One of the insights given to those of us approaching old age is the recognition that the wisdom you have now obtained was not there thirty or forty years before. As a retired parish priest, I see clearly how some decisions made in the past were not always the best ones. I am not thinking about things that could have harmed people, but judgements made that may have affected the general progress of a parish. Back a few decades (I shall not be more specific), I was faced with the arrival of a clergyman (we will call him Peter) in my parish who had taken early retirement on health grounds. My 2021 self would now ask some very penetrating questions about the nature of the ‘health grounds’. I should at the very least have made a phone call to an archdeacon to find out a little more. Probably in this case, I would have picked up the message that there was something to be cautious about. On the face of it Peter had had a lively ministry, albeit of a charismatic flavour. This was, however, the only style he seemed to understand, and it was not where any of my then congregation were. The sermons that Peter preached were volatile and unpredictable. Displays of emotion in the pulpit about relatives who were not ‘saved’ did not edify but rather embarrass. The liturgy was also subject to random editing which did not stand up to any kind of theological consistency. As time went on, he began to show signs of mania which are not the product of a healthy charismatic spirituality. I have always been tolerant of charismatic styles of prayer and it was probably this tolerance in my younger self that allowed a difficult situation to continue longer than it should have done. It did eventually resolve itself as Peter found a much more congenial audience for his style of preaching among the network of independent congregations around. They welcomed a new voice to their services.

My exposure to charismatic forms of preaching/ministry did not start from the experiences I had with Peter. My pre-Peter experiences had been reasonably extensive, and I certainly feel that I had been able to grasp the importance and appreciation of these styles of spirituality to a ministry of healing. Healing and the support of healing ministries took up a significant part of my ministry and I served some years as a Bishop’s Adviser. This role involved me with becoming sensitised to a variety of theological styles when practising this ministry.

It was tempting right back in the 70s when I first encountered charismatic phenomenon and preaching, to think of it in entirely theological terms. To introduce any kind of psychological insight in assessing it seemed somehow blasphemous. The Holy Spirit was, to all appearances, operating directly in the lives of Christian individuals and transforming lives and making them holy. This direct unmediated access to the Holy Spirit was similar to other claims that conservative Christians were making about the text of Scripture. Anything as pure as the ‘unmediated Word of God’ had to be beyond any kind of human criticism. This uncritical approach to the manifestations of the Spirit was quite simply another form of fundamentalism. Both the Bible and the Spirit quickly could however, become tools of oppressive power in the wrong hands. We can see that the entire charismatic movement has been damaged by such claims for the ‘infallibility’ of the Spirit. Statements like ‘God is speaking to me and revealing his will’ enter into the discourse of the leaders. This kind of grasping of power by Christian leaders, using the tool of text-quoting and appeal to spiritual phenomena, is unlikely to be healthy. Just because followers long for certainties in the Christian journey does not mean that Christian leaders should spoon feed them As readers of this blog will know, I have never allowed the mere quotation of a biblical text to resolve a theological issue. Finding ‘truth’ in the miasma of text-quoting and the multiplicity of theological traditions that we have, is endlessly complex. Christians may long to possess certainties but there are many reasons to suggest that this is not easily delivered. The Bible is not, and never has been, an oracle full of proof texts. Culture and the rules of meaning within language will throw up ambiguity and nuance at every turn. It is what makes the Bible and the theology it contains an endlessly fascinating study but, for some, this does not provide the certainties for which they crave.

Pentecostal/charismatic-style preaching with its double appeal to unmediated pure reality of God through scripture and experience will have tremendous drawing power because it meets a craving for certainty. Being entranced by this link to certainty will also mean a strong attachment to the one teaching and preaching in the church. In what I, and many other Christians, would consider to be a kind of blasphemy, there is a process which transforms an ordinary fallible human being into a super-human oracle of God. By demonstrating the power of the Spirit and being the only legitimate interpreter of the Word of God, the minister/pastor claims all power to himself. Someone who believes that he indeed has such extraordinary power may also be on the way to a manic breakdown. This is what appears to have happened to Peter before his early retirement and his arrival in my parish.

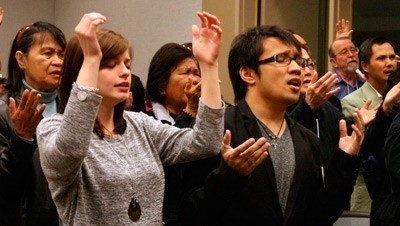

Why do people flock to such congregations where the preacher may sometimes exhibit mania and other disturbing facets of the narcissistic personality that we have talked about on other occasions? Something I have recently read about the charismatic leader in all walks of life explains this conundrum very elegantly. One prominent feature of many groups and that includes many charismatic/Pentecostal congregations is the strong sense of us/them. Belonging to a group that that many such groups carry as part of their identity. Part of the church’s corporate memory will then consist of the way that there was once this traumatic separation from another group. This may have involved a parting of ways from another denomination. There will thus be a major ‘them’ from the past as well as a number of other thems in the present. We have contending against us the unsaved, the mockers of the faith and the liberal intellectuals. It will take a relatively modest level of rhetorical skill for the preacher to incubate successfully that sense of separateness and estrangement felt by a congregation. People enjoys this feeling of being specially chosen when compared with the ‘other’. Separateness make them aware of themselves as distinct from their Christian and other neighbours. It is not hard, as we have seen before, to back up from Scripture this strand of teaching. By emphasising this line of exposition, the congregation can be persuaded to give up their thinking selves as a way of suppressing any dissonance that they may feel. That will allow them to fall in with the dominant opinion, that of the leader or preacher.

The book I am reading explains how the preacher/charismatic leader is subtly encouraging one part of the brain to become dominant. It is well-known, even in motivation/leadership courses, that people working for a corporation are seldom motivated merely by appealing to the rational part of the brain. It is the emotional brain, the amygdala, the more instinctive part of the brain, that needs to be activated for real changes in behaviour to take place. It is this part that is activated when the body senses some danger or something causing fear. In a congregational setting the ‘enemies’ of faith are named as threats and this will get the amygdala activated. This will successfully override the pre-frontal cortex, the part of the brain that uses reason for decision making. Such group thinking is also common in a political context. The leader, having roused an audience to fear the other, whether an idea, a group or an individual, can then keep them in a state of expectation and longing to have provided for them the ‘answer’ that will remove the demons out of sight.

My appreciation of charismatic preaching and practice has to be qualified by my dislike, even loathing, of methods of manipulation that involve the subtle use of threats and fearmongering. The path to a holistic appreciation of the Christian good news should surely involve the reason, the thinking part of the human person. Can we ever afford to hand over ‘faith’ to the irrational and the primitive functioning of the human brain? There is a time for the emotions and the feelings to take a prominent place in our religious life. Supressing reason and discernment is not the way to do this in a healthy way.