“From a theological perspective, this fixation with propositions can easily lead to the attempt to use the finite tool of language on an absolute Presence that transcends and embraces all finite reality. Languages are culturally constructed symbol systems that enable humans to communicate by designating one finite reality in distinction from another. The truly infinite God of Christian faith is beyond all our linguistic grasping, as all the great theologians from Irenaeus to Calvin have insisted, and so the struggle to capture God in our finite propositional structures is nothing short of linguistic idolatry.”

This is a quotation that I came across in my perusal of various web-sites that want to support the ideas of a movement called ‘Emergent Christianity’. No doubt my new interest in this US based movement will be reflected in future blog posts, but I was also fascinated by some of the arguments against the ideas of this movement. But when you read a statement, like the one above, that is supporting a set of ideas and you feel you want to cheer, then you feel an automatic attachment to the rest of the ideas that are contained in the movement’s teaching. I do not however propose to conduct a full-scale defence of Emergent Christianity, but to take one single thread of the argument among its ideas, and show that, as far I am concerned, the grounds on which its opponents attack it is fallacious and wrong.

Emergent Christianity contains many strands in its thinking and I do not propose to deal with most of them. However a broad summary would say that it is a movement within evangelical Christianity which seeks to present the ideas and insights of Christianity in a way that allows it to speak to contemporary life, not least the culture and thinking of younger people. The issue our quotation speaks to is the issue of language as a tool for communicating and containing truth. Emergent Christianity has attached itself to the ideas of postmodernism. Once again, risking the dangers of over-simplification, we can say that postmodernism strongly resists the idea that there is a single over-arching version of truth, a meta-narrative to explain or interpret the universe. Truth thus cannot be contained in a single philosophy or theory. To some extent truth is found within the experience of every single individual. This is not the place to defend or attack post-modernism but to note that it has received much negative comment from evangelical writers. They, being attached to the idea that God has revealed himself in the words of Scripture, cannot allow truth to break out from its confinement within these words. The traditional conservative Christian perspective is that faith, truth and doctrine are all expressible through the medium of the God-given words of the Bible. Such an idea can be described as propositionalism, the notion that everything, spiritual or material, can be articulated or defined through words. It is worth commenting, in passing, that propositionalism no longer holds sway in modern physics since there are observed phenomena which sometimes go beyond the scope of ordinary language to explain them. In summary, the conservative Christian wants to claim that truth can always be contained in the medium of words while postmodern ideas of Christianity will want to allow that truth on occasion, breaks out of the straight-jacket of words and is allowed to be discovered in such things as symbols, or visual and musical experiences. The infinite God, to quote our extract above, ‘is beyond all our linguistic grasping’.

It is several months now since I wrote a piece on the contribution of traditional Eastern Orthodoxy to the Christian tradition of today. I have not looked up my precise words on the topic but the kind of thing that I would have written would have been to emphasise the place of ‘mystery’ in Christian belief. The word is based on a root meaning of being silent or struck dumb. Mystery is thus a word that emphasises that words in themselves do not deliver very successfully a sense of the ‘beyond’ in Christian experience. Paul himself speaks of experiences that go beyond words and the mystical writers speak tantalisingly of the unknown in expressions such as ‘divine darkness’. A fourteenth century English writer, who wrote a book called the Cloud of Unknowing, spoke of the fact that God cannot be grasped by the mind but only by love. The Eastern Orthodox to this day fill their worship and their traditions of prayer with a strong sense of the way that God cannot be known, described or even spoken of, except by inference. The so-called ‘apophatic’ tradition, widely discussed in Eastern Christian traditions, declares that God can only be described by saying what he is not, rather than attempting the impossible task of comparing him to created realities in our world.

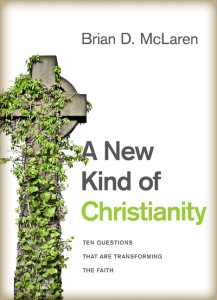

I leave further consideration of Emergent Christianity for another day. I suspect from the tone of the arguments against it, that I shall find myself, if not siding with it, approving of many of the arguments that writers such as Brian Maclaren put forward with great energy. When I hear the argument that truth is only to be expressed in verbal forms, I automatically feel a strong support for whoever is being condemned through the use of such spurious arguments. I am extremely grateful for my education which taught me from the earliest age that truth is to be found in many places beyond words – in beauty, love, longing and silence. I leave the reader with two short quotations from the Psalms where God is approached and known without the use of lots of, or even any, words.

‘Be still and know that I am God.’

‘O worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness.’