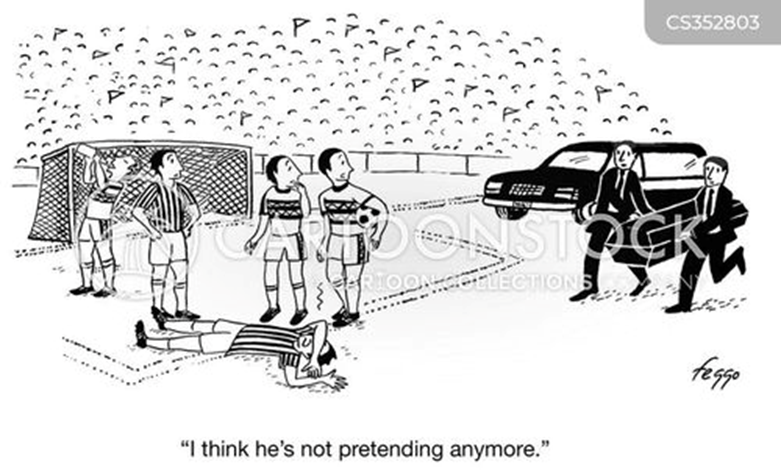

Many, perhaps most, of my readers will have watched the powerful video featuring Matt and Beth Redman entitled ‘Let There Be Light’. I don’t propose to analyse all the comments made by the Redmans about their experiences of working alongside Mike Pilavachi at Soul Survivor. But there was one telling remark made by Matt when he was recounting the difficulty of reporting Mike’s abusive behaviour to those in authority in the Church. The comment that came back, when Matt took the courageous and difficult task of disclosure about a close colleague, was something to the effect of ‘that’s just Mike’. In other words, the response of a senior churchman to a serious disclosure of abuse was to trivialise it and try to laugh it off. It needs hardly to be said that such a comment was insensitive and inappropriate. The jokey response failed Matt and, at the same time, it was failing many others in the organisation who were vulnerable to the predatory activities of Mike P.

Individuals who fail in their obligation to take action to stop abuse within an organisation are guilty of serious neglect. The guilt of those who have positions of leadership, responsibility and oversight is proportionately far greater than the ordinary members within a structure who have little power or influence. When scandals break in most secular organisations, the people at the top attempt to ‘do the right thing’ by resigning. This never seems to happen in the Church of England There appears to be a culture of hoping that the affair will blow over and that people will forget the role of shepherds who did so little to protect the sheep.

The church leader/trustee? who uttered those four words ‘that’s just Mike’ may never have pondered the likely damage caused to the Redmans, nor would he have considered the unhappiness and pain that was being unleashed on their future ministry by this inaction. The considerations that could possibly have entered the leader’s mind might have included one or more of the following.

- There is first the sheer hard work of taking someone to task for what may be criminal behaviour. Even if the behaviour reported does not constitute an actual crime, there may still be the need to cooperate with the police, solicitors etc., not to mention the phalanx of lawyers who work for the Church. The reason for laughing off a serious disclosure may simply be because the Christian leader knows that the path towards finding justice and closure for all involved is a long, tortuous and difficult process. Does anyone really have the time to manage and see through all the work demanded?

- The second reason for wanting not to be the one dealing with safeguarding complaints is that the likely respondent might be already known to the senior leader. In an organisation like the Church, individuals often have large circles of people they know directly and others they know through friends. Church networks, like the conservative evangelical world which is bound together by a shared experience of such things as Iwerne camps and university Christian unions, are not large. Public-school boys, the kind that were favoured in the Iwerne camp culture, appear to retain their ‘clubbable’ nature, and their loyalties to the institutions that reared them are often maintained with great devotion. Would an old boy of X school really be prepared to follow through with an accusation of someone with whom they played squash some thirty years before? Strong networking is of course not just confined to the evangelical tribes; we find such behaviour in other groups such as dining clubs with church links like Nobody’s Friends.

- One of the reasons for a reluctance to bring scandals into the awareness of the wider church group is the claim that the exposure of misdoing always damages the institution. A frightened abused young woman might be told by a member of staff not to bring accusations of assault against a leader, for fear that it will damage the leader’s important ministry. In fact, we see over and over again that the opposite is true. Suppression of scandal over a period of time does unbelievable damage to an institution. Most people would say that they can accept the inevitability of serious misbehaviour by an individual from time to time. It happens, but the institution can usually recover if the right protocols are followed. What is totally disastrous is the collusion of leaders in evil behaviour by refusing to expose it the moment they were first made aware. Cover-up is deeply corrosive to the reputation and integrity of the Church. Last year we saw the imprisonment of Martin Sargeant, an unofficial ‘fixer’ for the Diocese of London. It would appear likely that, to sustain his reign of dishonesty and the gradual theft of 5 million pounds from the diocese, he had gained the ‘see no evil’ cooperation of others, including members of the clergy. It is also hard to see in the case of the corrupt bishop, Peter Ball, how he could have continued so long with his nefarious behaviour if he had not had the tacit support of others, including clergy and senior bishops.

These three suggested reasons for laughing off Matt’s disclosure of abuse and inappropriate behaviour -sheer unwillingness to do the necessary slog of upholding justice, bonds of friendship or acquaintance and the fear of compromising the institution in some way – are likely to persist in the church’s life. The only solution, which will make these three impediments to justice impossible in practice, is the Professor Jay solution. That is the one that provides a completely independent structure for all safeguarding matters. Returning back to Matt Redman’s failure to find help from the system of oversight in the Church of England, we sense an inertia and closed shop atmosphere that will typically always place loyalty to the institution above truth. If that is the case, particularly among the senior members of the church, that will have a deeply corrosive effect on the life of the whole institution. If we ever reach the point where an acquiescence in protecting the system becomes a qualification for high office, then the death of the whole structure becomes only a matter of time. Young idealistic individuals will see the clerical profession, not as an opportunity to serve God’s people, but as the opposite, the gratification of a narcissistic need for status and power. The sleaze of UK politicians has thinned out the ranks of good people seeking to enter Parliament. If at any time young people see the clerical profession as a danger to their integrity, then the only ones still able to find fulfilment there will be those for whom integrity and honesty are of no concern. If the Church has only such people as its leaders, is there any point in lay people becoming members? One question in wide circulation in the 90s was ‘is your church worth joining?’ In the case of a Church that tolerates its leaders ignoring the needs of the suffering and abused, the answer has to be resounding No!