case compromised by the fact that human beings are, for Calvin, corrupted by the depravity of original sin. Here he was following the teaching of Augustine. Scholastic theology taught by the mediaeval Catholic thinkers had softened this doctrine so that the schoolmen allowed human reason to have some autonomous power in the scheme of things. Eastern Orthodox thinking also never allowed the human capacity for sin to wipe away the potential for the exercise of reason and the possibility of ‘divinisation’ or transformation by God in this life.

Calvin faced a problem in his teaching of the utter corruption of human nature. How was anyone ever to know anything about God in the first place if human nature was so depraved? He introduced into his thinking the notion of a universal ‘awareness of the divine’. Some, those who count themselves Christian, respond to this impulse. Others ignore it to their destruction. This binary distinction between the followers of God and the ‘God-haters’ is based on a passage in the first chapter of Romans (18-25). It further creates the mind-set that those who respond to God are in one camp while everyone else is somehow an enemy of faith.

The way that Calvin’s binary thinking has been embraced by huge numbers of Christians today has, I feel, done enormous harm to the Christian Church. Calvinists and those who come after them, have got used to thinking that the only way to respond to those who do not share their belief is to convert them, thus bringing the ‘other’ into the circle of their belief system. ‘Preaching the gospel’ will always be understood to be like snatching burning twigs from a fire which would otherwise destroy them. There is no sense that God is already at work in the world or among people who think in different ways. An obsession with sin and destruction meant that Calvin and his followers had (have) little appreciation for the world of the arts and secular learning generally. The 16th-17th century wholesale destruction of paintings, books and statues in Britain was inspired by such Puritan/Calvinist ideas. The mediaeval church buildings in England survived for the most part; in Scotland, by contrast, the old worship buildings were, for the most part, deliberately destroyed in the frenzy of a more thorough-going Calvinist Reformation. In the whole of Scotland only one small section of stained glass from before 1500 survives to this day.

Calvin, to his credit, did seek to apply what he believed about God to the world of civil affairs. He gave 20 years of his life trying to work out the principles of ‘theocracy’ in the city of Geneva. For Calvin, God was concerned for the detail of civil government and the administration of justice. By modern standards Calvin’s theocracy was, however, experienced by minorities as a tyranny. Any independent thinking, including the development of the scientific method, always has a difficult time in such theocratic settings. Linking ‘truth’ only to propositions found in Scripture made it difficult for the scientific method to evolve. The contemporary hostility to Darwin and the study of Climate Change among conservative Christians in the States can be traced back to the religious hostility to secular knowledge encouraged by Calvin.

The values of contemporary Christian liberals, which include tolerance, freedom and the ability to live with difference, are principles that are sadly opposed by the elaborate systems of Christian thinking based on Calvin and his ideas. Those of us who value the principles of this liberal way need to be better informed about his system of thinking. We also need to be ready to resist it when it tries to shut down our desire to think about Christianity and share its insights from quite different perspectives.

Well, I didn’t know a whole lot about Calvinism or Eastern Orthodox ways of looking at things, so I found that very interesting. I was brought up in what is probably a Calvinist type church, and still see myself as an old Puritan! I like plain churches and so on. I’m thinking also that I can see why so many people of my acquaintance go for Eastern Orthodox style worship.

I still think of God as power. Well, you know, the creator of all that is! But as I no longer believe that Scripture is that easy, and have no problem with science, (the truth will set you free) I guess I’m not into predestination nor original sin either! Fascinating stuff. Thank you.

First of all thank you Stephen for this article on Calvin, it’s not so often that he is looked at today which is a pity because he was a profound thinker even though we may not always agree with him. Part of the problem is the expanse of his writing, he didn’t suffer greatly from writer’s block! There are different streams that flow from the Reformed movement as with Anglicanism but of course we all like to think that that our stream must be the ‘right one’. Stephen Anderson said “we all agree with balance in the Church, the problem is we thing we have it.”

You did identify the heart of the matter as lying in the tussle between human reason and the sovereignty of an Almighty God. “Can you by searching find out God?” (Job 11:7) puts it in a nutshell and indeed we have to say that there is no way unless God takes the first move that we can find out about him or relate to him. It was this emphasis that the reformers pushed down into the foundations of ecclesiastical life and which we still live by in the sheer wonder of how a gracious God can have mercy on miserable sinners like us who, as the old general confession says, “have no health in us”. Total depravity doesn’t mean that we are all as bad as can be but that there is no part of us that isn’t affected by being fallen human beings.

As Bach closed all his music “Soli Deo Gloria” (to God alone be the glory).

As usual I want to put on my “evangelical” hat and protest – a bit….

I do agree that this sort of binary true/false thinking that Stephen mentions is potentially dangerous. If anyone says to you “believe it because it is true and I said so” – run – very fast!

But some of the best “Reformed” (Evangelical code for Calvinist) thinkers definitely do not do or say that! Indeed I have heard of one contemporary theologian of that persuasion who often says – “Don’t believe it because I said so, look in the bible and decide for yourself”

But this binary thinking is not coming from Calvin. It comes from Aristotle from his law of contradiction. Aristotle believed that in a contradiction, if one thing is right, the other is wrong. This binary logic spread through Augustine. Calvin took it on board it seems unquestioned. Much that we call Calvinism is in fact Augustinianism.

To the post-modern thinker this true/false thinking makes no sense. Hence the rise of new evangelicals espousing “open theism” which is a post modern approach to the issue of determinism and predestination.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_theism

I agree with Stephen that binary thinking has the seeds of dangerous spiritual power abuse, but so does the anglican doctrine of the priesthood. And I am not saying this as a dig at Anglicans. I am a Baptist, but I came to faith as an Anglican, and cherish those spiritual roots.

Any system that vests too much power in people is potentially dangerous.

So I’m with the last phrase from Leslie – a very common phrase one hears from Reformed (Calvinist) thinkers….

Soli Deo Gloria.

I am sure we can chase the origin of ideas back and back, but it does seem appropriate to see Calvin as starting a new trend. Nobody starts with a fresh sheet totally and this will apply to any theologian. But I think we can say that Calvin is more of an innovator than many among theologians of his time. There are bound to be also strict Calvinists and gentler versions as in any school. As you say Dick binary thinking among Christians is a problem. It does not become right or wrong according to whether it stated with Augustine. It just is a problem for theology generally whenever it appears. I think we can say that binary thinking comes out of psychology as much as it does philosophy. Either/or thinking to me is lazy thinking. That is a point of view.

Stephen, you say that ‘The way that Calvin’s binary thinking has been embraced by huge numbers of Christians today has, I feel, done enormous harm to the Christian Church. Calvinists and those who come after them, have got used to thinking that the only way to respond to those who do not share their belief is to convert them, thus bringing the ‘other’ into the circle of their belief system. ‘Preaching the gospel’ will always be understood to be like snatching burning twigs from a fire which would otherwise destroy them. There is no sense that God is already at work in the world or among people who think in different ways.’

I’m interested to know whether you think mission still has a place? And if so, what is it meant to achieve?

I understand that there is a real philosophical and theological discussion around binary and non-binary thinking but I think we would be remiss if we were not to also admit that, rascals as we are, what we want to be the case plays a large part.

Thee is a lot of binary vs non-binary thinking that goes on on the football fields.

By the way I’m a binary thinker when I go into the Newsagent – I want the ‘right’ change. Toddlers are the best non-binary thinkers, little barrack room lawyers that they are.

Janet. Mission is a big topic but the short answer would be to suggest that that my task is not to make anyone a clone of myself but to allow them to encounter God in some way and then follow where that journey may take them. I don’t ‘convert’ people to save them from hell, though that may happen. I invite them to faith because I believe that will give them a richer fuller life. I want them to know joy, peace and freedom not fear and dread. The Calvinist spirituality has been a path for some to spiritual anorexia nervosa to quote one book I have read.

Thanks Stephen, that makes a lot of sense.

My father was a Calvinist and I attended a Calvinist church as a student, so that is a big part of my background. Incidentally, Gordon Rideout was a Calvinist too. My father said he adopted Calvinism because he found it to be the most intellectually consistent theology; I have come to see that it is just too closed a way of thinking to do justice to the complexities of life and the mysteries of the world and God. I prefer something more organic.

It’s said of Calvinists that their Trinity is Father, Son and Holy Scripture. That nicely edits out imponderables like an unpredictable Spirit, and any suggestion of the feminine in the Godhead.

Stephen, I would want to expand on the simple “I would invite them to faith”. I always want to ask people who say they have great faith, “faith in what?” If I were to spell out my own answer it would be something of the order of faith in God (i.e. that there is a God and worth trusting) and that he is known through his hidden Word in the life and history of the Jewish people (as revealed in the Old Testament) and incarnationally in his revealed Word, the person and work of Jesus Christ.

Dear Stephen. thanks for an interesting article. You state that you know little about Calvin and Calvinism so let me fill you in on some of the background, an area that has seen a huge amount of recent study by historians. Like all of us Calvin made many mistakes – the one that is always brought up is the execution of Servetus. But in general, by the standards of the time, Calvin’s Geneva was a relatively tolerant place and it was certainly not a theocracy. In fact, Calvin was in a perpetual state of argument with the city rulers, who many times ignored him or interfered over his head in the church. Ironically enough Calvin was a big advocate of rights for women – not by the standards of 2018 obviously but by the standards of the 1540s. Violence against women, in particular, was actively punished. There was one famous case – a MeToo moment – where a pastor was accused by a servant girl of sexual harassment Calvin intervened and upheld her complaint, even though the disagreement within the council of pastors became so sharp that Calvin himself was asked to leave the group while the case was discussed. Calvin was of course in general on the side of the oppressed because the pastors he was supporting in France were being persecuted imprisoned and executed. Calvin’s Geneva was the refugee centre for people fleeing violence. Nor is it true that Calvinist have discouraged science – very often they have been at the forefront of this. Historians of early science disagree about this but even critics of Calvinism would hold it had a weak but positive influence, whereas many other historians would suggest that Calvinism opened up a huge range of lines of scientific inquiry. Nor is it true that Calvinists were against Darwins’ ideas – I recently heard a lecture on exactly this which showed that most leading Calvinists were not hostile. It was only when Darwin’s ideas were weaponized by Huxley much later that the battle lines were drawn. many Calvinist today see no contradiction between Calvinism and Darwin, let alone science in general. You can read more about both issues in two recent books ‘ Calvin’s company of pastors’ by Scott Manetsch which is about everyday life in C16th Geneva and “The Penultimate Curiosity’ by Andrew Briggs about the role of Christianity in encouraging science. I would dispute also the statement “The values of.. tolerance, freedom and the ability to live with difference, are principles that are sadly opposed by the elaborate systems of Christian thinking based on Calvin and his ideas”. If we mean are Calvinists theological liberals the answer is obviously no (by definition). But do and should Calvinists promote liberty of freedom of speech? I would hope the answer is yes. Freedom of speech means surely having friendly discussions with people we disagree with? what about “mutual flourishing”? Finally, I do find it highly ironic that the rule seems to be “tolerance and respect to all – except of course those dreadful…

Well said Jeremy – I like your progression – but sadly there is a word limit on this blog – so please enlighten us as to whom the dreadful are!!

And if you can be brief and succinct it will help us all.

many thanks for your kind comments. excuse the length! the lost word was of course “Calvinists” 🙂

Thank you for your contribution Jeremy, a useful rejoinder about Calvin and Calvinists, however you should note that the name and word have passed into ecclesiastical swear word vocabulary and when that happens it is very difficult to arrest the process. I wish we could with many words.