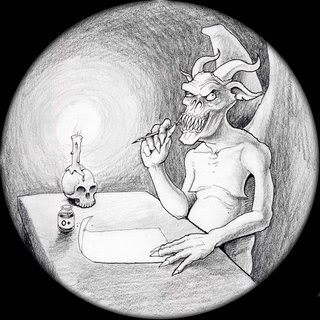

Damon is an apprentice devil tasked with learning to undermine and weaken the Church of England and wider Anglicanism. Lucius is a senior devil mentoring apprentices overseeing the work on all denominations. Lucius refers to the Church of England as the ‘English Patient’. Lucius is particularly keen to encourage the Church of England’s peculiar ecclesionomics, bloated ecclesiocracy and unaccountable episcocrats. Lucius draws on C. S. Lewis’ Screwtape Letters, published in 1942. These letters are published by Lucius for the benefit of new apprentices. – Lucius.

Safeguarding the Church

Dear Lucius

After much success on the safeguarding front, there are signs of a fightback from the ecclesiocrats. They have recently advertised for some new Head Honcho who will apparently take the English Patient a few more steps towards independent scrutiny. We of course already know that this is another PR-trot around the Lambeth Palace paddock, and it will be business as usual, so I am not worried by the disingenuous policy announcements and spin that comes from the Archbishops’ Council. Had we recruited some crack team of double agents, we could have hardly done better.

No, what worries me is the appearance of action on safeguarding, and the possibility of the average worshipper being duped. I find myself in a double-bind here. It is meant to be us misleading the faithful, not stopping the Church of England hierarchy doing this to their own people. True, we are about slightly different things here. The hierarchy of the English Patient is trying to present a positive gloss on areas like safeguarding, and create the (false) impression of progress and the appearance of things improving. We know that is a lie, of course. So does the hierarchy of the English Patient.

So you can appreciate my dilemma here. Do I expose the lies? Or do try and come up with other falsities which add to overall strategy of misleading churchgoers? I’d be grateful for some help on this one, because deception is such a delicate art, and to be honest, I find the hierarchy of the Church of England to be really rather good at this game, and that is slightly irksome to say the least. Any advice?

Your Servant, Damon

Dear Damon

I rather agree that this is perplexing, and the issues you describe would usually be tackled in the post-apprentice training. But as you have the cure of souls for the English Patient in your own right, it only seems proper that I offer some counsel for your edification and encouragement. Happily, a new safeguarding charter by the Church of England was sent to me the other day. It turns out to be a perfect recipe for the further destruction and implosion of congregations.

In fact, it is a veritable gold mine of undeliverable and incoherent policies, and once people try to follow the rubrics, they’ll quickly realize there is little point in going to church at all. So, here are three nuggets from the document.

First, anyone working with children and vulnerable adults has to be checked, processed and regulated. Helpfully from our point of view, a ‘’vulnerable adult’’ is on the one hand someone unable to look after themselves. But more helpfully, it also includes anyone who seeks support from the church, either temporarily or permanently. So anyone with any needs at all that the church might help with is ‘’potentially vulnerable’’. Which means anyone trying to help or support anyone at all, pastorally, spiritually or otherwise, falls in the category of needing authorization, vetting, approval and regulating.

Second, the new regulations make it clear that anyone who does anything in church that has an interface with anyone else (who, let us not forget, could be ‘’potentially vulnerable’’) means they need regulating too. Under the old regulations it was just licensed ministers, the choir master, Sunday School leaders and maybe the layperson who preached the odd sermon. Now, the new regulations say that anyone who has contact with a child or ‘’potentially vulnerable adult’’ must be vetted and approved. So that covers anyone involved in visual, verbal or written communication, or exercising any power or influence in church. Basically, that means almost everyone who goes to church.

Third, and you really cannot make up this good news, there is a sort of ‘’get out clause’’. If you are one of the helpers doing the post-church refreshments and someone approached you who was upset, you can only talk to them by making it clear that you cannot help at all, and then you must direct them to the designated person who is vetted and approved. This is great, because in the meaning of the counsel offered, churchgoers will get into trouble if they attempt to help any child or ‘’potentially vulnerable adult’’ unless they have been licensed to do so, been trained, scrutinized and are now regulated.

All of the above has been passed through the ecclesiastical lawyers – arguably our greatest allies, along with the bishops and ecclesiocrats – and clergy and congregations are threatened with dire legal consequences if they default on the counsel. Naturally, clergy who might feel that they have just become ‘’potentially vulnerable adults’’ after they read the new regulations will be petrified when they learn that they carry all the responsibility for implementing this, but have no power to order around their laity and volunteers.

The conclusion that believers would draw from the document is that they must not get involved in helping others unless they have been vetted and licensed. And if they haven’t got the appropriate training and fulfilled the regulatory requirements, they must decline to help and find somebody who fulfils the criteria the ecclesiocrats have laid out. Most people reading the document would conclude that church is an unsafe space to be, brimming with serious risks and potential hazards, but that if they were to try and respond to anyone in need, they might expose themselves and the English Patient to further risk. So, it is best to stay at home. If you do happen to go to church, make sure you don’t talk to anyone who needs help of any kind. Anyone, really.

To be honest, Damon, safeguarding is the gift that keeps on giving to us. And here we have not so much struck gold as found the most humungous gold mine that defied my wildest expectations. Once worshippers realize what these new regulations actually mean, they’ll stop going to church, and tune into Sunday Worship on the BBC, or play some old Harry Secombe religious vinyl records.

I know it is a bit naughty of me to confess this, but even I had a soft spot for his Welsh baritone voice singing gospel hymns. It’s funny how we learn to admire and respect the opposition after we have been fighting them for so long. And we really thought we could turn Harry Secombe to the Dark Side after some episodes of the Goon Show, but it turns out that he had a stubborn religious streak. Well, I suppose we can’t convert everyone.

Then again, we may not need to. These new safeguarding regulations are an entire pack of nails in the proverbial coffin of the English Patient. It makes the whole business of going to church almost impossible, and subjects every service and church event to a multi-faceted risk-register that must be managed – on pain of death. I find myself almost feeling sorry for churchgoers and clergy. But then I remind myself of our purpose. And then I come to my senses, and realize how blessed we are with such a clueless English Patient.

So, don’t worry about these new initiatives in safeguarding. This is another example of the English Patient pressing the self-destruct button. We hardly need to give them a helping hand at all here, save perhaps to encourage the ecclesiocrats in their bid to take over all responsibility for ministry, monitor the clergy, vet the laity, police the worship and all church events, and otherwise regulate congregations out of existence. And all in the name of safeguarding!

I just think it is wickedly funny how diabolical and dangerous safeguarding in the Church of England has now become. So, let your English Patient continue. This is another episode of ‘’Carry on Regardless’’, with extra farce and slapstick. To be honest, this is all heading in the right direction from our perspective.

Your Mentor, Lucius