(* I am of course talking about JWs but don’t want this article to pop up on searches by the supporters of said group. Just as I don’t enjoy having my door knocked on, neither would I enjoy an online attack.)

My blog posts have, up till this point, been confined to examining the behaviour of Christian bodies. I don’t intend to deviate from this, but I feel it appropriate to bring to attention published material that sets out how Witnesses deal with uncooperative and dissident members of their group. I make no claim to have ever involved myself with the Witnesses so what I write is based solely on what they have written themselves. This material opens us up to a world-view and a mentality which may or may not help us to understand the mindset of other extremist cultic groups. I shall leave that for others to judge. What is true is that ‘religion’, as exemplified by the Witnesses leadership, can think and act in what seems to be a completely cruel and heartless manner towards some of their own membership.

Apart the practice of refusing blood transfusions, the practice of ‘disfellowshipping’ is the one that most disturbs the general public when encountering Witnesses. Two quotations of chilling brutality sets out the context of ostracism, as practised by the group. ‘The one who deliberately does not abide by the congregation’s decision, puts himself in line to be disfellowshipped’. One can only speculate what the words ‘abide by the congregation’s decision’ actually means. One imagines that it basically believing without question what one is told. A second quote: ‘any attachments to the disfellowshipped person, whether these be ties of personal friendship, blood relation or otherwise, must take second place to the theocratic disciplinary action that has been taken.’

I pause to consider what might be the meaning of the innocent sounding word ‘theocratic’. It literally means the rule of God, as opposed to other systems like democracy or even non-democratic systems like Marxism or Fascism. To the untutored ear it sounds like a good idea, in that brings divine values into society, rather than relying on the untidy methods of democratic debate for political decisions to emerge. In practice, there are always specially chosen groups of men, who have a ‘hot’ line to God and know exactly what his will is. History, even that of our own time, tells us exactly what theocracy actually looks like. Whether it is expressed in a Christian or Islamic form, it normally involves a fierce autocracy that suppresses any idea of cultural or social advance. It is conservative in its passionate embrace of the idea that nothing of any value can be discerned outside the group, or the society, it is trying to create. Education is about mastering the tools of literacy and numeracy but little more. Theocracy comes down hard on creative ideas or innovation, whether these are expressed among the Witnesses or in the so-called Caliphate in Iraq. To put it bluntly, you are more likely to survive in this ‘theocratic’ society if you have never eaten the apple of thinking for yourself.

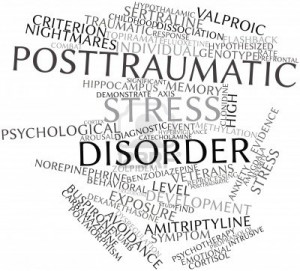

Further instructions about the treatment of the ‘disfellowshipped’ follow. “Those in the congregation will not extend the hand of fellowship to this one, nor will they so much as say “Hello” or “Good-bye” to him. … Therefore the members of the congregation will not associate with the disfellowshipped one, either in the K. Hall or elsewhere. They will not converse with such one or show him recognition in any way”. Further instructions specify: ” we also avoid social fellowship with an expelled person, This will rule out joining him in a picnic, party, ball game, or trip to the mall or theatre or sitting down to a meal with him either in the home or in a restaurant.” While it is true that there have been adjustments to this system over the decades, the ‘system’ still comes down heavily on anyone who even questions, even inside themselves, the teachings of the movement. What we witness in these instructions is that people are encouraged to cut themselves off from others and silence them, not on grounds of dislike but because the Movement decides that this is right. There is a justification for this behaviour offered when instructions state: ” If you shun a person enough leaving her down and without friends, she will have no other alternative but to reintegrate the Movement and submit again to its control.” This sounds like a generous slave owner trying to recapture runaways! One’s heart goes out to such survivors who are the subject of such barbaric treatment.

I need hardly say that the line of ostracism and shunning loved ones in the Witnesses movement has caused massive unhappiness worldwide. That a body of religious leaders, at the instruction of those set over them, should decide to fracture so thoroughly human relationships of people they know well, is incomprehensible. Such a system, according to these dreadful injunctions, invites no sympathetic understanding from the outside world. Indeed it is hard to imagine how an individual could get close enough to study their beliefs and listen to them without finding their sanity and sense of identity under attack. I am not encouraged, after reading this material, even to extend the hand of friendship to those who come knocking at the door. I am even less inclined to embark on any discussion with them, knowing that our perspectives on the Bible and God are so far apart.

Witnesses are clearly outside the mainstream of Christian life in this country, but it is clear that they operate in ways that are practised by a variety of extreme religious groups and cults. What is interesting and unique about the JWs is that they have actually printed instructions for local leaders which we can read and study without having to get close to the group. We can begin to understand a deviant world of belief and practice and recognise that however much we may be enthusiastic for God, their so-called ‘ theocratic’ pattern of church life, is one that holds absolutely no attractions.