There was an interesting comment today (Friday) from one of the Times’ columnists, Janice Turner. She was talking about the Archbishop of Canterbury and saying that generally this has been a good year for the Church of England under his leadership. But then she commented that he was given to a ‘simple-minded sloganising’ when he frequently comes out with the expression ‘the good news of our Lord Jesus Christ’. She likens the slogan to something that you hear in a supermarket, an ‘inelegant formulation …..that isn’t very English.’

There was an interesting comment today (Friday) from one of the Times’ columnists, Janice Turner. She was talking about the Archbishop of Canterbury and saying that generally this has been a good year for the Church of England under his leadership. But then she commented that he was given to a ‘simple-minded sloganising’ when he frequently comes out with the expression ‘the good news of our Lord Jesus Christ’. She likens the slogan to something that you hear in a supermarket, an ‘inelegant formulation …..that isn’t very English.’

The columnist has a point; we do hear many clichés uttered in the course of sermons that, when they are left unexplained, are, no doubt, a source of confusion for those not initiated into this sort of language. In this particular case there is some unpacking to be done. I would however begin by saying that the expression the ‘good news of our Lord Jesus Christ’ is not one that I personally would ever use. But let me begin by giving an explanation of what I believe the ‘good news’ of the New Testament is in fact all about, taking, first, the perspective of the Synoptic gospels. Right at the beginning of Mark’s gospel, we have that memorable sentence (chapter 1. 14-15) when it is said of Jesus that he ‘came into Galilee proclaiming the Gospel (good news) of God’. The Greek word for Gospel here is often translated as good news, so we can regard the English words as identical in meaning. What is the good news or gospel as Jesus understands it? The passage goes on to explain what this good news is all about. Jesus is reported to say, ‘The time has come; the kingdom of God is upon you; repent, and believe the Gospel’. We would be correct in taking the natural meaning of these words and see that the good news is closely identified with whatever Jesus means by the ‘kingdom of God’.

I can still remember the moment in my theological studies when it became clear to me that the understanding of this term ‘kingdom of God’ was the key to understanding much of what the synoptic gospels were about. In particular it was a term that was the key to unlock the meaning of the parables and thus much of the teaching of Jesus as a whole. Recalling a lot of reading from almost fifty years ago, I can remember how the writers like Norman Perrin and Joachim Jeremias opened up the meaning of both ‘Good News’ and Kingdom of God for me. The overriding idea of these terms was that Jesus believed that in his words and actions, God’s rule or activity was becoming visible. Those who attached themselves to his ministry could encounter God reaching out to them through the acts of healing and forgiveness that Jesus performed. Among the most vivid announcements and outworkings of this Kingdom were the meals with the ‘tax gatherers and sinners’. Here both forgiveness and outreach to the outsider were being powerfully enacted. The Lord’s Prayer itself was a prayer for the kingdom of God to come into the here and now. The ministry of Jesus was summed up in the words that were sent to John the Baptist when he asked if Jesus was indeed the one that was to come. The answer that was given (Luke 7.22-23) ‘The blind recover their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are made clean, the deaf hear, the dead are being raised to life, the poor are hearing the good news…’ Here the good news (gospel) is about a new vivid encounter with God brought about through Jesus.

I suspect that the Archbishop’s summary of ‘good news of Jesus’ owes very little to the words of Jesus and far more to the use of these words by Paul. We get the flavour of what Paul understands by good news or gospel in the very first words of Romans. Here we see clearly that the good news has nothing to do with the teaching and ministry of Jesus but everything to with what Paul believed about the act of God in the death and resurrection of Jesus, now called Christ. The gospel has, in thirty or so years, changed its meaning from being something that was experienced to something that is an interpretation and understanding of an event in the past. The Gospel, to quote again from chapter 1 of Romans, is the ‘saving power of God for everyone who has faith’. It is beyond this blog post to go much further into Pauline theology to expound this beyond emphasising a second time that there is a marked contrast in understanding what the Good News (gospel) actually means according to Jesus (as understood by the Synoptic writers) and Paul. But what exactly does the Archbishop understand by these words?

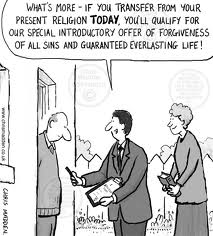

This blog here makes a stab at an interpretation that seems to explain the Archbishop’s use of the words. I have in previous blog posts indicated that modern evangelical theology has a great loyalty to the particular theology of Christ’s death known as ‘substitutionary atonement’. This is a preference for certain ideas that can, no doubt, be read out of various passages in the gospels and epistles. This theology states that Christ’s death in some way ‘satisfies’ God so that he can free humankind from their sin. Once again I am skating over huge areas of biblical and dogmatic theology to make a point in summary. But I want to say that this particular reading of the significance of Christ’s death is one among several in the New Testament. It’s popularity, if that is the right word, among many Protestant and Evangelical theologians, is that it dovetails neatly with another central feature of conservative theology -the theology of conversion. Evangelical theology has always placed a great emphasis on human depravity and sin and the need to escape the ‘wrath’ of God. This preaching emerging from this theology always seems to lead into the creation of a ‘crisis’ where the individual discovers that Christ has taken his/her sins on to the Cross. He offers now a new life, a redeemed life where one can escape everlasting damnation and the threat of hell. The new life always takes place within the setting of a authoritarian institution where the leaders always have the last word as to how this life is to be lived in practice.

In summary the ‘good news of Jesus’ according to the Archbishop seems to be the promise of conversion from sin to salvation by an act of faith in the atoning sacrifice of Christ. Perhaps the one who uses the expression, the ‘good news of Jesus’ with this meaning, needs to explain two further things. The first of these that this ‘good news’ is not what Jesus actually taught or understood by this word. Secondly it needs to be explained to those outside the Evangelical circles, the agnostics and intelligent journalists among others, that the good news of Jesus is far more varied (and exciting) than simply escaping the wrath of God. It is in fact about entering a new life of unimagined richness and depth of experience – the human life shown to us by Jesus.

I don’t think it’s entirely fair to say that all evangelicals who teach that humankind is depraved and invoke the 19th century gothic model of the atonement, are leaders of “authoritarian institutions”. I’ve heard this sort of stuff coming from Anglican pulpits! But I do think that we should all avoid speaking like tracts. You know the old saw about “A lecture is a method of transferring the notes of the lecturer to the notes of the student without passing through the mind of either”? That’s how I feel sometimes about the stuff Christians trot out. (Thinks bubble) “Please, THINK about this stuff”. I haven’t actually come out with this yet. But I did say in a lent course when this was mentioned, “Do you really believe this?” to a Cathedral canon. He was let off the hook by one of the course members saying, “I do”. Pity.

I was basing my characterisation on David Bebbington’s (1989) description of UK evangelicals as those who emphasise the Bible, the cross, conversion and activism. In those words is the pattern I have tried to describe, including the substitutionary understanding of the cross and a fairly conservative view of scripture. The conversion idea nearly always seems to emerge from the context of a Calvinist view of human depravity. I am eternally grateful that this was not my path to faith. While individual evangelicals may choose to differ from this mainstream view, I would have thought that it is the nearest thing we have to an authoritative description of the evangelical movement. Certainly I know of no one else trying to set out such a description of what evangelicals are. An American attempt to do this definition failed as he (Dayton 1991) felt that there were just too many variables.

For me at the end of 2014, the Good news of Jesus includes that death is not the end, that there is a loving God who cares about us, and that it is good to care for others and show them love as much as possible. I also admire hugely the way Jesus stood up for what he believed in, and was prepared to say what needed to be said even thought it cost him his life in the end. I wouldn’t give up being a follower of Jesus for anything.

Have a good 2015!

I just don’t think the weird stuff is confined to the lunatic fringe churches. The person sitting next to you in Saint Gargoyles’ may believe a lot of this stuff, basically because all his teaching has been this. Even if the parish priest doesn’t believe it, this is what he teaches. And I consider myself an evangelical. I’m just nice as well! And intelligent! But I do wonder why I get along better with the Anglo-catholics. According to one of those, it’s the certainty. And I think that’s so. People who consider themselves infallible are a problem, whatever their beliefs.