One of the features of becoming an incumbent in the Church of England is the fact that you have to become knowledgeable in a variety of areas that were, in my day, barely mentioned at theological college. The world of finance, money raising, legal protocols and the preservation of ancient buildings are not areas of knowledge where clergy have much instruction or can claim any special expertise. This is particularly true if, like me, they have not been in the world of work before ordination. If a vicar is fortunate, he/she will find competent lay people to assist in such tasks. Having sound reliable lay officers in a parish situation is an enormous bonus, but it cannot always be taken for granted. If we were to complain that the average vicar is forced to accept responsibility for areas where he/she can claim no special skill, the problem gets more pronounced as you go up the hierarchy. I spoke in a recent blog piece about the importance of a vicar getting on well with volunteers that work in a parish church. There might be up to twenty such individuals working in a medium size congregation. When you consider a cathedral, the number of volunteers at work may be in the hundreds. In an organisation like a cathedral, if smooth functioning is to be achieved, considerable personnel/management skills are required of those in charge.

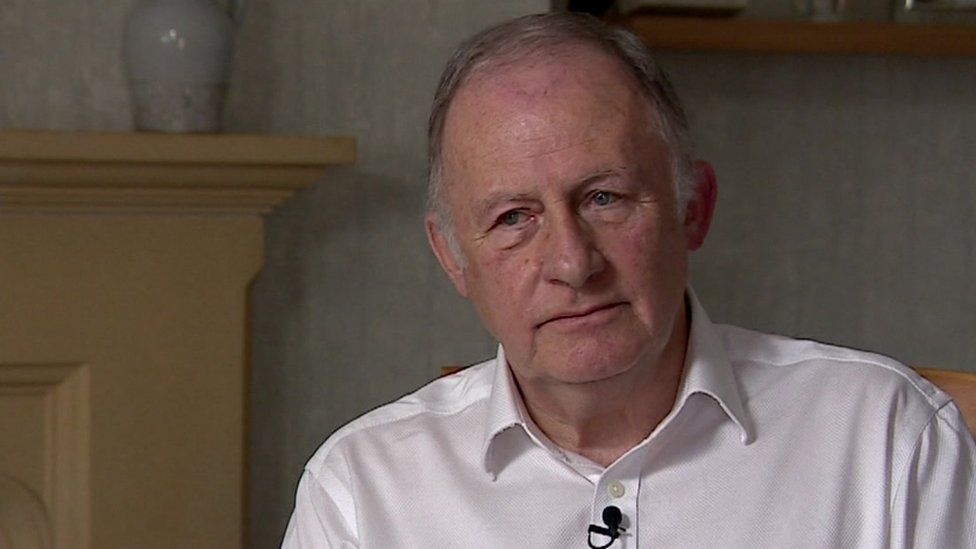

The administrative tasks of very senior clergy in the Church of England are, in comparison to ordinary vicars, enormously demanding. A glimpse of the full range of skills needed for a senior bishop, such as the Bishop of London, was revealed to me in some detail when I read Bishop Chartres’ Lambeth Lecture for 2015. Obviously, part of the skill of successful management involved delegating many tasks and responsibilities to other clergy and lay officers. The really important decisions still fell to the Bishop himself and many were to do with strategy and buildings. We read, in the lecture, of the decisions that had to be made over redundant church buildings and vicarages. The financial implications of holding on to a church building in a state of disrepair were potentially crippling. Equally, releasing a piece of potentially valuable real estate in a city like London for less than its market value would also damage the church financially. The Bishop needed help in these kinds of matters. The nitty gritty of sorting out property deals and seeing the potential of buildings was not one to be placed on a bishop’s shoulders. Like a vicar having to deal with an area of administration for which he had no previous experience, Bishop Chartres looked for help. In his own words, he said ‘Part of the answer was a partnership with a remarkable layman, Martin Sargeant, who had an eye for development possibilities and enjoyed considerable respect from the City Corporation and developers alike. His negotiating skills and attention to detail were also crucial in turning ideas into profitable ventures where both the Diocese and a range of Christian-based enterprises were benefited’.

Sargeant began working for Bishop Chartres in 1997. At first he was used as a go-to consultant for property matters, but his place in the Diocese was made official in 2009 when he acquired the title of Head of Operations. It appears now, according to the recently published Review by Chris Robson on the Fr Griffin affair, that Sargeant, in fact, had no defined place within the formal structures of the diocese. The reviewer could not find any contract or conditions of employment. Even the sources of finance from which his salary had been paid were wrapped up in mystery. It seems that Bishop Chartres had become dependent on Sargent for his range of skills in such a way that the protocols of due diligence were cast aside when the full-time appointment as Head of Operations was created for him. To bring this story right up to date, Sargeant, on the 8th July, has been charged in connection with a fraud case involving a missing £5 million. Some of this money belongs to parishes in the Diocese of London. Even if Sargeant is still allowed the presumption of innocence until proved guilty, it is hard to see how so much money could vanish without him having some knowledge of what had happened to it. Clearly, we recognise now that, at the very least, the former Bishop’s trust in his property/financial ‘fixer’ had been grossly misplaced.

The now ex Head of Operations in the Diocese of London also plays a prominent part in another tale of London diocesan woes. Although he is not named, Sargeant is an important figure in the story uncovered by Hobson’s 49-page lessons learned review of the Fr. Griffin affair. The infamous ‘brain dump’ that took place during 2019 between Sargeant and the Archdeacon of London and others, was the start of the disastrous series of events leading to Fr Griffin’s suicide in November 2020. Sargeant wanted to share information that he had picked up in the course of his work in the Diocese over twenty years. This included personal information about the clergy, including Fr Griffin. Some of this information was factual but much was salacious gossip. The details of what went wrong and the way that mishandling of sensitive information was to have so serious an effect on the state of mind of a priest, is set out in Hobson’s review. The point that I wish to focus on here is when the reviewer queries the Archdeacon’s competency in safeguarding matters. The answer he gives is that the Archdeacon was a ‘generalist’ in these matters. At a second meeting with Sargeant, the Archdeacon was accompanied by the Head of Safeguarding who was also the Human Resources lead. Once again, the reviewer questions whether there was in the room sufficient expertise in safeguarding matters to recognise the implications of receiving material of this kind. Nine hours of testimony from Sargeant was received and this was in the end written up to form the Two Cities Report. The process of scrutinising all the information by safeguarding professionals in both the Anglican and Catholic churches was eventually achieved, but the whole process took an inordinately long time. Trust between the clergy mentioned in this report and the current Bishop of London has been seriously damaged by the ill-coordinated management of this material.

The theme of this blog piece has turned out not to be about the safeguarding failures in the London diocese that contributed to Fr Griffin’s death. It is rather about the difficulties experienced by senior church figures in coping with areas of institutional complexity which go beyond their experience and competence. Bishop Chartres seems to have been an enormously able and respected bishop of London, presiding over the only diocese in England to record a growth in numbers in recent years. This apparent super-competency, however, had its limits. He put his personal trust in a property/financial ‘expert’ and the consequences of that trust seem to have been disastrous for the diocese, both reputationally and financially. The fact that the selection seems to have been informal and outside the normal protocols of recruitment, made it his personal choice. This also hints at the possibility that Chartres was well aware of the controversial nature of the appointment and that an open system might not have approved this hiring of someone apparently answerable to him alone.

In the second case we have the Archdeacon of London possessing, according to Hobson’s review, ‘generalist’ skills but being expected to deal with a mass of ‘dumped’ information, giving rise to potentially huge safeguarding and pastoral issues. Going into that meeting with Sargeant, without any clear idea of how he was going to deal with the promised information, was fateful. A clear-eyed response to the sequence of events at this point would be to say that that the Archdeacon quickly got out of his depth and was too slow to reach out to others for the right help and advice.

The recording of two serious errors of judgment by senior members of the London diocese which led to unforeseen but catastrophic consequences, is not meant to be a suggestion that either man is guilty of some deliberate wrongdoing. Both, no doubt, believed at the time they were acting according to the best information available. The real problem was that in each case the skills and expertise for making a correct decision were insufficient. The Church has to take some responsibility for not resourcing its leaders better for these kinds of situations. Property management should never depend on a bishop’s hunch about the (dis)honesty of an individual. There have to be better and more reliable means of managing property and other administrative affairs in a diocese. Ultimately the church would be a healthier place if individuals were better at being aware of the limitations of their skills. At present we place far too many clergy and others in places where they have to make decisions which are sometimes beyond the skills they possess. Is it right that all clergy, from the Archbishop of Canterbury downwards, have to take responsibility for so many complex decisions, whether over finance or safeguarding? Would we not prefer it if our bishops sometimes admitted that they did not know the answers to questions put to them? Do we really want them to depend on their finite abilities or go running off to take legal advice every time someone challenges their authority? We have to admit that, as much as we would like bishops in the CofE to take charge of so many policy issues In their dioceses, it is sometimes demanding of them skills and expertise which many of them simply do not have! An extra beatitude should be added to those that already exist. Blessed are they who know their limitations!