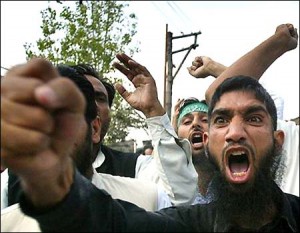

This past month we have had the appalling story of a Pakistani father who organised the stoning of his own daughter in the name of ‘honour’. She had committed, in the eyes of the family, the unforgiveable crime of marrying someone who was not approved. In this action we see various things at work, some of them not so far distant from our own culture.

This past month we have had the appalling story of a Pakistani father who organised the stoning of his own daughter in the name of ‘honour’. She had committed, in the eyes of the family, the unforgiveable crime of marrying someone who was not approved. In this action we see various things at work, some of them not so far distant from our own culture.

In the first place there was in that father a overriding of a fundamental human instinct to preserve one’s offspring. That instinct is imprinted in animals of every kind. It is indeed a necessary instinct for species to continue. Fathers do not always contribute to the nurturing of their young and we have all watched the female polar bear wandering the snowy wastes protecting one or two cubs to the best of her ability. Absence is one thing but for a father to destroy his own daughter means that a powerful instinct or taboo has been overwhelmed by something else.

What is it that could allow a human being to defy not only morality but the primal instinct to preserve and procreate into future generations? How could a potential grandfather destroy the descendents that at one level are the sole purpose for his existence? That it can be suggested that the answer is somehow religious is a deeply troubling thought. How can religious belief ever justify killing a daughter and grandchild not yet born?

To offer even a partial answer we have to return to the aspect of religious faith that has been discussed before on this blog. Religion is the force that connects the individual to other people and their surroundings and gives them a place in an otherwise fragmented universe. That is the meaning of the word ‘religio’, a binding up or connecting. The infant is born into a world where nothing make sense and there is plenty to frighten and scare the person on their own. The only strength comes when we bond together with others so we learn to depend on their strength and not rely just on our own. The ‘I’ becomes part of a ‘we’. In most societies today, the security of tribal or group membership allows a single person to feel reasonably safe because he or she is protected by the force of numbers. The tribe or group will of course make demands of the individual in return for this protection. The tribe will demand that the individual member conform to the mores of the tribe, whatever rules and customs have been set out over the centuries. In most cases, these customs enhance community life and make it possible for the individual to navigate safely through life and remain a respected member of the group.

The crisis comes when the desire to be part of a ‘we’ culture demands a price that is too high. We see that in the cults that the urge to belong encourages the members to sacrifice their moral integrity in some situations. Whether they engage in ‘flirty fishing’ or even murder in order to belong, their desire to be part of ‘we’ group has destroyed the essence of their morality. In the Pakistan episode we see a facet of Islam that is falsely saying to its followers that there is such a thing as ‘honour’ which is higher than morality, humanity and instinct. We can imagine something of the pressures put on individuals like the murdering father in Pakistan. Simultaneously we have to be quite clear that there is such a thing as a morality that transcends all religious systems. The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights offers us a good start. It sets out certain principles which should be acceptable to people of every faith and none. The massive misogynist culture that infects many religions, including our own, is something that needs to be constantly challenged by those inside and outside these systems. The heinous crime of a father killing his own daughter can be seen not as simply as an individual act. It is a crime that has to be laid at the door of every religious leader who failed to challenge contempt of women by men and allowed this infection to spread across the globe both within and outside religious systems.

Those of us who practise a faith have to recognise that the word ‘religion’ is not necessarily a force for morality or goodness. Forces like politics, unabashed power games and blind prejudice can easily creep in to infect it. It is important for religious leaders of every tradition to seek to purge away the possibility for evil to creep into religious practice. It is tragically hard to see how such events, the killing of a daughter by a father, will be stamped out until all religious leaders have glimpsed the idea of a universal morality which binds together the whole human race. Perhaps the compilers of the Declaration of Human Rights have something to teach the leaders of religions that morality and human rights are not protected by faith systems. Religions need to rediscover morality and human rights all the time and not assume that the faiths of the world are the guarantors of truth, morality and goodness. In the case of the Pakistani father, that failure is all too tragically evident.

Interesting analysis, Stephen. Thank you