by Gilo

Having written a piece about the use of ‘core groups’ and the Clergy Discipline Measure, to be discussed by the House of Bishops this month, Surviving Church has received a further contribution on the topic from Gilo. Gilo’s current piece focuses on the Martyn Percy saga at Christ Church Oxford and explores the way that Church of England official safeguarding procedures have somehow become entangled in the affair. The process has become messy and it is hard to see a good outcome when good practice and the pursuit of fairness appear to have been bypassed along the way. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the entire structure of Church of England safeguarding is on trial in this one case. And yet the situation presents to survivors a new opportunity to bring legitimate complaints about many serving bishops. In the past, complaints have been routinely dismissed, but now we would expect to see core groups and action. Ed.

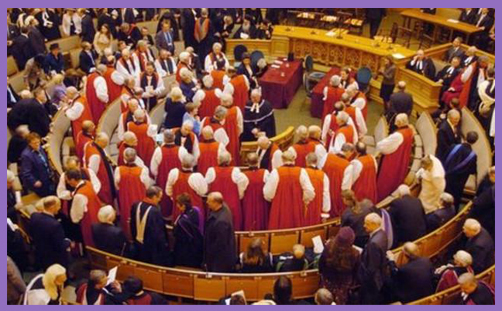

The National Safeguarding Team has instigated a ‘core group’ to investigate complaints against Professor Martyn Percy by disaffected members of Christ Church alleging safeguarding failures. This follows the comprehensive dismissal by Sir Andrew Smith (a retired High Court judge) of the original case brought against Percy by members of the Governing Body seeking his removal from office. To many who have followed the media stories on this saga, this latest development resembles a kangaroo court with the deployment of weaponised safeguarding in a desperate attempt to oust the Dean. It was reported by the Church Times (29 May) that Percy has no representation on this core group but must adhere to its diktat. It seems likely that this action by the NST will add considerably to the reputational damage already done Percy by the group of college dons.

As has been previously written on this blog and elsewhere – NST core groups are already a deeply contentious issue. There’s a striking parallel here with they way they’ve been used in survivors’ cases as little more than a PR management exercise. In my case, the NST had the lawyer present who led the settlement for Ecclesiastical Insurance – but I had no representation and didn’t know a core group had taken place for 18 months. The appropriation of the NST in Percy’s situation is likely to rebound heavily on an already mistrusted and discredited Church of England national safeguarding.

It has been reported that two of the dons pitched against Percy sit on this core group. If either of them sent or received proposals to “poison” the Dean and fish his “wrinkly withered little body” out of the river, then the NST has entered the realm of Ortonesque farce. In most organisations emails at this level of delinquency about a colleague, and circulated widely amongst a professional body, would result in disciplinary action. Survivors have frequently written angry letters to and about bishops – I openly include myself in their number but have never expressed a wish to see particular Bishops fished out of the Thames from Lambeth Bridge! The media reported that the Senior Censor tried hurriedly to get the College Council to self-delete the full report in what appeared to be an attempt to bury these juvenile emails. The Senior Censor apparently sits on this core group. You couldn’t make it up!

But more disturbingly, I have heard on good authority and am aware that others have also heard, that at a recent Governing Board of the college, one of the senior college figures boasted to the Trustees “the wily Censors have made sure they complained to the right part of the National Safeguarding Team”. If true, both ends of that statement are extraordinary. I don’t know if the NST are aware of this. I don’t imagine so. There would be an outcry across the Church if the NST had been complicit in their own ugly appropriation. It would raise questions about who is controlling different bits of this structure, and in particular who is pulling the strings of the “right part” of the National Safeguarding Team. I suspect Synod members would throw their hands up in horror and ask: how the hell does one rescue a Church’s national safeguarding so far down a road of ethical dysfunctionality?

But this core group sets an interesting precedent. Quite a few Church of England Bishops have been accused of safeguarding failings, cover up, poor response or no response towards survivors, gaslighting, blanking and fogging, dishonesty – yet how many have had core groups convened about them by the National Safeguarding Team? It would now seem that a complaint from a single source against a senior church officer is no longer time-limited, but will result in the formation of a core group on which the complainant can be personally represented. The person under investigation will presumably be asked to step aside from safeguarding responsibilities during the investigation. Although the circumstances in which this has come about are ugly and point to church officialdom targeting a well-known critic – the situation has unexpected potential for survivors. There are a significant number of survivors who have credible and legitimate claims that serving bishops have mishandled disclosures of abuse or have been dishonest in their response. We might welcome the opportunity to have core groups established, and to have complaints acted upon at last. I suspect the number of bishops who could feasibly be asked to stand down through such action might be surprising.

There are bishops on the National Safeguarding Steering Group (NSSG) who in mine and others view shouldn’t be on that group until retraining, moral reorientation and proper apologies render them fit to respond to survivors with honesty, decency, compassion and a sense of urgency to situations. The same could be said for other bishops. Matt Ineson could justifiably bring legitimate complaints against four bishops and one retiring archbishop. If the NST were to follow the same route as they have done with the Dean of Christ Church – all five would be required to abide to the conditions imposed by the core group while those investigations take place. And Matt Ineson would have representation on each of the core groups, or one combined core group, and could be present himself presumably if he so wished. And that is only one such situation. There are plenty of others. Incidentally the CDM complaint against the Bishop of Lincoln is also proceeding out of time, which again raises questions in relation to CDM complaints made against other bishops – all of which were ruled out of time. It would seem sensible to find out from the Director of Safeguarding what the formal route now is for complaints to be made, so that several bishops can be asked to stand aside without further delay while core groups are set up. The NST can hardly ignore any such request. Survivors might speculate as to which part of the NST is the “right part” to complain to for action. If, for example, you send an email to safeguarding@churchofengland.org, does that go to the right part, or the wrong part?

Returning to Martyn Percy who I know a little, he wrote a chapter for Letters to a Broken Church and has been an unwavering ally for survivors. My personal view is that he has more integrity and courage than many current bishops whose response to the abuse crisis (with a few notable exceptions) has shown them to be a run-for-hills culture … insipid at best, downright dishonest at worst. I end with a quote from his chapter in our book:

Like many loyal servants of the Church of England, I have watched IICSA over the past three weeks with a growing, troubling, deep sense of shame. This is a hard thing to admit. To know that you belong to a body where you can no longer believe of trust the account of the polity or practice that is being offered in defence of its behaviours by its own leaders. To know that the real victims in this tragic farce who are still waiting for basic, fundamental rights that should be givens for the church – recognition, remorse, repentance – are abused twice over.

In the first instance, it is by their actual abuser. The second time, and far worse, is the subsequent abuse perpetrated by the Church. For this is a church that is deaf, dumb and blind – and seemingly wilfully indifferent to the suffering undergone by those abused – and then addresses this with little more than an incompetent veneer of safeguarding practice, which only further compounds the original act of abuse.