Readers are invited to add their names to this letter by following the link to Change.org petition https://www.change.org/p/the-micah-6-8-initiative

To: The Rt Hon Baroness Stowell of Beeston, MBE

Chair of the Charity Commission

102 Petty France

Westminster

London SW1H 9AJ

Tuesday 11 August 2020

Dear Baroness Stowell,

We write as interested parties to ask that the Charity Commission exercise its powers of intervention to address the failures of the Archbishops’ Council of the Church of England (charity number 1074857) to devise a safe, consistent and fair system of redress to all parties engaged in safeguarding complaints. The structures of the Established Church are complex with responsibilities both devolved and diffuse. In addition to 42 Dioceses operating local jurisdiction, there is a National Safeguarding Team (NST), reporting to the Secretary General (William Nye) through a National Safeguarding Director (Melissa Caslake). Policy is devised and guidelines issued by the House of Bishops; there is a Lead Bishop for Safeguarding (currently the Bishop of Huddersfield, Jonathan Gibbs) working with two assistant Bishops (a relatively new innovation) and with further responsibility undertaken by the National Safeguarding Steering Group (NSSG) chaired by the Lead Bishop with its members appointed by the two Archbishops. In addition, there is a National Safeguarding Panel (NSP), “set up to provide vital reference and scrutiny from a range of voices, including survivors, on the development of policy and guidance” with an independent (external) Chair, Meg Munn. The power to suspend under the Clergy Discipline Measure is reciprocally exercised by the two archbishops in cases involving themselves.

There is now some urgency over addressing the impaired transparency and intermittent accountability of the NST. Within such a complex structure, it is extraordinarily difficult for aggrieved parties to secure redress of individual grievance, for questions to be raised, or for policy and its implementation (or lack thereof) to be challenged. We address our complaint to the Archbishops’ Council as the body with ultimate responsibility, established by the National Institutions Measure 1998. It is accountable to the General Synod but is not subordinate to it. In effect, it acts as the national executive of the Church of England.

We are writing as, despite raising significant questions over policy and practice, there is only a nominal institutional acceptance of the need for reform. True, there is now a process underway for a replacement of the widely discredited Clergy Discipline Measure 2003, and the final report of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) into the Anglican Church is awaited. However, the continuing flow of cases of injustice leads us to seek early intervention from the Charity Commission. We do this with reluctance, having tried and failed to secure redress through multiple complaints across the structure.

The signatories to this letter come from a wide range of backgrounds, and all are people with interest in and experience of the current system, policies, and culture within the Church. They include aggrieved complainants, respondents, lawyers, members of the General Synod, clergy, laity and the contributing authors to the book Letters to a Broken Church (published in July 2019) which collected a range of essays exploring the many ways the current system fails all involved.

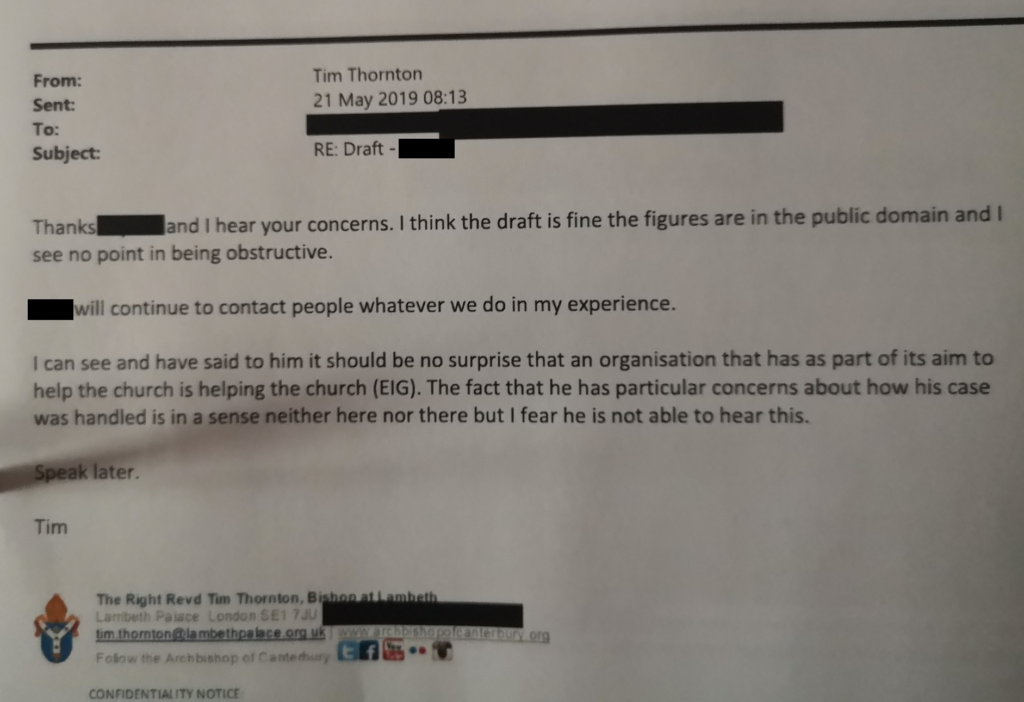

Much of the discontent centres upon the secretive world of the National Safeguarding Team (NST) core groups, which act in ways reminiscent of the Star Chamber, synonymous with the selective use of arbitrary unaccountable power, concentrating effective control of process in the hands of a very few, who exercise wide-ranging discretions afforded by guidelines devised by Church House administrators and issued by the House of Bishops. Such discretion includes ignoring those very guidelines. Even then, these guidelines are demonstrably inadequate, and are not applied consistently, fairly, or impartially. Whilst the core groups are not independently advised by lawyers experienced in good safeguarding practice, there is the omnipresence of communications advisors, sometimes more than one. The deepest suspicion of those subjected to this process, and many taking an outside observer’s interest, is that these are bodies that function as quasi-judicial adversarial proceedings without the requisite checks and balances of due process, failing all tests of natural justice, and which prioritise the reputation of the Church above common standards of natural fairness.

This letter is prompted by the processes exposed in three current cases. We do not take a view on the individual merits or outcomes of these, but refer to them as typical, representative indicators of the arbitrariness of how the system malfunctions. These case have revealed the following:

1. There is an absence of a properly constituted appeal or review procedure at any stage of the process. No matter how egregious the failures to abide by the Church’s own rules or basic principles of law and good practice may be, there is no remedy.

2 . There is an absence of a comprehensive conflicts of interest policy and, in its absence, an unwillingness to exercise available discretions in the selection guidance and management of the core group membership, so as to ensure a fair and unbiased process throughout their deliberations. A simple illustration suffices. A legal firm may act as advisors to a Diocese which may ultimately play a part in concluding a case, and may simultaneously act for a complainant, but not a respondent. This is currently happening with no institutional awareness of impropriety or willingness to resolve such blatant conflict of interest. The right to a fair trial and preservation of a degree of “equality of arms” are both observed in the breach.

3. When institutional jurisdiction is in question, the Church asserts jurisdiction, but does not explain its reasoning in matters of complex and obscure law. It is unfair to place responsibility for test-case litigation on an individual when the problem lies with the institution. The decision as to who is, and who is not, within the Church’s jurisdiction appears to be arbitrarily and selectively applied without the principles upon why such distinctions are drawn being convincingly advanced for scrutiny.

4. When there have been breaches of the Church’s own rules designed to ensure procedural fairness, there has been secrecy and reluctance to acknowledge error. Thus, in the Dean Percy case, the absence of proper minute-taking has been obfuscated and glossed over. A core group met on 13 March 2020, but no one was designated as a minute-taker. The complainants have received the ex post facto notes created three months later, whereas the Dean is refused even redacted copies. When a replacement Chair of the core group was appointed, she was the undisclosed professional referee for the Investigator.

5. There has been inconsistency and arbitrariness in the way persons were admitted to or excluded from presence or representation at core groups. Thus, three complainant dons from Christ Church, Oxford (none of them primary victims or witnesses of alleged abuse) attended the Dean Percy core group meeting on 13th March, whereas the victim complainant known as “Graham” was neither invited to attend nor attended the core group considering his complaint against the Archbishop of Canterbury, nor was he told it was being convened. This is perceived as selective and privileged access.

6. Having expended charitable monies on independent reports to make recommendations on safeguarding practice, for the benefit and safety of complainants and respondents alike, and having accepted the recommendations thereof, there has been a longstanding failure to make timely changes by the implementation of rule revision, protocol, or any other practical means to put right the historic failures and malpractices which have continued. Thus, all but one of the recommendations of the 2017 Carlile Review into the Bishop George Bell case were accepted, but not implemented; and the process errors are still replicated at this time in current cases. Lord Carlile has recently opined:

“I do not believe that the Church has got to grips with the fundamental

principles of adversary justice, one of which is that you must disclose the

evidence that you have against someone, and give them an equal opportunity to

be heard as those making the accusation.

“And you cannot give them an equal opportunity if there are conflicts of interest

involved. Anyone with a conflict of interest must leave the deliberations and take

no further part. This is what lawyers understand as the law of apparent bias. It’s

not to say that such people are biased: that’s often misunderstood. It is the

appearance of bias that matters.

“Having people on a core group with a conflict of interest is simply not

sustainable and is, on the face of it, unlawful.

“And to fail to allow the person accused to represent themselves, or be

represented, in the full knowledge of the accusation, is not sustainable, and is,

on the face of it, unlawful.”

7. There is a regime in which partiality, privilege and reputational management have taken precedence over due process and proper standards appropriate to an adversarial quasi-judicial process. Thus, the 84-year-old Lord Carey had his Permission to Officiate (‘PTO’) summarily revoked in June 2020 within days of historic information arising (relating to events over 30 years ago), and the press notified, whereas the newly chosen Archbishop of York retained anonymity from the outset of process until a benign judgement was announced. We take no position on the justice of the outcome but highlight the contrast which brings the Church and its systems into disrepute though a perception of bias and privilege.

8. When unfairness and breaches of principles of natural justice and human rights legislation have been brought to the attention of those charged with the responsibility to manage fair and proper process, there has been a refusal to set aside bad process and a prioritisation of “saving face” rather than a willingness to rectify error and restore proper process.

Any one of the above reasons is serious to those adversely affected by the Church’s longstanding poor practice in this field. Collectively and cumulatively it is a picture of ongoing injustice. The institutional strategy persistently to ignore or deny the serious character of these deficiencies falls well below what is expected of the Established Church, and the failure of Archbishops’ Council to call those with operational responsibility to account represents an important dereliction of trustee duties.

Many of those affected or potentially affected are significantly conflicted. At the recent ‘virtual’ meeting of the General Synod (on 11 July 2020) we learnt that there are 27 extant NST core groups. We understand that they relate to complaints against senior clergy, namely bishops and cathedral deans. Some, undoubtedly, will relate to currently-serving diocesan bishops. Virtually all the CDM complaints against the episcopacy of which we are aware result in “no further action” in the cases of currently serving bishops. Those no longer in office seem less protected. It is probably fair to say that there is a powerful disincentive to speak publicly for reasons of collegiality and self-interest. Those who manage the processes within the administration defend reputation and the retention of the powers they de facto exercise. Yet, those of us who have campaigned for reform are often privately urged to “keep doing what you are doing”.

These problems need resolving and the ongoing replication of the same errors in current cases lead us to the reluctant conclusion that outside intervention is now needed, and so we come from many perspectives, many experiences, and many parts of the Church to ask that you intervene to mandate the Archbishops’ Council of the Church of England to account for its failure to rectify serious errors or manage these processes in the interests of justice towards complainants and respondents alike. The risk of not doing so is that this charity sector as a whole will suffer, and that the egregious failures of safeguarding practice and protocol, with the Archbishops’ Council over the NST, will affect churches and charities across the land, causing further and significant collateral damage.

Yours sincerely,

David Lamming Member of General Synod; Barrister (retired)

Martin Sewell Member of General Synod; Child Protection Solicitor (retired)

Lord Carlile of Berriew CBE, QC

Lord Lexden

His Honour Alan Pardoe QC

Sir Jonathan Phillips KCB

Prof Sir Iain Torrance President Emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary KCVO, Kt

Prof Nigel Biggar Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology, University of Oxford

Prof Linda Woodhead Lancaster University; contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’

Revd Jonathan Aitken

David Pearson Founder of thirtyone:eight – Christian Safeguarding Charity

Mike Hames Former Detective Superintendent and Head of the Paedophile Unit at Scotland Yard

Gilo Co-editor of ‘Letters to a Broken Church’ ; IICSA core participant; ‘victim of the NST’

Christina Rees CBE Contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’; member of General Synod 1990-2015; founding member of the Archbishops’ Council

Andrew Carey ‘Victim of the NST’

Dr Ruth Hildebrandt Historian and freelance writer

Grayson

David Mason Former Assistant Diocesan Secretary, Lincoln and Governance and Administration Manager, Chichester

Lizzie Taylor

Prof John Charmley Pro Vice-Chancellor Academic Strategy & Research, St Mary’s University

Revd Simon Talbott Member of General Synod

‘A Survivor’ Survivor of sexual assaults by the Revd Meirion Griffiths

Richard Scorer Head of Abuse Law, Slater & Gordon, solicitors; contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’

Revd Valerie Plumb Member of General Synod

Rt Revd Alan Wilson Bishop of Buckingham; contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’

Graham Sawyer ‘Victim of Peter Ball, the NST and the Church Establishment’

Revd Stephen Heard

Simon Barrow Director of ‘Ekklesia’

Revd Stephen Trott Member of General Synod

Revd Paul Benfield Member of General Synod; synodal secretary of the Convocation of York

Margery Roberts Secretary of the Society of the Faith

Revd Canon Angela Tilby Canon Emeritus of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

Julian Whiting ‘Victim of the NST’

Simon Sarmiento Editor, ‘Thinking Anglicans’ blog

Rev. Janet Fife, survivor of Rev. X and the NST’.

‘Graham’ Iwerne Trust/John Smyth survivor; ‘victim of the NST’

Andrew Chandler Professor of Modern History at Chichester University; Biographer of Bishop George Bell.

Revd Canon Rosie Harper Member of General Synod; contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’; Co-author of ‘To Heal not to Hurt’

Dr Janet Lord Bishop Whitsey and NST survivor; contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’

Rev. Mark Carey, respondent, and victim of the NST’.

Revd Dr WS Monkhouse

Revd Matt Ineson Victim of the Revd Trevor Devamanikkam, CofE bishops and the NST

Revd Nathan Ward

Revd Stephen Parsons Editor, ‘Surviving Church’ blog

Kathryn Tucker Member of General Synod

IICSA core participant Victim of Bishop Peter Ball and the NST

‘AN 87’

Tina Ney Member of General Synod

Andy Morse Victim of Iwerne Trust/John Smyth QC

Revd Peter Ould

Dr Josephine Anne Stein Contributor to ‘Letters to a Broken Church’

Dr Tom Keighley, Clergy victim of the NST PhD, FRCN

April Alexander Member of General Synod

Dr Adrian Hilton Chairman of the Academic Council, the Margaret Thatcher Centre

Jane Chevous Survivor of clergy abuse by two bishops; founder of ‘Survivors Voices’ – survivor-led peer support

Dr Gavin Ashenden Former chaplain to HM The Queen; now supporting victims of abuse and maladministration

Very Revd Michael Sadgrove Dean Emeritus of Durham Cathedral

Philip French Member of General Synod

Kate Andreyev Clergy wife

Revd Andrew Foreshaw-Cain Chaplain, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

Revd Dr Carrie Pemberton Senior Fellow, Ethics and Public Life,-Ford Margaret Beaufort Institute of Theology

David Greenwood Head of Child Abuse Compensation Team, Switalskis Solicitors

Janet Garnon-Williams CPS prosecutor (retired)

Richard Symonds The Bell Society

Revd Canon Dr Robin Gibbons Ecumenical Canon, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

Sue Atkinson Writer; survivor; member of ‘Survivors’ Voice’

Rt Revd David Atkinson Assistant Bishop in the Diocese of Southwark; supporter of ‘Survivors’ Voice’

John Tasker Lay Worker in the Church of England

Dr Peter Owen Member of the Church of England

A Survivor ‘A survivor of Diocese of Chichester abuse