Gospel Reading for Lent 3. John 2: 13-22

by Martyn Percy

There’s a lovely moment in C. S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, where the three children are introduced to Aslan. Aslan, let us remember, is a lion. A big one. They eat meat. Including children and other animals. When Aslan is being entertained at Mr. Beevor’s house, Lucy, one of the children, asks rather anxiously and curiously, “is Aslan safe?”. Mr. Beevor replies, “oh no my dear, he’s not safe. But he is good”. Can you be good, but also carry threat? Well countries manage it. Communities too? I’ve even heard that parents manage it too.

Here are a couple of questions for our time. How do you love and care for a world that mostly enrages you, with all our political failures and social stigmatization and deep social divisions? And how do you care for and love the Church, which far from being that ark of salvation it is called to be, seems to enrage you even more? As the Civil Rights campaigner John Lewis said, ‘there is never a wrong time to do the right thing’.

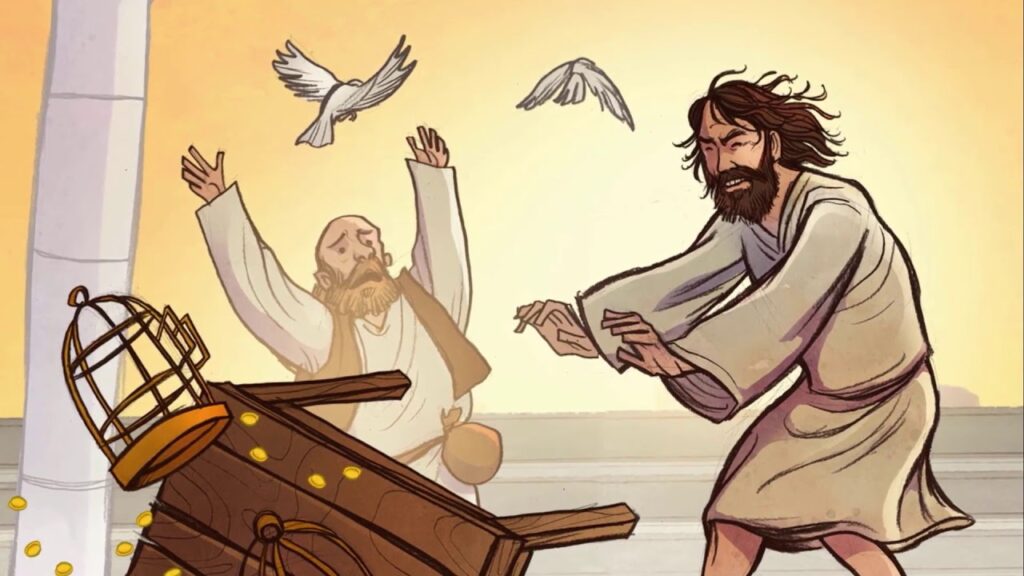

But is it ever right to be angry – even furious – at injustice? The gospels answer us: Yes. And John’s account of Jesus cleansing the Temple (John 2:13–22) gives us some clues. Jesus is supposed to be a peaceable and wise teacher. But he creates mayhem in the Temple, and upsets all the people going about their lawful trading in dubious ‘religious tat’ and offerings. He goes the whole hog too, driving them out with a whip that he made himself. That took time, so this is a planned attack.

The story in John’s gospel is a meditation on Jesus’ manifesting wisdom, and also his alleged foolishness. Because Jesus spends much of his ministry being cast not as a hero, but as something of a loose cannon; and possibly even a deranged prophet. His words and works are prejudged by his critics, because even in first-century Palestine, the social and theological construction of reality seems to prejudice many people’s perceptions of Jesus.

To casual onlookers, turning out the traders from the Temple is a foolish thing to do: they don’t mean any harm, do they? Why pick on merchandizers selling ‘religious tat’, offerings and souvenirs? Or moneylenders, who we all have need of? We all accept this. Jesus, in contrast, does not; and as in other cases, behaves ‘rather badly’. Behold! He eats and drinks with a bad crowd; he finds himself narrated as a glutton and a drunkard. So Jesus says, somewhat cryptically, that ‘wisdom is vindicated by her deeds’.

But there is a difference between hot anger and cold, perhaps righteous anger. Jesus actually went away and made the whip of cords he used on the hapless traders. This is a cold premeditated attack; not a rush of blood to the head. He has, as the Epistle of James puts it, ‘been slow to anger’ – but he’s got there. And now he’s meting out some discipline.

Wisdom is key. Because the second part of the gospel story outlines how the seemingly wise and righteous appear not to be able to see what is front of their noses, whilst the apparently foolish and unrighteous seem to have perceived. So Jesus’ action in the Temple – reckless, violent and apparently intemperate – contains quite a radical, strong message. It conveys wisdom. That sometimes, breaking our frames of reference with such sharpness and anger is the only way to get people to see how foolish they have been.

This is the key to understanding the incident: it is about breaking a culture, and smashing the prevailing frames of reference. So, Jesus is acting something out in this narrative: there was really no point at all in trading up from a pigeon to a dove. Neither sacrifice would bring you closer to God; you are wasting your money. There was no point in going for the “three-for-two” (TFT) offer on goats; or the “buy-one-get-one-free” (BOGOF) offer on lambs.

Much of the gospel of John is all about being reconciled to what has been hidden, and looking deeper into what has been revealed. And to seeing beyond the apparently obvious: to find the wisdom in apparent folly. And this is why Jesus’ anger in the gospel is so interesting in this story. For it seems not be a hot, quick irrational ‘snap’; but rather a cold, icy anger.

Rather like Arnie (a robot from the future) in the film The Terminator, he’s seen the Temple, and said to his audience: ‘I’ll be back’. As Harvey Cox noted in On Not Leaving it to the Snake (1968), the first and original sin is not disobedience. It is, rather, indifference. We can no longer ignore the pain and alienation that others in the church experience – and especially when this is because of the church. Indifference is pitiful, and it is the enemy of compassion.

There are three things to say in relation to Jesus’ emotional temperament here. First, what is Jesus so upset about in the Temple? It seems to me that it lies in assumptions: about the ‘natural order of things’; about status and privilege; about possessions; about prevailing wisdom. This is about, in other words, unexamined lives and practices lived in unexamined contexts. Everyone is blind. Jesus’ action forces us to confront the futile sight before us. His anger forces us to look again. (On this, see Lytta Bassett’s excellent Holy Anger: Jacob, Job, Jesus, London: Continuum, 2007).

Second, the story chides us all for that most simple of venial sins: overlooking. The trading has been happening for years and years. It is simply part of the furniture; it barely merits a look, let alone comment. Jesus, of course, always looks deeper. But the lesson of the story is that, having looked into us with such penetration, his gaze then often shifts – to those who are below us, and unseen. That is, those with less wealth, health, intelligence, conversation and social skills; or just less life.

Third, the besetting sin is that the Temple traders accept the status quo. The story has one thing to say about this: Don’t. Don’t accept that a simple small gesture cannot ripple out and begin to change things. Don’t accept, wearily, that you can’t make a difference. You can.

Sometimes the change may be radical; but more often than not, change comes about through small degrees. Reform can be glacial, and adaptationist. We need to stop waiting and start acting. Nigel Biggar writes that:

True prophets are ones who don’t much enjoy playing prophet. They don’t enjoy alienating people, as speakers of uncomfortable truths tend to do. They don’t enjoy the sound of their own solitary righteousness and they don’t enjoy being in a minority of one. True prophets tend to find the whole business irksome and painful. They want to wriggle out of it, and they only take to it with reluctance. So beware of those who take to prophesy like a duck to water, and who revel in the role. They probably aren’t the real thing. (Nigel Biggar, ‘On Judgment, Repentance and Restoration’, a Sermon preached at Christ Church Cathedral, 5 March 2017, and quoted in Martyn Percy (ed.), Untamed Gospel: Protests, Poems, Prose, London: Canterbury Press, 2017)

True prophets can be thoughtful, kind and cautious creatures. And angry. Caricatures of raging fire-storming preachers should be set aside. True prophets are more emotionally integrated. They are pastoral, contextual and political theologians. They care about people and places. They have virtues such as compassion, care, kindness, self-control, humility and gentleness. But they have passion and energy for change too; often reluctantly expressed, and only occasionally finding voice in anger. Pure compassion can be quite ruthless. (Ask any parent who loves their child.)

The scandal of our churches and church leaders is that they prefer to survive rather than be true; they choose optics over justice; they privilege pride our reputation over honesty and integrity. To Jesus, this is a scandal. To the world, it is a scandal. To emerging generations it means a lengthy sojourn in the wilderness of ever-increasing indifference.

This gospel asks us to think hard about how we channel our anger about injustice. Some will call you mad or drunk for doing so. But sometimes, the only response to injustice is righteous anger. Not just shouting and raging. But acting the anger out. “Let the reader understand” (Mark 13: 14).

The Very Revd Prof. Martyn Percy