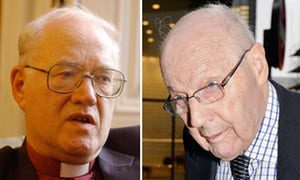

Next week the Church of England is going to have to endure yet another scrutiny at the hands of the Independent Inquiry and the press. The issue at its heart is the criminal sexual abuse by a bishop of a group of young men who believed that they were following a path set out by God. The facts of the case have been thoroughly rehearsed in a court of law so that in many ways the details of Peter Ball’s abusive behaviour do not need to be further discussed. Damage has been done, severe damage, to the lives of those affected but we are left with a need to understand some of the implications for the wider church community. It is these that I want to reflect on in this post. Above all I see the Ball case as a study of the dysfunctions of power in the church. The lessons we can learn from it are relevant today.

Next week the Church of England is going to have to endure yet another scrutiny at the hands of the Independent Inquiry and the press. The issue at its heart is the criminal sexual abuse by a bishop of a group of young men who believed that they were following a path set out by God. The facts of the case have been thoroughly rehearsed in a court of law so that in many ways the details of Peter Ball’s abusive behaviour do not need to be further discussed. Damage has been done, severe damage, to the lives of those affected but we are left with a need to understand some of the implications for the wider church community. It is these that I want to reflect on in this post. Above all I see the Ball case as a study of the dysfunctions of power in the church. The lessons we can learn from it are relevant today.

In looking back over the sad case of Peter Ball, we can first reflect on the nature of the power that he personally exercised. As a bishop in the Church of England, he had considerable social power. Social power was enhanced by his going to the right school and university. His social standing and his status as a bishop meant that he was automatically put in a position of trust by everyone who met him. Nobody needed to make a judgement about his personal honesty or character. The Church in its wisdom had selected him as a priest and a bishop. Throughout his long priestly career of service to the Church those in authority had, it might be assumed, watched over his behaviour and conduct. As a bishop, Ball was welcomed into places right across the social spectrum, the homes of ordinary people as well as the dwellings of the highest and the grandest in the land. Episcopal status and social confidence created a standing which was difficult ever to challenge or question.

Social power was not the only kind that Ball possessed. There was an additional power which is common among some bishops and church leaders. This power we can describe as charismatic power. In using this word, I am not hinting at a churchmanship which involves speaking in tongues or gifts of the spirit. I am speaking of charisma in its wider meaning. Ball had charisma and an ability to inspire, charm and encourage others. His presence in any room or gathering was likely to be the dominant one. We sometimes speak about some personalities being larger than life. Ball was one such and no one who met him failed to be affected by the energy of his personality.

Charismatic power in an individual, as we recognise increasingly today, is a double-edged sword. It can be used to build up others; equally it can be deployed to manipulate others when required. Charismatic power and social power when operating together make an individual very difficult to resist. But, in addition to these forms of power, we must add a third, which is institutional power. People naturally defer to those who are in charge within an institution not least because they have the power of patronage. It does not pay to stand up to anyone in a firm who can make or break your career within the institution. Ball, as a bishop in the Church of England, would always have exercised considerable power in the church even before we add the additional social and charismatic strengths which he possessed. The three sources of power that he had, allowed him to float above suspicion or challenge for decades. If there were concerns at any point about his behaviour towards young men, he had the means to quash such rumours or innuendoes fairly quickly.

Next week we are going to hear once more the sad story of how the Church of England was defeated in its attempt to rein in Ball’s power over decades. Reading the Gibb report once more, it is obvious that Ball was adept at manipulating others even after the English justice system had extracted from him a serious admission of guilt in 1993. The simple way to interpret the events that took place in the years between 1992 and 2015, when he was sent to prison, is to see them as a conflict of power systems within the Church. As I read it, the events of Ball’s evasion of justice demonstrate an effective deployment of his personal power against individuals and institutions that were trying to stop his ministry.

A major threat to Ball after his police caution and his resignation from the see of Gloucester in 1993 was the possibility of having his ministry curbed by some form of inhibition from Lambeth Palace and Archbishop George Carey. The avoidance of a public trial in that year had been a close-run thing. This escape from the full force of the law was arguably assisted by the bombarding the Director of Public Prosecutions with 2000 letters of support. Now Ball had to prevent the Church stopping him exercising a ministry among his supporters. These included public-school headmasters and others high up in terms of social position and status. George Carey’s reluctance to take decisive action against Ball may possibly be read as the conflict of two power systems. Although Ball’s institutional power had been weakened, he still retained considerable social power through his links and friendships with members of the Establishment. Many of these were still mesmerised by his charismatic power. Carey seems to have not wanted to be on the wrong side of the power that Ball could still muster to support him, even though as Archbishop, he could be said to have considerable institutional authority. He must have dreaded the problem for Lambeth Palace if even a small fraction of the supporters who had rallied to Ball’s support at the time of the caution had turned their attention on him. Carey, having risen to the top in the church from fairly humble social origins, seems to have been fairly easily intimidated by the disapproval of his social ‘betters’. I am, of course, speculating at this point, but in summary it is a reasonable reading of the available evidence to suggest that Archbishop Carey was simply afraid of the power that Ball could muster against him. The weak responses made by Carey, including the failure to share relevant letters with the authorities, are the actions of someone who is frightened of a power greater than his own.

Social power, institutional power and charismatic power are phenomena to be found in every institution, including the church. It is when they operate without being identified and understood that they can become a real problem. Ball, in possessing all three types of power, could and did become an extremely dangerous individual in the church. There were few checks and balances on his behaviour and the use of his power. Abusing this power was at the heart of his offending. He was also too powerful to challenge, even after his resignation and police caution. Even when the secular authorities caught up with him, the church still seemed not to understand how they had been manipulated by his narcissism and charismatic charm over a long period. What is likely to be revealed next week is a history of gullibility and naivety in the face of a predator who knew how to exercise power effectively for his own ends and fool everyone else in the process.