Martyn Percy

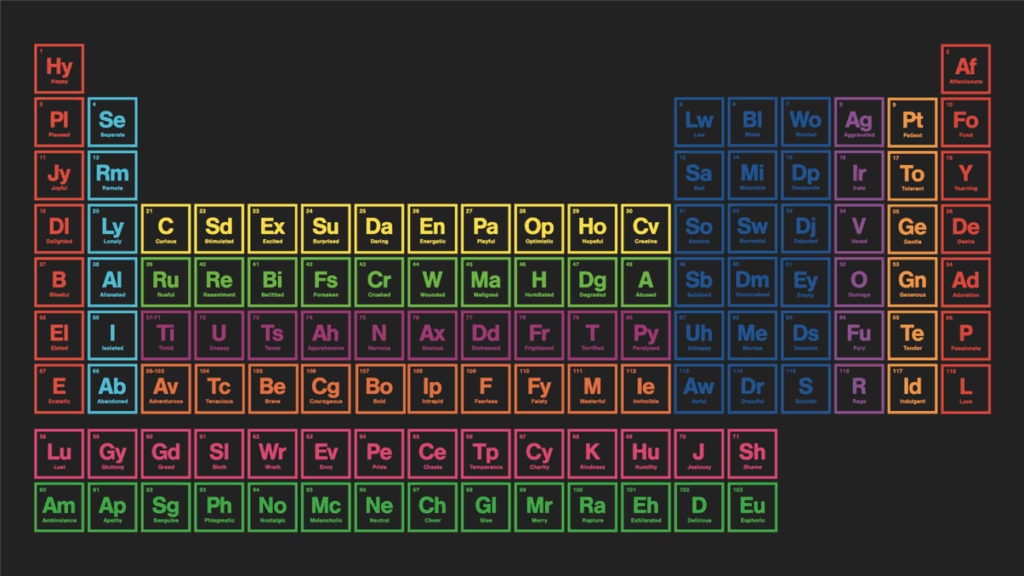

Aidan Moesby’s live art installation, ‘Sagacity’, first appeared in 2015. At first sight, it looks like a periodic table of elements from a school science class. But Moesby’s subsequent print of the live installation is called ‘A Periodic Table of Emotions’.

Moesby’s installation and print replaced hydrogen (H) with happy (Hy). The art goes further: (Bl) is for bleak, (Fu) for fury and so forth. Colours are used to differentiate between the emotions. One group of ‘emotional elements’ is made up of the seven deadly sins. The largest family of emotions is concerned with different kinds of depressive states. These are coloured in blue (naturally), and include sorrowful, dejected, subdued, empty, demoralized, sombre, suicidal, awful, dreadful, unhappy, morose. This is a veritable lexicon of woe. But what of the table above being applied to an institution, organisation, community or nation?

I recall a previous Archbishop of Canterbury describing the national mood of the Church of England and wider Anglicanism as one of ‘low grade depression’. That might have been true then, and for sure, ‘gloomy’ would be a good term to describe how many see the prospects for the national church and wider Communion. True, much time can be spent on blaming others for our moods and emotions. But what might some emotional-ecclesial intelligence offer at this point?

First, there is no real terminology in scripture for the category of ‘emotion’ or ‘mood’. When we do encounter anger, grief and joy, we meet them without reference to our wider framework of emotional wellbeing, which we take for granted today. This might be progress for some, but for others, it turns emotions into pathologies that must be managed, and that is the surest way to intensify those emotions.

Second, as the medieval mystics opined, melancholy was hard to shift, as it was settled state of grief and anguish. I suspect that it is this type of ‘emotion’ that is now gripping the Church of England and wider Communion. The recent announcement of a ‘wellbeing package’ for clergy in the Church of England will only compound that sense of depression.

Third, the collective “pursuit of happiness” (as the 1776 American Declaration of Independence has it) is not a reference to some transitory feeling. But rather to a solid state of liberty where individuals and communities could truly flourish. It follows that if a group or individual cannot pursue this kind of ‘happiness’, anger and resentment quickly surface, with associated emotions of rage and fury.

Emotions, when institutions seek to manage and mute them, quickly witness a downward spiral of emotions for all concerned. That is why Christians have long invested in the notion of caritas – not an emotion, per se, but rather an ‘emotional ethic’. Caritas is a self-regulating spiritual exercise of the will, heart, and mind – to foster and offer compassion, empathy, alms and abundant love and care beyond the usual bounded constraints of personal desire.

Caritas is what we expect from our parents, hope from our partners, and will be grateful to receive from our children. Caritas is what those with less hope, pray and yearn for. It is what those who have more must engage with in their ‘soul work’. The irony of caritas is that when we learn to give and receive it, which is a duty, we quickly encounter joy.[*]

This is perhaps the most acute problem for today’s English Anglican leadership. It appears to have lost its emotional intelligence; sorely divorced from and devoid of caritas. Announcing a new ‘well-being package’ for clergy addresses some material concerns that have impacted ministers, as the Church of England recently did.[†] But it does almost nothing to assuage the sense that this is an organisation that responds to serious emotional need, depression and trauma with a ‘wellbeing package’, as was the case recently. The choice of language and the initiative are more likely to compound the sense of alienation many now feel.

Furthermore, clergy themselves feel processed, managed, and muted, as they have never done before. For example, clergy seeking to conduct marriages or take funerals outside their diocese, or from another province, will frequently encounter elephantine processes that treat the clergyperson as a potential risk to be managed, the event as a potential hazard that also needs vetting and risk management, and probably additional training, forms to be filled in and more besides. This robs clergy of their agency and role. It trespasses on the broad and deep range of emotions a minister might try to manage at a wedding, blessing of a couple, burial or cremation.

To add insult to injury, the persons presuming to undertake the vetting process and risk management on behalf of a diocese or bishop have no external accountability to any independent professional body, and there will be no appeal against decisions taken, or how any request is dealt with. There is nowhere and nobody to complain to (other than internally). This anti-caritas compact feeds distrust and fosters the range of depressive emotions cited above.

The only way out of this is for the leadership of the Church of England to recover its heart and soul, and rediscover caritas for leaders who preside over ministry. Political compromises on divisive moral debates will not resolve the raw underlying feelings of shame, anger, melancholy, grief and fathomless sadness that the concerns prompt, simply by appearing as an item on some agenda as an ‘issue’. Nor will more managerialism – packages, visions, strategies, initiatives and the like – compensate for the sense many have on the ground in parishes.

That sense is this. They might not matter that much; they represent a cost to an institution that it can no longer afford; they must be treated as a potential risk and accordingly managed; they are an agenda item, and so are their issues; and they might just be one more problem or issue that can hopefully wait, or solved with minimal intervention (i.e., contactless – though there might be an email or letter). The sense that the clergy have is that they are just units to be ‘processed’ in a system, and that their grief over their wellbeing can be assuaged by some new ‘package’. The ‘package’ will be announced with much fanfare and enthusiasm. It will be met with ennui.

Without caritas, the church is as doomed as a family without love. The Church of England leadership now stands at a testing existential crossroads. Shepherds or Managers? Pastors or CEOs? How the church treats its own will be replicated in how wider communities and parishes feel the church is treating them. The current ecclesial crisis is an emotional-existential matter, requiring solemn reflection and sober, sincere, serious repentance.

If we look forward, the emotional terrain looks set to get tougher. The views of Charles III’s son and heir, William, are thought to be somewhat tepid on the matter of the Church of England. The future William V could signal to the government that the reigning monarch, acting as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, might have been a valuable arrangement for national interests in 1534. But it is very hard to make the case for this in 2034. The sense of dislocation is thick in the air but denied by the leadership. It is as though the bishops think Jesus himself said, “keep calm and carry on” – no matter what the reality is.

England is hardly beholden to its national church anymore, and a litany of safeguarding scandals, cover-ups, managerial failures and general indolence has left the broader population disenchanted with the current leadership. The likelihood of that being reversed seems slight, and the Church of England seems set to become an increasingly marginal element in the day-to-day lives of its citizens, if baptism, confirmation, wedding and funeral statistics are anything to go by. To say nothing of the bleak news on usual Sunday attendance (uSa).

Meanwhile, across global Anglicanism, our churches worldwide can now barely relate to one another, given that the divisions on issues of sexuality, polity, order and the like are so deep, bitter and profound. Most other Protestant denominations have entered into bespoke semi-detached modes of separation. Still technically married and bearing the same family name, but not living together and leading separate lives, is perhaps the best analogy? Or, same grand house, shared hallway, but otherwise divided into flats with separate entrances. Some neighbours talk to each other. Others do not.

That might work for a while, but there comes a point when money, property, assets and savings need to be shared out, and the running costs divided up equitably. Lawyers tend to get involved at this point. This is why emotional-ecclesial intelligence needs to be recovered. What can Anglicanism do, going forward? There are three possible options.

First, there is the carry-on-disagreeing option, though this has had its day, and too much ink (and maybe blood) will be spilt with hoping against hope that schism can be avoided. All the signs in this option point to implosion and weary resignation. The price of this option – full Communion – is one that few will invest in, and many have already turned their back on it.

Then there is the second option that suggests you divide from those you no longer agree with, and/or expel the heretics. Some conservative proponents champion this course, but it’s unlikely to gain much ground because, while hot on specific moral issues, conservatives can be a bit slack on canon law, and do not mind, for example, lay people celebrating holy communion. If moral deviancy is to be punished, what about liturgical or canonical defiance?

Then, there is a third way. It must be accepted that the worldwide Anglican Communion is really a construction of the British Empire, though it has eventually evolved into a more equitable commonwealth – or better still, a worked-out federation. Anglicanism is undoubtedly global but is now too diverse to be centrally or collegially governed in a manner that guarantees unequivocal unity. Its future lies in adopting federalism, and not trying to copy ‘Communion’ catholic-speak.

Option one is poisonous, and option two would be a lawyer’s dream ticket. But option three can be worked out through love and caritas. In the meantime, call nobody ‘Raca’ (Matthew 5: 22). For that matter, be careful about lazy labels like ‘liberal, ‘conservative’, ‘traditionalist’, ‘progressive’ and the like. Such labels rarely work well. Just look at the nomenclature of ‘Anglicanism’.

In God’s eyes, we are all fools and blind to the spirit of the age. Instead, settling our differences in a spirit of love, equality and justice might be wise and prudent. Anglicanism need not be afraid of divorce or separation because, if done well, it can bring peace and sponsor new kinds of love and respect. However, this requires a level of emotionally intelligent leadership and ecclesiology, which is currently lacking in Anglican polity. Grief is the price we pay for love; we must all let go eventually. And let go, we will. In the meantime, treat others as you would want to be treated. God will judge us all with piercing truth and justice. God has contempt for no one. Only love.

[*] Amongst the best writers on the history of emotions is Katie Barclay. See her The History of Emotions: A Student Guide to Methods and Sources, London: Bloomsbury/Red Globe Press, 2020. See also Thomas Dixon, The History of Emotions: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: OUP, 2023 and Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears, Oxford: OUP, 2015.

[†] https://www.churchofengland.org/resources/clergy-resources/clergy-wellbeing-package

The Church of England doesn’t appear to have a mechanism for change. I’ve been saying this for years now, and always want to be wrong.

However it does have mechanisms for stasis. Nothing must change. Inertia rules.

The only factor having a significant mutative impact is money, or rather the lack of it. The dynamics of the various schisms usually seem to have money matters lurking murkily in the background. For example the ongoing HTB-isation reflects theoretical pecuniary gains from its various initiatives. Whether this is true church growth or an exercise in self entertainment for the aspiring middle (hoping to be upper) class masses, is debatable. Central command and control isn’t squeamish about what goes on, so long as the cash rolls in. But overall the funds are draining out.

As long as the closeted few are comfortable in their palaces, nothing will change. Why should it? There’s plenty enough yet to keep them comfy well beyond their lifespans. Obviously jobbing clerics on pants wages can be sacrificed at will, particularly when there are plenty of non-stipendaries willing to work for nowt.

I seem to struggle to think of a clergy person who isn’t depressed at least some of the time. And collectively, the melancholy perhaps reflects a deep anger turned inward at dreams lost. With no one seeming to be in charge, no wonder the tendency is to blame the self.

“Necessity is the mother of invention” and the dire crises within Anglicanism could see much needed changes bring improvement. The Leicester Diocese case, with Venessa Pinto-Jay Hulme-Bishop Martyn Snow, exemplifies so much of what is wrong with tragic failure to routinely protect adults.

Posh boarding schools have a lot to answer for. What used to be called the working classes are often more emotionally literate, though they may be less articulate in expressing it.

Couldn’t agree more. A professional class that believes in nothing but their own self entitlement, personal aggrandizement, has had compassion and mercy beaten out of them, that lives in a world very different from the majority of us, that can fail and cock up.and even maliciously act without any accountability running the country and many other institutions. I mean, what could go wrong??!

Perhaps if our whole system was more democratic and not top heavy with posh wealthy public schoolboys who had the ‘bejeesus’ beaten out of them, we might actually have something resembling a nation and equitable society and not a closed shop or privileged gentlemen’s club run like a posh mafia in effect.

I’ve been reading through this well written and excellent blog for a while. For what it’s worth, and for the record I am just an ordinary practising Christian from a working class background, I have never been a big fan of the CofE or mainstream hierarchical religion for several reasons.

‘To add insult to injury, the persons presuming to undertake the vetting process and risk management on behalf of a diocese or bishop have no external accountability to any independent professional body, and there will be no appeal against decisions taken, or how any request is dealt with. There is nowhere and nobody to complain to..’

Here, as with all hierarchies, is the gold plated problem. Accountability. Powerful and influential people of any kind really really do not like any kind of accountability do they? They despise it. It seems we the plebs cannot hold our overlords, the tin gods many of them think they are, to any kind of account in any way. They all do what they want on personal and public levels that often cannot be questioned. Criticise the royals in any way and you will see this particularly writ large.

Now, I believe that nobody is above the law. But in many senses I believe we have gone back to a kind of unspoken Mediaeval attitude, which is along the lines of the powerful do and we must know our place. It’s never expressed but the way powerful organisations, governments, institutions and establishments act and treat the rest of us speaks volumes.

The old English Civil War argument was between ‘the king is the law vs the king upholds the law’. I am not a dyed in the wool scholar in these matters but smart enough and educated enough to see that we have regressed politically, socially and economically. The CofE being really an arm of the establishment is just following suit. Powerful people justifying their power and wealth and post imperial business, politics and various geopolitical and global ambitions and adventures. But what’s new?

And what of morality, and indeed what of Jesus? Do the leaders of a mainstream church represent Christ or the British state? I have already made my decision on this question.