by Anonymous

An occasional series looking at how ordinary words and terms have been redefined in the Church of England (CofE). Others in the series to look out will feature mutual flourishing, vulnerable adult, pastoral care, equality, collegiality, mission, appropriate, growth and accountability. And of course, the term ‘safeguarding’. This week, we take a look at ‘independent’.

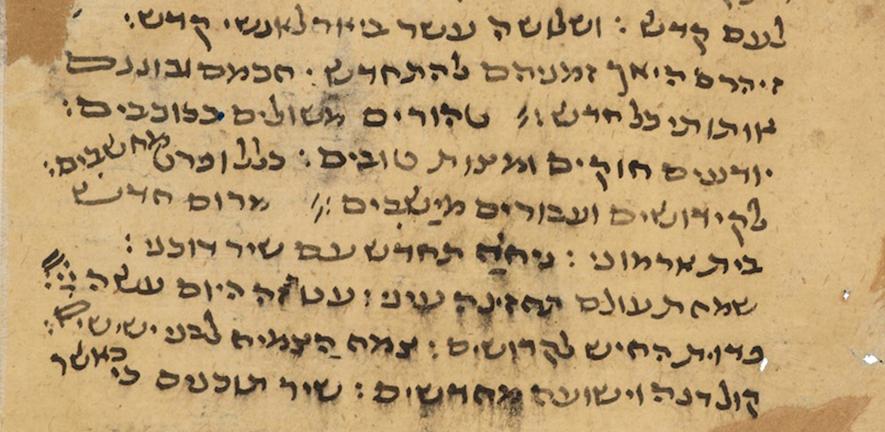

Readers of this blog may have a fond recollection of the launch of The Independent newspaper in 1986. It was memorable for many reasons. This was the first broadsheet newspaper to be launched in the UK for 112 years. The founders of the newspaper – dissatisfied with the ding-dong battles between Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch slugging it out in circulation figures, scoops and advertising revenue – sought to establish a newspaper free of mogul-ownership.

One of the more striking features of the newspaper was its marketing, with Paul Arden and Tim Mellors leading the team at Saatchi & Saatchi responsible for creating the advertising campaign. Who can forget the giant billboard posters: “It is. Are you?”. Just four words, and then the title of the newspaper. As zeitgeist captions go, hard to beat.

Yet the Archbishops’ Council have rubber-stamped the appointment of Meg Munn as the new chair of the Independent Safeguarding Board (ISB). Munn takes up post this month. This comes at a delicate moment in the gestation of the ISB. The two board members, Jasvinder Sanghera MBE and Steve Reeves CBE, have recently issued a number of statements and reports stressing the need for the ISB to become an authentically independent body. You’d think that request for independence would be granted? Think again.

The Archbishops’ Council has responded by imposing Ms. Munn as the new Chair. She already sits on or chairs other CofE safeguarding panels. She is not independent. Moreover, more than fifty survivors have written to the ISB to protest. They do not have confidence or trust in Ms. Munn. The likely incontinence between the NST, NNSP, NSSG and ISB is now a certainty. There is no proper data-related ISA (Information Sharing Agreement) in place. Anything communicated to Ms. Munn in one forum cannot avoid leakage into another.

The Archbishops’ Council don’t care a jot about any of this, because when you dominate an institution and its culture, words mean what you say they mean. Take a word like ‘independent’. It means ‘free from outside control; not depending on another’s authority’ (e.g., “the study is totally independent of central government”). But this is not the definition applied by the Archbishops and most bishops. In their case, ‘independent’ means “it wasn’t me that did or decided this: it was s/he, her/him, they/them…but they came to the same conclusion as me, and honestly I did not influence their decision…and they are not me, so they are independent”. In other words, ‘independent’, in episcopal hands, means a separate person agreeing with a decision the bishop has already made.

In case you doubt this Orwellian, Kafkaesque and Lewis Carroll Dictionary World, you may need to remind yourself that the CofE has no written conflict of interest policy. That is partly because “thoughts and prayers for you at this difficult time”, “we have offered pastoral care” and “it was a difficult decision, but I can’t comment further or give my reasons” are what are usually substituted for truth and justice in the CofE. Time and time again.

The last thing your average bishop wants is any independent scrutiny, external accountability or regulation. God forbid! The CofE is a large unregulated body, and in a literal sense, a law unto itself. Employment law, gender, discrimination, pay and conditions – all testify to a culture that works with its own standards (which would be unlawful outside the CofE) Having its own system of ecclesiastical law means it can (almost) get away with murder.

Well, certainly a few suicides – which in any secular body or organisation would prompt a public inquiry, much soul-searching and several sackings – but barely causes a ripple in the CofE. So, after the tragic gas-lighting of Fr. Alan Griffin and which led to his suicide, the senior diocesan officials carry on regardless, safe in the knowledge that any ‘lessons learned review’ will have terms of reference set by the accused, and be conducted by those whose main concern is to protect the reputation and optics of those who might be criticised. This is a serious pathology within an institution, this is an advanced case of Truth Decay.

Of course, it is true that a term like ‘independent’ can be used in a rather pliable way. My local coffee shop is ‘independent’, by which it means it is not a branch of Costa, Starbucks and the like. But my local independent coffee shop has three branches. Next door to the independent coffee shop is the independent bakery – it has seven outlets. OK, it is not exactly Greggs, I grant you. But if the bakery had 40-plus outlets, is this now an ‘independent chain’? The term ‘independent’ is a commercially-positioned identity. It connotes local, and not being owned by some faceless foreign conglomerate. It may even mean it makes its own pastries rather than buying them in bulk. Fair enough.

But when the CofE uses the term ‘independent’ in safeguarding, what does it mean? Is it “free from outside control and not depending on another’s authority”, or the more commercially local definition? No. Plainly, it is a PR term, and absolutely nothing remotely proximate to genuine independence.

Thus, the Diocesan Safeguarding Advisor (DSA) in your diocese will sometimes be referred to as independent. But they are paid by the Diocese, accountable to the Diocesan Board of Finance, work in Diocesan HQ, and ultimately be accountable to your bishop. (So, good luck with your complaint to the DSA about your bishop’s recent handling of X or Y…how is that investigation progressing? Seems a bit slow…and s/he’s not “stepped back from ministry” as required of all other clergy, pending outcomes…hmm, strange that, strange…).

Last year I wrote to both Archbishops to complain about the fact that the (then) Chair of the ISB, Maggie Atkinson, was not acting independently, and instead seemed to be conducting her work in a manner that was partial and protectionist of existing power interests, including church lawyers, senior officials and PR agents. The Archbishops waived away these objections in their first sentence: “we obviously have a different definition of what ‘independent’ means”.

They went on to explain that the way they used the term had to be qualified, and to factor in that as the Archbishops’ Council were paying for the ISB, yes, of course, to some extent they were inevitably controlling it, and had authority over it. But the ISB was still ‘independent’, they maintained – in a way that one might argue the Isle of White is unattached to England. Or I am independent from my partner.

Or the Basingstoke branch of Costa is from the ones in Basildon, Bicester and Barnet. I mean, those Costa branches are not physically joined together, are they? They have different staff, variable turnovers of income, dissimilar customer profiles – so in a sense they are independent of each other, aren’t they?

Put like this, then pretty well everything in the CofE is independent of everything else in the CofE, and that is also sort of true, isn’t it? Parishes are independent of each other. Clergy too. Dioceses, when it comes to questions of maternity leave, housing allowances, moving expenses, employment…well, yes, they’re all independent of their neighbouring dioceses. You see, having your own definition of words really can work awfully well in certain kinds of cultures and kleptocracies (i.e., 1984, Handmaid’s Tale, etc).

So, when the Lead Bishop for Safeguarding asserted at General Synod that the ISB was ‘independent’ he was not lying. He was just using the word in a rather unconventional way that is different to the rest of the population.

When IICSA demanded independent oversight of safeguarding in the CofE, it was of course left to the Secretary General of the Archbishops’ Council, Mr. William Nye, to properly interpret and translate the term ‘independent’ into a concept that those inside the CofE could work with. Because if ‘independent’ was used and deployed in the conventional sense in the CofE, then bishops would lose power and authority in safeguarding, and be open to challenge. IICSA surely didn’t mean that to happen, did they?

So here are three clusters of questions to ponder the next time you hear your bishop, DSA or some senior official in the CofE say there has been an “independent investigation” into some safeguarding matter or other. Just ask yourself the obvious questions, and put yourself in the position of being on the receiving end of the implementation. Ask yourself if you are comfortable with the standard of truth and justice operating. Or, feel rather betrayed?

The Set-up:

Who made the complaint? What do you know about the accusation? Were there other charges, victims or complaints? Who set the terms of reference for the investigation? Who paid for these to be set? Did you have any input into this set up, either as a victim, witness or as accused? Is there anyone involved at this stage who has a conflict of interest? How would you even know, or challenge this?

The Execution:

Is the legal firm advising on the investigation process the same one that the Diocese and the Bishop have? Do you have any legal representation, or even legal rights? Is the investigator regulated or accountable, and if so, how and to whom? What evidence is going to be considered? How was the scope of investigation communicated to you?

The Outcome:

When a decision is made, what rights do you have as a victim or as the accused? If you discover that there have been false witnesses, or that evidence has been redacted, supressed or co-ordinated, can you do anything? Is your Bishop in this acting as your pastor, prosecutor, judge, jury, employer – all of these, or maybe none of them? Can you trust this system in which there appears to be no accountability?

In conclusion, it is these sorts of questions the independently-minded Jasvinder Sanghera and Steve Reeves were beginning to grapple with. Whatever the shortcomings of the nascent ISB – largely attributable to the abysmal resourcing and obstruction from its parent body the Archbishops’ Council – Sanghera and Reeves at least understand independence, and also what a problem conflicts of interest are for the destruction of trust and confidence.

This explains the imposition of Ms. Munn as the new chair. She is in post to remind the rest of the CofE that ‘independent’ is a meaningless term in a church run by autocratic and unaccountable leadership. If Ms. Munn had any decency, integrity and probity, she’d refuse to take on the role. Those who have imposed her are banking on her toughing it out. That, at a stroke, renders the concept of independence void, and simply leads to a total incontinence with the data and lives of victims, survivors and complainants already abused through CofE safeguarding.

As a postscript, we note that The Independent was eventually bought by Tony O’Reilly’s Independent News and Media Group, before being sold to the Russian oligarch Alexander Lebedev in 2010. Lebedev, like Putin, is a former KGB officer. Lebedev also owns a newspaper with Mikhail Gorbachev. In 2017, Sultan Muhammad Abuljadayel bought a large stake in The Independent.

In theory, The Independent could run a critical story on Lebedev, Gorbachev or Abuljadayel. But it doesn’t seem likely, does it? You might then ask yourself if it is not a little impertinent, and indeed slightly misleading, to be the owner of a newspaper called The Independent?

We are back deep into CofE safeguarding terrain here. ‘Independent’ is a commercial and marketing-PR term as much as it is a legal one. The Archbishops’ Council hope you will believe they are using the term as a legal or regulatory word. In truth, they are selling you a huge con: it is only their marketing-PR term.

As I say, once you realise that the DSA works for your bishop, it isn’t going to be easy to raise your concerns about episcopal safeguarding conduct. The ISB might have been a useful avenue that opened up an alternative route. Ms. Munn’s appointment puts a huge roadblock firmly in the way. The advertising campaign for The Independent once teased “it is, are you?”. The CofE, with Munn’s appointment, shows that it has its own secret advertising campaign well underway. But there are no teases here. “Independent Safeguarding? Certainly not! Why in God’s name would we?”.