by Janet Fife

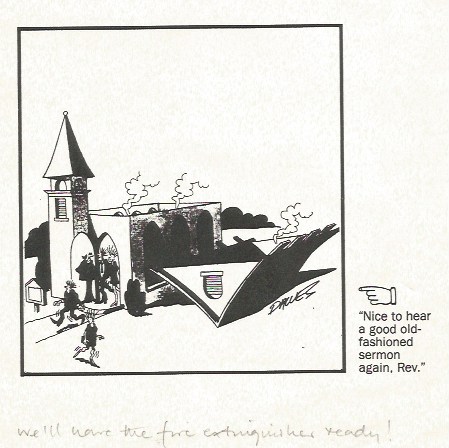

I arrived at my office in the church to find a cartoon taped to my door. It depicted a smoking church, with shaken and singed members of the congregation departing. One of them says to the minister on his way out, ‘Nice to hear a good old-fashioned sermon again, Rev.’ Someone had pencilled in underneath, ‘We’ll have the fire extinguishers ready!’ I can’t remember what text I’d been assigned to preach on that Sunday – I was still a curate – but clearly I’d gained a reputation for preaching some pretty judgmental sermons.

That was part of the tradition I’d grown up in, where preachers ‘dangled sinners over hell’, like the 18th C preacher Jonathan Edwards, or ‘challenged’ their hearers ‘to within an inch of their lives’. It was all done in love, of course: people had to be ‘convicted of their sin’ before they would turn to God. So in all earnestness I would declare that ‘God is not impressed’ by this or that aspect of human behaviour. I knew very definitely what was right and would please God, and what was wrong and would make God angry. Certainty is so reassuring.

It was at some point after that cartoon was left on my door that I sat in that same office preparing a sermon. And an inner voice said to me, very clearly, ‘It isn’t your job to convince people that they’re sinners. That’s the job of the Holy Spirit.’ (See John 16:8.) I saw then that my role was not to convince (‘convict’, in evangelical parlance) people that they were sinners, but to attend to those who were already worried about their sin. To those people I might minister forgiveness, healing, restoration. Or, as often happened, I might reassure them that they had done nothing wrong. I recall one woman, who came to see me who was tormented by guilt and could find no peace. Her offence? On her first ever visit to church she had taken communion, not knowing she ought to have been confirmed before taking part.

Many of us will, at one time or another, have taken part in a social media conversation among Christians where some of the participants refuse to accept that there is more than one valid point of view on a contentious topic. Not content with merely stating their own views, they imply that anyone holding a different opinion is wilfully disobedient to God. ‘The Bible clearly says, x, y, or z, and everyone who wants to obey God agrees with me.’ There is no recognition that faithful Christians might differ as to the interpretation of the Bible or the will of God; no nuance. If others in the discussion quote Bible verses that appear to contradict their stance, they ignore them or explain them away. If opposing arguments are backed up by citing Bible scholars, those authorities are dismissed as unsound or second rate. Nothing can shake their apparently impenetrable assurance that there is only one version of the truth, and it is theirs.

This is not a new phenomenon. St. Paul, writing to the Romans, said: ‘Accept the one whose faith is weak, without quarrelling over disputable matters. One person’s faith allows them to eat anything, but another, whose faith is weak, eats only vegetables. The one who eats everything must not treat with contempt the one who does not, and the one who does not eat everything must not judge the one who does, for God has accepted them. Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To their own master, servants stand or fall. And they will stand, for the Lord is able to make them stand.’ (Rom. 14:1-4 NIV).

The question of whether or not to eat meat may not sound too serious to us, but to first-century Christians living in Gentile cities it posed a serious dilemma. Much of the meat sold in the market came from animals which had been sacrificed in a pagan temple. Therefore, the meat on a Christian’s plate might well have been sacrificed to an idol. To some, knowing the idols had no real existence, this didn’t pose much of an issue. Others felt strongly that it was a risk no Christian should take. This might be that they believed the idols had demonic power, or because the believers had converted from the other religion and were afraid of being lured into slipping back, or for some other reason. For whatever reason, they contended that true Christians ought to make their devotion to Christ alone clear by abstaining from meat. Real Christians were veggies.

I was born in 1953, and in my lifetime the defining issues of ‘soundness’ for evangelicals have included the following: not wearing make-up (for women); not having long hair or beards (for men); not dancing, drinking, smoking, playing cards, listening to rock music, or seeing films; the right beliefs about the Second Coming of Christ, the Tribulation, Rapture, and Millennium; predestination vs. free will; the authority and infallibility of Scripture; eschewing vestments, candles and incense in church; wearing a cross rather than a crucifix; opposing the ordination of women; and believing homosexuality to be sinful.

Some of these are still contentious issues, but the heat went out of others long ago. And while British evangelicals have never been much exercised over dispensationalism and the details of the Rapture, their American equivalents never had a problem with cosmetics. My mother, speaking to a church ladies’ group in the Chicago suburbs in the 1960s, recounted how shocked British evangelicals had been when the Billy Graham team arrived in England in 1956, and the wives were wearing make-up. Unfortunately, it turned out there were several of those same wives in her audience, and they were affronted. That was the last time my mother ever spoke in public.

Anglo-Catholics will have their own shibboleths, as will traditionalists. Observing Ascension Day on a Sunday; the position a priest takes when celebrating; whether ‘virtual’ Communion is valid: almost anything can be loaded with immense and eternal significance. I have known charismatics maintain that everything from paisley fabrics to Body Shop products are demonic and must be eschewed by truly devoted Christians.

Which all reminds me of the therapists’ axiom: ‘The presenting problem is never the real problem.’ The real issue is not eating meat, the infallibility of Scripture, or LGBT people. The real issue is a deep, unspoken fear that God cannot possibly love us enough to accept us despite all our sins and mistakes. It’s a dread of what happens when we die. It’s a (probably unacknowledged) rage that has to find an acceptable outlet when Christians are expected to instantly forgive and forget even the most terrible wrongs committed against them. Or it’s the preacher’s own guilt projected onto others, as with my abusive father or my colleague Geoff, who was outed by the News of the World as ‘the dirty dean of Salford’ after advertising ‘Happily married man seeks sex with no strings attached’.

It took me years, even after I stopped preaching judgment on people, to realise that the eagerness to do so sprang from my buried anger at my father and other abusers. I had grown up among evangelicals who believed that the ‘abundant life’ Christ brought meant we should always be smiling and full of joy. And two vicars had counselled me that I must forgive my father for the abuse; one even told me that if I was still angry after a single session of prayer I must be ‘demonised’. So what acceptable outlet could I find for my rage, other than to condemn those who could safely be regarded as sinners? One of my greatest regrets, looking back over my life, is the people I damaged by doing so.

I wonder if Paul had similar regrets. At any rate he, the ‘Pharisee of the ‘Pharisees’, the absolute stickler for the letter of the Jewish law, writes to the Romans that it is the punctilious Christians who have the weaker faith. This is of course the opposite of what I was brought up to believe. It seems also to be the reverse of what many contemporary conservative evangelicals still believe. The CEEC (Church of England Evangelical Council) has this week issued a video which includes the following statements:

‘If you and I disagree about what the Bible says is good, and what can receive the affirmation of God…we have a fundamental problem.’

‘We can’t agree to disagree on these foundational issues of sexuality and Christian living because Jesus says they’re issues of eternal significance.’

‘This particular issue goes to the heart of what we believe, not particularly because of what people do in their bedrooms, but because of what it says about God.’

The video is, as you will have guessed, about whether the Church of England should be accepting of same sex relationships: but over the years and the centuries the same things might have been said about many another issue which is now not an issue. The speakers will all have been absolutely sincere in their belief that LGBT+ is the most important and defining topic for the Church of our day, but it’s not clear to many of us that they are right. If Jesus said anything at all about homosexuality the gospel writers didn’t record it; and how can affirming gay Christians say anything bad about God?

However, I don’t intend to get into a discussion here about homosexuality; my theme is our tendency to judge each other about decisions which are really between the individual believer and God. We rightly condemn those activities which harm others: slavery, theft, adultery, violence, sexual abuse, slander, and so on. We are right, too, to be truthful about corruption and injustice where we find it. But I now believe that we should be very slow to call sinful those activities that don’t harm anyone else. We don’t know what God is doing in someone else’s life, but we do know that it’s the Holy Spirit’s job to nudge them if what they are doing is displeasing to God. I end by parapharasing Paul’s wise advice to the Romans:

‘The one who is liberal must not treat with contempt the one who is conservative, and the one who is conservative must not judge the liberal, for God has accepted them. Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To their own master, servants stand or fall. And they will stand, for the Lord is able to make them stand.’

Replacing imported and easily unquestioned dogma, with reasoned, nuanced reality-based thinking, has been a lifetime’s work for me.

Behind the dogma fear often lurked. And I wince now at those I hurt with clumsy often stupid but church sanctioned attitudes. Creating and amplifying differences that never really had much if any biblical weight, are the modus operandi of the places I left.

The phobia behind homophobia and other phobias often are fear-based rather than hate-based. But there is plenty of hate too, which never seems to strike anyone as incongruent. But the fear is a deep seated existential terror that they aren’t really different at all from the vast swathes they have designated “unsaved”, and more specifically that if they could admit to themselves their own sexual and other variations, they might themselves not be saved at all.

Lovely post, Janet! Thank you. I remember the attempts to frighten people into the kingdom. I’m sure it never worked. I was mostly just irritated by the use of the word “convict”. Why use secret codes if you’re meant to be reaching out? And that goes for the Elizabethan language in the BCP, too! And you forgot women having to wear hats!

I came across a comment of Christopher Caldwell who remarked that identity politics had, by the Trump years, become the “reconciler-of-contradictions” within the Democratic coalition.” Could this phrase sit also with the Church of England as it struggles with its future ?

Reading the story of Peter’s denial in Luke this morning, for the umpteenth time, I was struck by something I’d never realised before. When the cock crowed and Jesus looked at Pete, I’d always assumed it was a judgmental “look”. An “I said you would” look. And it was written there to show that Our Lord was very accurate with this prophetic/prediction stuff, and it was a dead cert that Peter the rock was actually a confirmed flake, always to be recorded as the one who denied knowing his best friend.

Strangely though this morning I saw it differently for the first time. I think Jesus was looking over to see his dear friend and careful for him, caring to see if he was actually ok, because He knew how badly Peter would feel about himself. In that moment, and of course I can’t be sure one way or the other, but I believe it was a genuine “look” of love. Not of self pity for the betrayal or hostility or any of those things at all.

I just mention this because I believe Janet is spot on with what she writes. Even after all these years I’m learning to see things differently, to realise that old interpretations were just that, interpretations. I also more frequently wonder how much else I got wrong, but thankfully don’t beat myself up too much about that either because I don’t think it’s healthy to, and I don’t think He would either.

Thanks for this Steve, it’s a lovely thought. And you may well be right about the way Jesus looked at Peter.

It’s one of the remarkable qualities of the Bible that however often w dread it or hear it preached on, we can still gain new and unexpected insights.

May I try to explain why the CEEC might take the position Janet describes, though this comment is entirely my own view. I will focus the question on our recently completed Living in Love and Faith (LLF) discussions.

Consider the following quandary:

(i) LLF is looking for mutually respectful discussions within the Church to help us discern a way forward on sexuality and marriage. This is surely right; we need to listen to each other and preserve unity despite our disagreements, if possible.

(ii) Some of us are asking the Government to introduce legislation which may criminalise those who are supporting persons distressed by aspects of their sexuality. That support may include seeing whether the person can move away from an unwanted same-sex attraction if they freely wish to explore doing so. This might include prayer, pastoral care and professional psychological counselling. Change is possible for some, with one example even appearing in the LLF videos! His name is Graham and he is ordained.

In my view we cannot have (i) mutually respectful LLF discussions when (ii) some of us are effectively calling for the criminalisation of their brothers and sisters on matters which are, ironically, directly related to LLF. Persons like Graham may well be left in their distress by legislation implementing a comprehensive ban which goes well beyond stopping coercive practices. The result would very likely be harmful for some, or even worse.

It makes no difference what side of the argument we are on, what our view of Scripture is, or that the General Synod (2017) requested this legislation from the Government. Threats of prosecution undermine the integrity of the whole LLF process.

The ramifications run well beyond LLF. The various Transformation programmes in the Church will be similarly undermined and ultimately our unity cannot survive such prosecutions. Hence, perhaps, the CEEC’s position.

Janet Fife paraphrases St Paul’s wise advice at the end of her article:

‘The one who is liberal must not treat with contempt the one who is conservative, and the one who is conservative must not judge the liberal, for God has accepted them. Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To their own master, servants stand or fall. And they will stand, for the Lord is able to make them stand.’

Assuming her paraphrase opposes those pressing for prosecutions, people like Graham might get the support which they have every right to receive. And if so, Amen to that.

Why might some people be ‘distressed’ by their ‘unwanted’ sexual orientation? Might it be, perhaps, because others have told them God does not approve of it?

In a world of 8 billion people, the category of those not at home with it will not be a null set. It is unreasonable to expect that it will be. But it is especially unreasonable to expect that when simultaneously it is allowed that people may not be at home with something far larger, their very gender. It would be reasonable to expect that the set of those not at home with something smaller and less far reaching would be larger than the set of those not at home with something larger and further reaching.

They may have been told they are XYZ by people who want them in their pool of sexual partners.

They may have tried XYZ and felt alienated or uncomfortable or unwell long-term.

There are so many possible circumstances. Rather than writing people’s autobiographies for them, we should listen to them. They know best – by a large margin – about their own autobiography. And anyway people are allowed to be counselled about anything they choose – who would presume to stop them? And sexual orientation is at times malleable, and often not without roots in circumstance.

Very many reasons therefore, which are not newly given by me but have been oft repeated and therefore need to be interacted with when the subject comes up.

Of course it’s not down to those in the Church to decide the issue, whatever we might think. Secular society decides, as represented by parliamentarians depending on the political risks of such a decision pertinent to their own re-election potentials. Our lobbying, independent of which way, may be counterproductive bearing in mind the disgraceful reputation of the Church with extensive abuse scandals.

Some parts of Christendom are decades behind current generally accepted scientific understanding of sexuality. It’s hard to see how those who disagree with these current painstakingly elucidated views can realistically take us all back into those more archaic positions.

“decades behind current generally accepted scientific understanding of sexuality”

I would be interested to hear a few things here. One would be a quick summary of what this currently accepted understanding is. Another would be a reason to believe that it was any more stable, more useful or closer to the truth than the understanding of, say, 50 years ago (which was, I recollect, radically different). But perhaps the key point to expound would be the argument from how things are (which the sort of thing science tells us) to how things ought to be (which is the question under discussion).

Who decides what “ought” to be? In 50 years my personal answer to this question has shifted radically. I started with answers but now have more questions. What started as orthodoxy has been sifted by the fire of gruelling experience and much of it turned out to be chaff.

I have a friend who is gay. I now believe he was probably born that way and that this is completely normal. He is no less nor more than me in God’s eyes, who looks at the heart of what we are and do, and not at the geography of our body positioning.

I’m reluctant to characterise in a short space scientific thinking, because like sexuality there are any variations. But the consensus seems to be just the above, that people vary and that’s normal and that they should be treated with equal respect. Personally I think this is a massive improvement on 50 years ago, but there is still a lot more work to do on our prejudices.

I know that Stephen does not want this blog to descend into a blog on sex which I am happy with but it does seem to keep getting mixed into the background. Being gay is a multifactorial position, birth and genetic issues being part of it, but we ought not to treat it in similar terms to being black or being white. It is not.

As to the issue of what people think, we ought to be aware in our present age that the cultivation of opinions and of mis(or dis)information is all around us.

An influential book written on the subject of sexuality by a researcher in neuropsychiatry and a co-author, an expert on public persuasion tactics and social marketing, argued that an effect in this area can be achieved without reference to facts, logic or proof…. “the person’s beliefs can be altered whether he is conscious of the attack or not” (“After the Ball” [Kirk and Madsen.] p152-153).

Having read the book a number of years ago a good summary of it can be found here file:///C:/Users/lmslm/OneDrive/Leslie/Homosexuality/After%20the%20Ball%20-%20web%20page.mht

My blog was not about sex, it was about judging others. I’m sure we all have an opinion – or several opinions – on sexual issues. That doesn’t give us the right to condemn others, or sit in judgment, unless what they are doing makes victims of other people; such as sexual abuse.

I wasn’t particularly referring to your piece on the blog Janet, just a a general background drift into the area which often seems to occur and with a sideways slant at any who are not of the ‘progressive’ wing.

I know what you mean about persuasion tactics Leslie. I’ve been persuaded much more quickly than I otherwise might have been by the hypocrisy, and narrow mindedness of certain fringes of the Church, except in the opposite direction from their views. I’ve become determined to root out my own inaccuracies and prejudices and stand up for what I believe to be right.

Bless you Steve, we all need to do that….. and never imagine we have reached the end.

Apologies to any who tried to access the link to After the Ball. IT skills need to be improved! It is

https://www.massresistance.org/docs/issues/gay_strategies/after_the_ball.html

Worth reading.

It’s a very cynical book indeed, amoral. It realises that if you jam a particular point of view enough, people will adopt it regardless of the evidence or lack of it. It even sets a timeframe (the 1990s) wherein this is bound to happen because of known psychological patterns.

It even admits that its project is not connected to truth or evidence.

The idea is that being strongly proportionally implicated in a pandemic makes something a hard sell. Yes. Hence the need to map out a strategy for convincing people, for what you emphasise and what you de-emphasise.

Not quite sure what your last paragraph means Christopher – not a criticism maybe I’m just not ‘with it’.

It is very important not to be liberal, and it is very important not to be conservative. Simply because one must be a truth-loving truth-seeker, not an ideologue. That is elementary, and is the (large) difference between honesty and dishonesty, between imposing one’s personal preferences one everyone else and being maximally evidence-based.

Although you say ‘the heat went out of others long ago’ that is just a matter of fashion, and fashion (being transient) is not a central factor. It would be significant if history went in straight lines, but history has never remotely done that. Which is why one cannot be on the right side of history (as the phrase has it). History never comes to a. (pace Sellar and Yeatman)

Looking back at my previous comment perhaps it was too vague especially as it was referring to a completely different and political issue and institution – the Democratic Party in the US. What I wanted to highlight was Caldwell’s phrase “the Reconciler of Contradictions” which in view of the Archbishop of Canterbury recent book on Reconciliation might have a locus here.

There are plenty disagreements people may have in the Church which may be overcome in a spirit of conciliation but it is becoming obvious that we are not looking at different points of view or understandings but plainly at contradictions. They are not reducible. The only way through such a position is a) one must be right, or b) the other must be right, or c) neither must be right.

The Church of England is still struggling with this position as it tries to reconcile contradictions and not wanting to plump for a) or b) but neither is it happy with c)

Helpful post. Thanks Janet