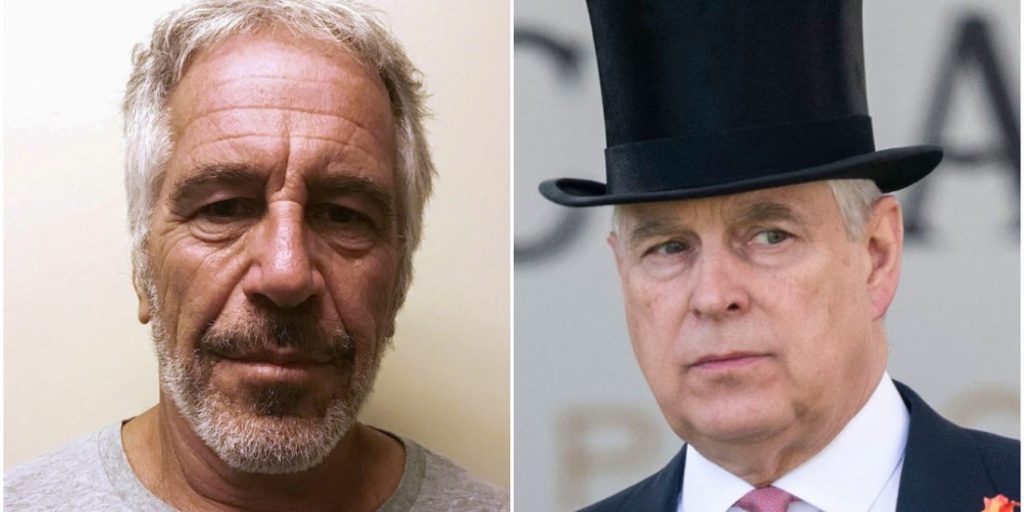

I made a decision that I would not allow my equilibrium to be disturbed by watching what many have now called the ‘car-crash’ interview of Prince Andrew last Saturday. And yet even without watching the Newsnight programme, I have drawn out, from the extensive commentary, some telling parallels with the safeguarding scandals of the Church and elsewhere. The question of whether Andrew ever met the woman he is accused of having sex with is not the central issue at one level. As with the many cases of sexual abuse in the Church of England, it is just one event in the miasma of numerous half-truths, denials and examples of cruel behaviour. How many times have we heard in various contexts the denial which comes in the form of ‘I have no recollection’ when abusers or colluders are faced with claims of abuse? Such forgetfulness does not impress an observer or here, a television viewer. It does have the advantage of being an answer that allows no follow-up question. A protestation of ‘I don’t remember’ will always close down that part of the interview. Perhaps that is why such a response was fed into the interview by Andrew’s publicity machine.

The most important part of the interview seems to have been what was not discussed. Andrew mentioned sleepless nights of self-recrimination for not being more careful in his friendship with Epstein. Having had nine years to think about this friendship after the full horror of Epstein’s behaviour had come out into the open, you might wonder why Andrew has never given any thought to the victims. The focus in his mind was on the damage to himself, his family and the institution that he represented. In other words, the victims/survivors of Epstein’s behaviour never entered into the royal awareness. He certainly had nothing in the way of regret or sympathy for their situation.

There are a number of words that seem to be appropriate in describing Andrew’s attitude. The words might include elitism, arrogance, failure of empathy and a deficit of imagination. If we are really to believe that Andrew saw nothing odd about the clusters of very young girls in the various mansions where Epstein entertained his guests, this suggests a chronic naivety and blindness. In short, Andrew felt himself to be too important to notice such details. Other people were apparently there to amuse him, buy him drinks and generally provide for his needs. From a psychological point of view, we are observing chronic narcissistic behaviour. The individual sees himself at the centre; other people are there to be used and tolerated while they can provide gratification. Being royal allowed Andrew to offer one thing in return, his momentary royal attention. For some people, mesmerised by the institution of royalty, two or three words from such an Important Person can boost a flagging ego for a long time.

Why do I link the Church’s safeguarding crisis with Andrew’s poor interview performance? It is because I see many sad parallels. In Andrew’s interview there was the effective air-brushing away of the suffering of many hundreds of innocent victims. His claim was that he was not a perpetrator at any point could possibly be true, but, by failing ever to speak up for the girls, we saw how to him such individuals had no value and were beneath his princely attention. No doubt he wished, as Epstein would have done, the complaints of the victims to be shut down and silenced. The way the Church has often failed to acknowledge victims and allow them an honourable place in its corporate consciousness seems to be a similar phenomenon. Every time a Bishop ‘forgets’ a disclosure of abuse or a church leader helps to cover up decades of abuse, it is eerily close to Andrew omitting to mention anything about the victims of his friend Epstein.

One issue that my blog has given a possibly disproportionate amount of time to is the Smyth/Fletcher affair. Events from so long ago might in other settings lose some of their potency after 30 plus years. But to repeat, the safeguarding crises in the Churches have never been only or even mainly about the abusive events of the past. It is about the cover-ups that have followed. People who watched the Andrew interview on Saturday are rightly alarmed at the accusations levelled against the prince. But they are probably just as alarmed by the twists and turns of his publicity machine as it has tried to help extricate him from his appalling choices. What is especially damaging about the Andrew affair is his persistent refusal to own up properly to what happened in the past. However ghastly and unroyal, a clean breast of the behaviour of a younger man might just have earned public forgiveness. The denials and unconvincing story lines invented by public relations experts have done the opposite. It is hard to see how Andrew will ever live down what passed in the interview on Saturday night.

The effective demise of Prince Andrew as a public figure may have begun last Saturday. A similar process may be in operation in the Church of England as well. Here the ‘car-crash’ has not yet happened but there are many signs that people in and outside the Church are becoming weary of the spin and cover-up that seems endemic in parts of the Church. The church body as a whole may seem healthy with the founding of new congregations and signs of growth in various parts of the institution. But readers of this blog will know what I am talking about when I say that there are areas of serious disease within the body. Since the safeguarding crisis has become public knowledge, it has become more and more apparent that many, if not the majority, of our church leaders have been complicit in suppressing information about the past. What information is publicly available has in every case come from survivors and the work of investigative journalism. Channel 4 broke the Smyth episode and the Daily Telegraph came up with the outlines of a story about the activities of Jonathan Fletcher. That process will not stop.

The hierarchy of the Church of England are clearly aware of the full dimensions of all the hidden scandals and many of them are fearful of more press disclosures. One particular group that has more to fear than most are the network of conservative leaders that form part of the Renew Constituency. Numerically this group is not large, but over the years they have presided over many of the institutions with the darkest secrets. It is possible to speak of Iwerne/Renew/Church Society/AMiE together with a cluster of massively wealthy parishes, such as St Helen’s Bishopsgate, as a single entity. Following the closure of REFORM and the re-organisation of the other groups into the Renew network, the Vicar of St Helen’s Bishopsgate, William Taylor, has become the most powerful figure in this group. He and Hugh Palmer, the Rector of All Souls Langham Place have together been working within the conservative networks for many decades. It is not unreasonable to conclude that their current silence and irregular approach to safeguarding (the curious messages sent out to churches after the Fletcher scandal broke) are consonant with an extensive knowledge of the shameful things that have gone on in the past. If these leaders were truly innocent of any information about the Smyth/Fletcher outrages, you would expect their churches to be at the forefront in offering massive help to those in their constituency who have been affected. Instead appeals for pastoral support there seem to meet with a patrician silence. As with Prince Andrew, survivors are apparently too unimportant to care about.

Prince Andrew has shown to the world that his first concern, in his blinkered view of the world, is to himself and the institution of the Royal Family that he so poorly represents. The Church in its lamentable history of care for its own victims has also shown a blindness to anything but its own reputation and the survival of the institution. The failure to come clean about the past is enormously damaging. The eventual realisation by ordinary people of what has been hidden from them by people they had always looked up to in respect will cause a shocking sense of betrayal and disillusionment which will reverberate for decades to come.