Almost exactly one year ago, Surviving Church carried my blog piece on trauma-informed practice in safeguarding matters. https://survivingchurch.org/2022/12/10/trauma-informed-therapy-some-lessons-for-the-church/ It was a continuation, among other things, of my long-held dissatisfaction over the way that abuse survivors frequently encountered something other than compassionate understanding when seeking to tell their story to authority in the Church. I had noted some time ago that the National Safeguarding Team did not employ a single psychotherapist on its staff. The dominant NST skill set seemed to lean towards management I was thus pleased to see that Sarah Wilkinson, in her recent review of church safeguarding protocols, was anxious to emphasise the importance of trauma awareness among those who manage safeguarding at every level. This is the first sentence of her recommendation on this theme. ‘Everyone involved in decision making about safeguarding issues at the NCIs, from the Archbishops to case workers and including all members of the Archbishops’ Council, should have mandatory training on trauma-informed handling of complainants, victims and survivors.’ Wilkinson is evidently concerned at the high levels of stress and trauma being carried by survivors. This is exacerbated by the fact that many of those representing church bodies, who sit on powerful committees and deal with the survivors, has little or no prior understanding of the trauma and experience of being such a survivor. She rightly discerns that when highly vulnerable survivors are brought face to face with people with little empathy or understanding, the level of additional suffering endured will be considerable.

When we look at the Church as a whole, the question that might well be asked by an abuse survivor is whether this institution is ever a safe place to enter. The answer to this question may depend on our being able to discern where the particular local manifestation of church stands along a spectrum of what we can call abuse sensitivity. At one end of this spectrum, we find compassion and effective care. Here we encounter a readiness by a church to provide every conceivable form of help to survivors. There will be included spiritual, emotional and practical support over as long a period as is necessary. At the other end of our imaginary spectrum, we can envisage a harsh cold and bureaucratic indifference to the survivor. There would be no understanding of the pain and trauma, and even the existence of damage and vulnerability would be a cause of annoyance to the one trying to deal with the situation. The judgement about where the current levels of care in the Church are to be found has to be a matter for the discernment of the observer in each situation. At present, based on my listening to what people are saying, the consensus of opinion seems to find that the typical experience of care by the church is closer to the negative end of the spectrum. What is experienced is more likely to resemble what is routinely found as a bureaucratic or managerial response to this kind of issue.

Churches generally fall somewhere in-between the two extremes of the abuse response spectrum in the attitude they show to survivors. An inept or hurtful response to a survivor seeking help may of course be as much to do with ignorance and lack of training as it is an act of deliberate cruelty. The fact that amateur clumsy responses are retraumatising victims should, nevertheless, be a matter for concern. To say that so-and-so did not mean to hurt or trigger a painful reaction in an individual, already vulnerable, is not a good look for people who are claiming to preach a message of good news, love and healing to a hurting world. There is good news in all this, though one has to understand these words in a non-biblical sense. The good news is that the secular discipline of psychological healing does understand how to respond to trauma and can teach this skill to Christians. At the very least, church leaders and representatives need to learn from these experts how to stop heaping additional hurt on the vulnerable victims of church-based power abuse. This, in essence, is one important challenge that Wilkinson is presenting to our Church. We ignore it at our peril.

The contemporary discipline, practised by professional carers who are faced with clients afflicted by trauma, is one that offers hope to trauma victims and survivors of every kind. Various approaches can be found in the therapeutic literature, and I make no claim to any expertise in this area. Wilkinson was clearly, in making her recommendation for trauma-informed training to be provided across the Church, familiar with this material. What follows here is an overview of what one centre in the States, the Buffalo Centre for Social Research, describes as Trauma-Informed Care (TIC). Their helpful initial summary definition goes as follows. ‘Trauma-Informed Care calls for a change in organisational culture, where an emphasis is placed on understanding, respecting and appropriately responding to the effects of trauma at all levels.’ The short summary that follows this broad description of TIC, brings to our attention a number of observations about the wide prevalence of trauma in individuals seeking any kind of help. Because the presence of trauma is so widespread, the ability to respond appropriately has to be built into the culture and practice of all care providers. Their task is to provide appropriate support from the outset, providing a caring response towards any possible trauma victim. This support must be shared in such a way that it does not lead to the exacerbation of the existing trauma symptoms. One helpful question to be asked routinely, and which well articulates the assumptions and culture of TIC, is not ‘what is wrong with this person?’ but ‘what has happened to this person?’

The Buffalo approach makes a number of other helpful suggestions about the possibility of re-traumatisation. When an abused person has to experience a trauma over and over again through repeating the details to different agencies, this can be so painful that the survivor may be unwilling to cooperate with otherwise well-intended offers of help. Sensitivity over such things as the location of an interview with a senior official need to be carefully looked into. A TIC approach will ‘respond by changing policies, procedures and practices to minimise potential barriers.’ The staff dealing with abused individuals will always be alert to signs of trauma and thus lessen the danger of any re-traumatisation.

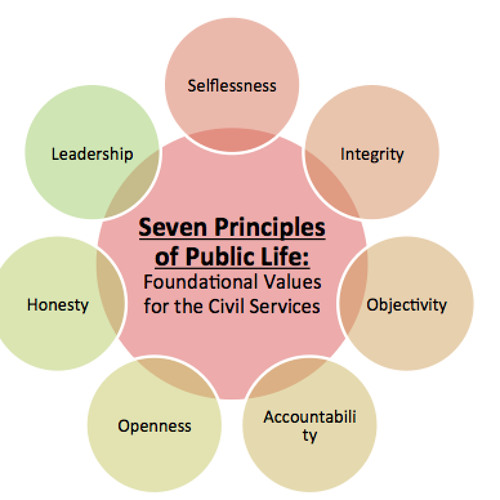

In some ways this blog piece follows the pattern of the previous one looking at the Nolan principles. TIC, it is clear, is also about values and culture rather than institutional competence. Instead of the seven Nolan principles we have the Five Guiding Principles of TIC. These are safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness and empowerment. In some ways each of the words is self-explanatory. Most of the values they describe focus on the importance of helping the survivor to feel safe and protected from any further exploitation of their vulnerability. Alongside this provision of safety and protection, there is also a recognition of the need to help the survivor to regain his/her own power and find the resilience to begin the process of healing. The Church often refers to the ideal of putting the survivor at the centre of the process of safeguarding. What we often find is an organisation in a state of panic, believing that its primary task is to protect its reputation (and assets) from the legitimate claims of the wounded and damaged. TIC presents us with another model, one that respects the need and the longing of survivors to heal so that they can continue their lives with new hope for their eventual complete wholeness.

Although I cannot claim to have mastered all the other detail of Sarah Wilkinson’s thorough and detailed review, it was helpful that she chose to shed some light on this major issue concerning trauma in the safeguarding process. Survivors are never a problem to be managed; rather they are a group of human beings who have emotional and practical needs as the result of abuse/trauma they may have suffered. Their practical needs may include the recovery of lost income and livelihoods and the availability of professional support from experienced therapists. Hopefully all these professionals will understand the meaning of trauma-informed help. If some of this sensitivity were to be a required part of the wider culture of the CofE, as Wilkinson recommends, the Church everywhere would become a more wholesome organisation, built on the gospel principles of compassion and love.