UCCF again – some recent developments

Back in 2015, in the early days of the blog, I wrote a piece https://survivingchurch.org/2015/09/19/christian-unions-at-university-an-account/ which used a firsthand account of what a student reported about her experiences of membership of a Christin union at university. The writer of the letter, Kirsty, had googled the words ‘damage caused by Christian union involvement.’ Google had thrown up an article of mine written on Surviving Church about CUs. Apparently, this was, at that time, the only discussion on the topic easily available. From what Kirsty had to report there was a clear need to discuss the topic even if the internet generally had little to offer on the issue. Kirsty wrote of the ‘emotional and psychological residue’ that she was still trying to process fifteen years after her time at university. She also spoke of ‘mixed feelings of sadness, pain and guilt around my involvement with this strand of Christianity.’ Alongside Kirsty’s description, which she graciously allowed me to reproduce in full, was my reply. I confessed to her that the wider church beyond Christian unions and the conservative Christianity taught there often showed little understanding of the problems faced by those who, for whatever reason, fell out of sympathy with Christian union teaching. I mentioned a particular issue with some conservative ideas about sin. These could easily undermine self-esteem and the ability to love oneself.

Looking back on my online conversation with Kirsty, I realise that what she was describing in 2015 is an issue that has never gone away. Students at university are encountering the presentation of a religious message which, while it seems to liberate some, throws others into a form of depressive bondage. From my liberal-catholic background, I share the belief that Jesus came to bring Good News, but I have never linked this gospel with a need to fight off constant feelings of gloom and despair. One writer described the depressive state associated with some presentations of the Good News as an ‘evangelical anorexia nervosa’. My own theological perspective has given me access to a journey of finding constant newness and adventure. Over 2000 years, different cultures and races have thrown up an enormous range of Christian ideas in their attempt to make sense of Jesus Christ and his teaching. For me there has never been a single unchanging version of the Good News. The Christian faith and the good news contained in it comes in many guises and expressions. We only need to have the barest appreciation of human language to know that every religious thought or belief is subtly varied according to the language and culture in which it is articulated.

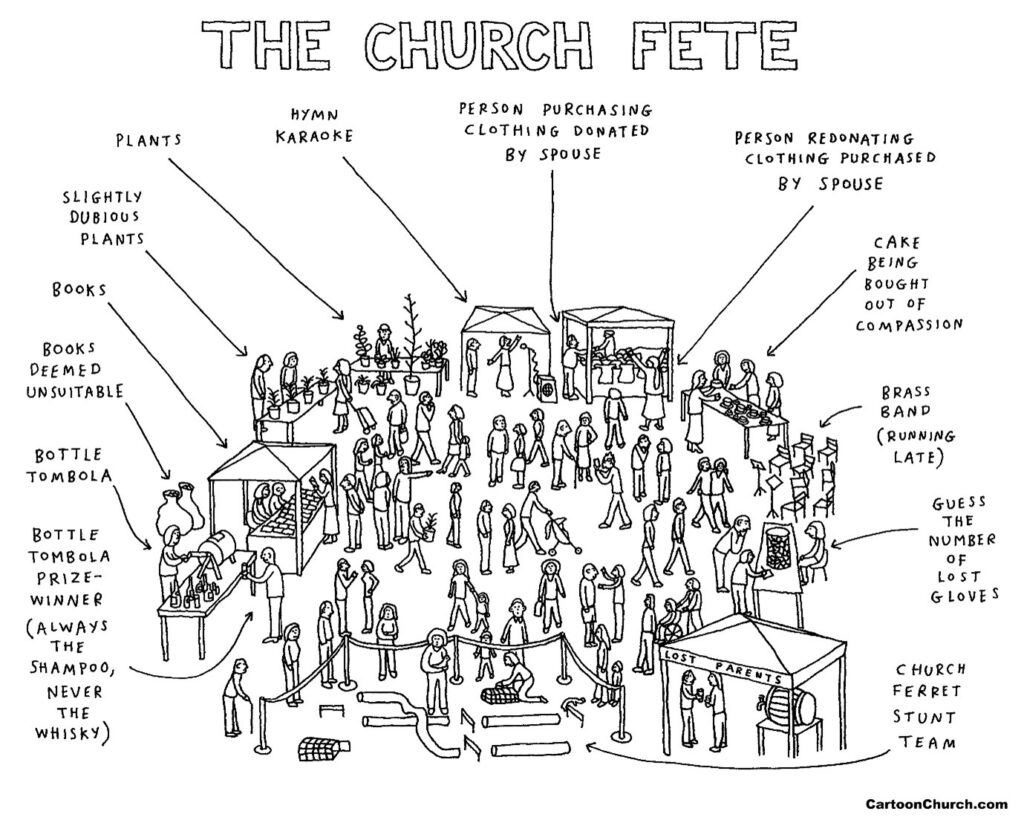

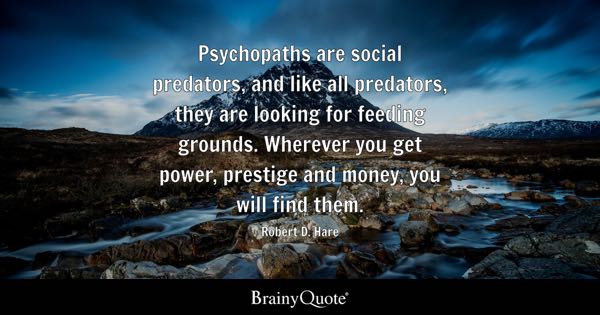

The Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship (UCCF) has, over many decades, had a dominant role in the sharing of the Christian faith to students across Britain. The expression of the faith that is articulated by this organisation is, as we have seen in the October 23 blog and the online conversation with Kirsty in 2015, a strongly conservative message. UCCF is ‘successful’ in one notable way, in making its brand of Christianity far more prominent than any other. No other organisation comes close to recruiting and supporting the dozens of young people who promote and organise the work of Christians unions in almost every centre of higher education in Britain. The work has been going on over decades and, speaking generally, UCCF is responsible for much of the conservative evangelical culture found in many Church of England parishes. UCCF does all this work independently and it is not under the control of any external denominational structure. It has thus created its own distinctive way of doing things and it has done this without attracting attention to itself. Nevertheless, new episodes have disturbed the calm at UCCF over the past few months. The first episode which we looked at in October was the suspension of two of the senior directors, Richard Cunningham and Tim Rudge, in December 2022. The suspensions resulted in a report being made by a KC and this was received by the Trustees in June 2023. The event was marked by a number of apologies to the workers who had raised complaints, apparently about employment conditions. Both directors were subsequently permitted to return to their posts. We commented in the October blog on the way that whole episode had been marked by secrecy. While we suspect that the problems at the organisation were to do with the non-observance of aspects of employment law, no explanation for the suspensions and reinstatements have ever been given. There were, however, clear signs of unhappiness at the national headquarters of the organisation. Over a fairly short period, half the trustees have resigned, including the chairman, Chris Wilmott.

Since October, three new events have emerged which add to the drama that surrounds this currently beleaguered organisation. In February this year, a former worker and team leader, Nay Dawson, published an account of her part in creating the ‘unhealthy’ culture which ‘damaged’ employees. Her words seem to have been inspired by the issue at the heart of the organisation – the conditions of employment for junior UCCF workers. These have required the young employees to work under terms which appeared to be neither legal nor ethical. The UCCF employment conditions expected all the young people who were salaried to work for a fixed period, three or five years. They were then expected to resign to make way for a new group of recent students. Employment law makes it clear that anyone who completes a probationary period in a job satisfactorily cannot simply be pushed aside to suit the needs of the organisation. Nay realised that some of those under her who were being required to resign, were experiencing considerable distress at the inevitability of their departure. She began to see that, in her role as team leader, she had been required to be part of this cruel enforcing process. Her article which articulated her own pain and sense of regret was widely read and it created quite a stir on X/Twitter. The article was exposing the secretive world of UCCF to open criticism which it would clearly wish to avoid.

If I had personally wanted to move on after my October 23 blog, the twitterverse, or whatever it is called today, made sure I was fully aware of everything going on in the past few months at UCCF. Because my article was attached to many of the X discussions, my inbox was full of UCCF online chatter which was following this drama. Almost all of it was critical of those in charge at UCCF. Two further events followed Nay’s article. This was publicised in Premier News. Premier also reprinted a confidential internal UCCF document from 2009. This set out the issues about UK employment law and how these could be made to fit with the actual practice at UCCF of requiring employees to move on after three or five years. The message of the document had a hard edge to it and no concession was given to employees who might wish to extend their period of employment with UCCF. Clearly the resignation of half the trustees was probably linked to the internal differences which Nay’s article was articulating, but nothing seems to have changed and certainly nothing has been made public. Meanwhile one of the reinstated directors, Richard Cunningham, has resigned from his post and we are left to speculate the real reasons for his departure.

Nay’s article in the Premier magazine has been followed up by another letter from one Katie Norouzi. This appeared on the 11th March and supported all that Nay had said about the effect of her experiences of employment with UCCF as a staff worker. Katie was called to an interview/appraisal with a senior member of staff which she felt was set up, even designed as a means to deliberately undermine and humiliate her. The encounter seemed designed to crush her in such a way that Katie would feel compelled to resign. In Katie’s words, she asked herself ‘did I have fundamental weaknesses that meant that I couldn’t do the job? Was I failing to serve Jesus well in the role he had given me?’

Katie’s story, which tells of the way that an organisation puts its own interests ahead of the people it was supposed to serve, reminds us of the CofE and its repeated failures in safeguarding. UCCF has been able, for many decades, to avoid giving an account of itself to outsiders and also to those who work for it. That may be about to change. The events that have taken place since the suspension of the directors in December 2023 have created a situation which necessitates it bringing new blood into the organisation. Those coming as a new Director or as trustees will each need to be briefed on what has taken place over the past 15 months. They are unlikely to agree to serve in an organisation that has skirted illegality and maybe even colluded with financial misconduct. Some hints of financial impropriety in the organisation have also leaked out. No new official would want to be part of an organisation that may soon face scrutiny from the Charity Commission. Change is in the air at UCCF. Their achievements over the past hundred years are remarkable and important. Even if I have little sympathy for the theological vision that undergirds their efforts, it does not stop me having respect for the work that has been accomplished. Perhaps a new start the top will create a new healthy spiritual and open environment for UCCF. The respect of outside Christian bodies is important and that will not be obtained unless UCCF makes a clear ethical response to the crises that the organisation has faced over the past months.