One of the advantages of growing older is that I have many more memories to recall than those that are available to a younger person. Recently I found myself thinking back to my days as a member of Keble College Oxford in the mid-60s. Our Warden, Austin Farrer, was a highly eccentric individual, a priest steeped in a version of Anglo-Catholicism which, even then, seemed somewhat old-fashioned. I was in the college choir, and it was said that the organ scholar had been encouraged to choose mass settings with lengthy versions of the Agnus Dei to make space for the Warden’s devotions at that part of the service. I got a further insight into these devotions when, at weekday services, I sometimes acted as a server. The devotions lasted just as long in these said services, and they were distinctively accompanied by much tapping of the chest. The words that were offered sotto-voce in prayer seemed to be prayers and sections of the psalms in Latin. This added to the strangeness and solemnity of the occasion.

The act of coming before the altar to declare one’s unworthiness of God’s mercy and grace is evoked for me by this memory of the distinctive sound of chest tapping all those years ago. I do not use Latin nor chest tapping but I picked up from the Warden something about the importance of humble reverence before the consecrated sacrament. This has never left me. A single word surrounds this distinctive Anglo-Catholic piety in the presence of the sacrament – unworthiness. The prayers of approach all seem to repeat this sentiment, ‘I am not worthy to receive you’.

This sense of unworthiness in Catholic piety is something that I am not qualified to speak about with any expertise, but I think it would be true to say that it is a key sentiment within Catholic devotional practice. Alongside it comes the distinctive Catholic concern for purging of sin following confession, public or private. Whatever we individually think about sacramental confession these days, the aim of the practice seems to have the worthy goal of increasing self-knowledge in the individual penitent. A major problem for Christians and for everybody else is a common tendency to have false ideas about one’s own personality and character. The ancient Greeks took very seriously the importance of learning the truth about oneself. Today we are far more likely to go in the opposite direction, creating an image of ourselves which we think is appealing to others, but which may not be engaging much with our core selves. The narcissist, about whom we are constantly speaking on this blog, is a prime example of this behaviour taken to an extreme. In its fully developed version, narcissism is all about show and no substance. The people around the narcissist are expected to collude with this false image put out by the afflicted one. These colluding ‘friends’ are kept in place by a combination of the threat of the narcissist’s irrational anger and the use by him/her of flattery and other forms of manipulative behaviour. The whole thing ends up as a kind of dance around the narcissist. One thing that has effectively been banished is any true self-knowledge, the kind that Catholic forms of confession were supposed to uncover and then respond to appropriately.

It is, of course, not just Catholic traditions that teach about the work of self-knowledge, repentance, and forgiveness. Words used by Christians in every tradition, like contrition, mortification, remorse, and sorrow all play a part in describing the feelings of a convicted sinner. There is, however, a danger of developing obsessive behaviour in this task of self-examination. Here we merely note the existence of a pit of despair where some Christians find themselves in their efforts to be freed from sin. Clearly some boundary has been crossed where healthy self-knowledge has changed into unhealthy morbid obsessive feelings. It would be the task of a spiritual director to guide the penitent out of this place of despair. The opposite failing is that of an over-optimistic detachment from the core self, where there is always the potential for fallible sinful behaviour. This remains the commoner scenario. What is true of the individual is also true of the group. We have often noticed occasions when whole swathes of Christians have somehow been unable to identify the enormity of sinful behaviour taking place in their midst. Typically, an influential but flawed Christian leader has gained a controlling influence in this constituency or network of churches. Their importance or charismatic status somehow means that everyone expects them to be beyond the possibility of wrongdoing. Charisma and the dynamics of narcissism have then skewed the ability of large groups of people to see evil and to recognise that they and their leaders are capable of the most dreadful forms of damaging behaviour.

The classic text in the New Testament about self-examination and self-knowledge is the passage about the tax-gatherer and the Pharisee. This audience will know the story well. It was the tax-gatherer who stood afar off and ‘beat upon his breast’ who left the Temple ‘justified’. The behaviour of the tax-gatherer reminds one of Psalm 51 where there is confession of sin without any attempt to make excuses or mitigating explanations. ‘Against thee only have I sinned and done evil in thy sight….. thou requirest truth in the inward parts.’ The Bible does not give any encouragement to us that we can bury our failings, either by excuses or by observing a silence that would somehow magically make the whole thing go away.

In the aftermath of the exposure of the Smyth/Fletcher scandals and the publication of Graystone’s book, I looked for some response or reaction from those Christians who acted as the complicit bystanders and enablers of Smyth and Fletcher. Surely, I thought, there will be at least one person who would publicly recognise the way they had been caught up in a cult-like movement which made them, even indirectly, complicit in the evil? When sin on an industrial scale is exposed, one looks to some bystanders to be able to stand up and say: ‘Help! I was blind, misled or bamboozled into thinking that all was well. It wasn’t and what can I now do to help put things right?’ That voice of the concerned but guilty bystander has been completely missing, at least in public. There have been no cries of: ‘If only I had known earlier then I would have worked to support and love the victims of these appalling evils.’

The silence of leaders in the Church Society/ReNew/Titus constituency, in responding to Graystone’s revelations, has been deafening. One can only suggest that it seems a sensitivity for recognising evil, individual and corporate, has been somehow blunted for many Christians. Is it that the topic of sin in this conservative culture has become so bound up with the issue of sexual partnerships, that the network no longer has the energy to face other more serious failings, like those of ignoring the needs of a wounded neighbour? Is concern for reputation, power and money so much more important than following the example of the tax-gatherer in the Lucan passage? It was striking that one leader, who could, a long time ago, have done so much to stave off the pain of countless others, chose, with his supporters, to attack Graystone rather than showing an ounce of self-scrutiny or self-examination for his part in the whole narrative.

Alongside the failures of the Titus etc network to show evidence of understanding that the Christian faith involves acknowledging fault and sin, we also have the tone-deaf response of the wider Church to the broad range of safeguarding failures. Nowhere among the many apologies to survivors put out by bishops and archbishops do we hear the genuinely remorseful tone adopted by the author of Psalm 51. Rather we hear the PR language of ‘lessons will be learned’, sincere personal apologies and regret. If only the statements from the centre could sometimes convey a real human response of human vulnerability and even brokenness that is appropriate to the occasion. If only these episcopal expressions of sorrow could reflect what we learn of repentance from Luke’s tax-gatherer.

Returning to the memory with which this reflection began, I realise that the sound of the chest being tapped has communicated to me something further about the nature of sin, something which seems to bypass many in today’s church. The gentle smiting of one’s own chest is a symbolic acceptance of each individual’s personal responsibility for sin. This tap on the chest is pointing us back to ourselves and nowhere else. We cannot hide or unload that responsibility on to other people or an institution. In any attempt to remove ourselves from responsibility, we allow evil to fester because no one else is going to own up to it or take responsibility for it. This ‘pass the parcel’ approach to the evil of abuse has created a monster that has been destructive and deeply damaging to the Church. What we and the whole Church need to see and identify with is the tax-gatherer standing afar off who ‘would not even raise his eyes to heaven but beat upon his breast, saying: “God have mercy on me, sinner that I am”.’

I learnt the triple tap on the breast from Archbishop Michael Ramsey. I was so struck by the thought that if someone so saintly was regularly acknowledging his own unworthiness, then how much more a very ordinary Christian like me.

It’s very odd that people who must say the Confession a dozen or more times every week, should be so averse to admitting actual failures when it comes to safeguarding. Most of our leaders are very slow to apologise, and when they do apologise it’s both generic and superficial. As in the memorable phrase, ‘Mistakes were made, but not by me.’

Survivors like myself and Matthew Ineson (and many others) have never had an apology at all. Even when Archbishops Welby and Sentamu were directly asked by Counsel at the IICSA hearings if they would extend an apology on behalf to Matt – who was sitting a row or two behind them – for the Church’s egregious failures in his case, they failed to do so. And immediately lost any credibility they had, and with it any spiritual authority.

Farrer’s memory was perpetuated by an excellent conference in January 2019 at Keble, and the subsequent publication of the talks. We have much to learn from both his personal holiness and the truthfulness and non-partisan nature of his scholarship, which was another side of the same coin. Others questioned the way he was constantly changing the details of his biblical analyses, but what they were watching was a refinement process.

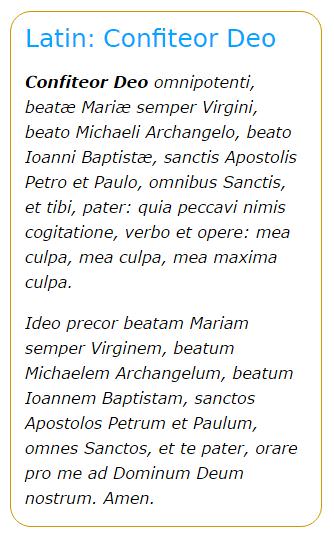

Am I alone in being amazed that despite mentioning so many parties the Confiteor Deo contains no reference to Jesus Christ? Yet that’s key. Confession is vital, but not enough – otherwise what do you say to Muslims?

Also, I’m not clear as to where CS and ReNew, as such, are responsible to answer the charges laid by Andrew Graystone, though certain individuals prominent in them may be. But Titus as a body are clearly in the green eye of the storm.

‘Am I alone in being amazed that despite mentioning so many parties the Confiteor Deo contains no reference to Jesus Christ?’ That does seem very odd. I’m not familiar with the Confiteor, , but the version on Wikipedia ends with a reference to Jesus. Perhaps someone with an Anglo Catholic background can explain the different versions of the Confiteor to us?

I’m puzzled, though, Dan, by your question ‘Confession is vital, but not enough – otherwise what do you say to Muslims?’ What do Muslims have to do with it?

As for Church Society and Renew, when an organisation’s leaders fail to respond properly in a serious case of abuse, or to look after the victims, it’s very much the responsibility of the organisation as a whole.

Well said Janet. Organisations cannot get away with saying that what their employees/ members do has nothing to do with that organisation. When the behaviour includes abuse or harassment of any kind, for example bullying, the organisation most definitely has a responsibility. Whilst church organisations seem to act on stealing or fraud, the tendency is to allow abusive individuals the freedom to abuse.