Motto: We’re On Some Sort of Journey

Owner: William Nye Esq.

by Anon.

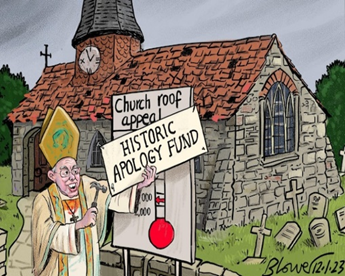

A Statement from CofE-Air: Proud Sponsor of Lambeth Palace FC

In recent months, it has been suggested that Church of England Airways—better known as CofE-Air—has enjoyed a less-than-stellar safeguarding record. This is wholly unfounded. But it is apparently impacting Lambeth Palace FC, who recently parted company with their Head Coach, Justin Welby, after a very poor run (Ed: surely several seasons?) of results.

CofE-Air wishes to make the following points concerning all the intense, undeserved, ill-informed and very unfair media scrutiny endured, and a handful of baseless complaints from a few of our passengers who claim to have had a less than satisfactory experience of journeying with us. In our statement, which will not be subject to media questions or further comment from us, CofE-Air reminds the public, passengers and its Purple Clubcard members that:

- We take our passengers’ and customers’ comfort and safety very seriously. Safeguarding everyone who journeys with us is, front and centre, our number one priority. Safeguarding is what CofE-Air is all about, and we aim to deliver a service like no other.

2. We offer an elite high-cost low-budget safeguarding service for everyone. We avoid additional costs being passed onto our customers by making sure that our pilots, ground crew, cabin crew and other staff are unregulated, unlicensed and unaccountable to any industry standard.

3. We keep our published budget lower still by using lots of unpaid volunteers to oversee safeguarding, check-ins, etc. This ensures that all passengers are responsible for each other at all times, as safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility, not just the pilot(s) and crew.

4. In the unlikely event of any emergency procedures being required onboard one of our journeys, customers should be aware that all our staff have had crash-awareness training to the basic minimum standard. This means that when a crash does actually happen, the staff should know that there has been a crash and will be able to confirm that. They are fully trained to be aware of crashes.

5. In the unlikely event of a serious accident, Purple Clubcard members must sit facing forward in business class and first class, and should not on any account look backwards or attempt to intervene on behalf of those seated in economy class, who will be supported by our volunteer crew.

6. For the avoidance of doubt, Purple Clubcard members seated in first and business class must on no account respond to any cries for help or demands for assistance from economy class passengers. The volunteer crews will distribute forms to fill in for all those in distress, sometimes whilst the emergency is actually taking place. Obviously, Purple Clubcard members should never speak to the media about a serious incident.

7. Delays in reviews, journeys and transit are never, ever our fault and are frequently caused by troublesome passengers making annoying complaints about poor standards, lack of regulation, too much money being spent on PR, lawyers, advertising and marketing, and not enough on passenger safety. This only adds to our costs and causes further delays on journeys. If only passengers would shut up and stop complaining, we might be able to run an uninterrupted service for once.

8. We do not offer independently assessed compensation, assistance, or redress schemes to any passengers injured through our service or suffering delays (including fatalities) attributed to our provision. To do so would increase our costs. All our independent arbitration and mediation schemes are run in-house by trusted third parties who meet Mr. Nye’s criteria for CofE-Air independence.

9. In the unlikely event that you might have encountered a below-par experience with our service, or had a safeguarding issue unresolved, our website publishes details of how to complain. The complaints hotline is monitored on a monthly basis (we spin the bottle to select a random number between 1-31 for the day the ‘phone is answered). There is an unmonitored email address to write to, and you can also write to us at the designated PO Box 1662, Vennells Court, London – where , again that box is emptied one Sunday per month in Ordinary Time.

10. If you have a complaint that does not fit our criteria, then we do not undertake to consider your grievance. The policy on non-standard complaints and grievances is available upon request from Mr. Nye’s personal office, but is not published. But you can always write and ask.

11. In the event of a possible inflight accident, or more likely, an on-ground collision, and more likely still a failure to take off at all, or there being no means of embarking on the journey whatsoever, all passengers must assume the CofE-Air brace position.

12. In the front pocket of your seat you will find the brace position described in detail: tense up, put on a rictus grin, say nothing to the media, and pretend that whatever happens next, it was all planned and will be OK anyway. Familiarise yourself with the aisles and exits. Look after yourself first before you look after anyone else. Run. Do not look back.

13. However, please ensure that Purple Clubcard members have already disembarked and are taking refreshments in the complementary lounges before you even think of moving. Church on Sundays is the kind of place where clergy preach on “the first shall be last and the last shall be first.” This does not apply here.

14. Remember that safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility, and you may be financially liable for any claims made against CofE-Air. We employ nobody to any industry standard, and when a crash or accident happens, the volunteers and passengers are usually culpable. Purple Clubcard members are naturally indemnified.

15. We do not carry life jackets, whistleblowing equipment or lights on our journeys. These might be industry standard, but CofE-Air is not subject to the law in the same way, so this allows us to keep our fares high, competing with the most expensive, yet operating on low-cost budgets.

16. Pilots and paid crew who might accidentally or deliberately fail in safeguarding duties are subject to our strict and rigorous internal disciplinary procedures. An indication of how safe CofE-Air actually is can be gleaned from the very few pilots who are ever grounded, suspended or subjected to any meaningful disciplinary action.

17. However, volunteer ground crew and non-essential low-profile staff often make the most egregious safeguarding mistakes. We aim to punish these individuals with the full force of our disciplinary code. (Let them be an example to us all, and a sign of how seriously we take our PR).

18. Re-branding. In the event of an established safeguarding position or role becoming completely untenable, CofE-Air reserves the right to keep that person in post doing exactly the same job to the same standard as before but rename the position and role so as to give the impression that it will all be different from now on. It won’t be.

19. We remain resolutely opposed to adopting any normal industry standards, as that might adversely impact on the control, cost, quality and reputation of our service.

20. At all times remember that CofE-Air puts safeguarding at the front and centre of its concerns, and that is why the very best people to conduct Fatal Accident Inquiries, Performance Reviews, Critical Incident Reports, Lessons Learned Assessments and Retrospective Analyses are hand-picked by the owner of CofE-Air, and also the Chairman and Owner of Lambeth Palace FC, Mr. William Nye. As on the football field, so in the journeys undertaken with CofE-Air. You only get the results that he is prepared to commission and underwrite. All other results are wrong, and will be treated as such.

21. We do run a bus service – but only for throwing people under who can be made to take the blame for our failures. Please note, this is not a Replacement Bus Service. Our buses do not connect destinations or have any other purpose other than to emphasise our zero-tolerance policy towards any failure to keep up appearances.

22. In the event of your journey being delayed, sit down and wait for the announcements in the departure or arrivals concourses. Or just go home. Whichever is quicker. Maybe go home?

23. In the event of an accident, unfortunate death or other injuries, we also ensure that all of our Lessons Learned Reviews are delivered in a timely manner to ensure that the reputation of our safeguarding is safeguarded, and customer confidence is maintained by:

- Running the clock down.

- Redacting embarrassing evidence and facts, and named individuals (only those we might need to protect) in order to save face.

- Ensuring nobody can remember what the original problem was.

- Delaying publication – over five years late remains the Gold Standard.

- Enabling the guilty to retire in peace without being impeached.

- Reducing the possibility of bad publicity.

That way, the public may never suspect for a moment that any of this service to passengers is carried out by unregulated, unlicensed, unaccountable and non-standard personnel and that there is no independent regulator to appeal to when things are going very badly wrong.

The Lead Bishop for CofE-Air stated:

“Whilst it is true that I, and indeed all of my predecessors, have no externally-validated qualifications in safeguarding whatsoever, or undertaken any industry-standard eternally-recognised training outside CofE-Air, and have no transferable skills or expertise that another carrier could ever deploy, valued customers and passengers on any and all CofE-Air journeys should nonetheless be reassured by the uniqueness of our standards which speak for themselves.”

A spokesperson for the safeguarding carrier industry said:

“CofE-Air are completely unregulated, unlicensed and wholly unaccountable to any normal industry standards of health and safety, and operate outside basic legal oversight. CofE-Air’s record is utterly atrocious, falling well below the minimum standards for any provider. If you do travel with them, you will have no rights, and no recourse in the courts if things go wrong, which they usually do. You travel with them entirely at your own risk, and in so doing will be taking your life in your own hands. Or putting your life in their hands. We strongly recommend you do not undertake any journey with them. Ever.”