by Fiona Gardner

‘It is a helpful resource, which will be added to, but also a challenge to us all @churchofengland to continue to do better.’

So writes Stephen Cottrell, Archbishop of York on the House of Survivors website. I couldn’t agree more … but after all this time it isn’t only a challenge but also an imperative ‘to do better’, because Stephen Cottrell is talking about a deeply embedded culture of institutional betrayal, a betrayal that compounds the original abuse and trauma. What both House of Survivors and Surviving Church do is highlight example after example of this. Over the years the institutional church has tended to emphasise individual situations, as if they were isolated incidents from which particular lessons can be learned. What gathering all the data together shows is that the problem is systemic, and the institutional betrayal partly occurs because reputation is valued over the well-being of the members, and issues of power and control dominate.

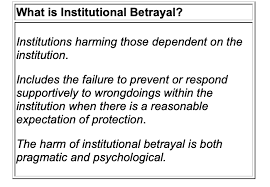

Institutional betrayal as a concept has been around for a while, and is the term used when an institution causes harm to an individual who trusts and has been encouraged to depend upon that institution. Betrayals are violations of trust and dependency perpetrated by the institution. There’s another interesting concept about the ‘organisation-in-the-mind’ – in this context this is about the idea of church, how we think and imagine the church, so it becomes a bit of constructed social reality – this is not to do with the buildings, or services, or activities. The church-in-the-mind will clearly differ: for example, the church is a sacred and safe place full of people who are kind and compassionate, and I will be welcomed. Or, the church is a place of judgement and bigotry where I won’t fit in. Generally, though, assumptions of trust, safety and dependency are implicitly encouraged by the whole church culture and by the hierarchy.

Therefore, for the survivor of clergy abuse there is a double betrayal by the institution: the first is the original criminal abusive act from someone in a position of trust; the second is the inadequate and re-traumatising response by the member of the church hierarchy who has heard the disclosure. This is secondary victimization. The painful part is that when someone reaches out for help after abuse, they are already placing a great deal of trust in the system as they risk disbelief, blame and refusals of help. To report the abuse brings the conflict of potentially losing the sense of belonging within church community, but to not report risks the abuse continuing and a denial of the traumatic reality.

The concept of institutional betrayal arises from betrayal trauma theory, that traumas perpetrated within a previously trusted and dependent relationship are remembered and processed differently to other traumas. Research shows that the impact of institutional betrayal includes further psychological distress, anxiety, dissociation, etc. If re-traumatisation occurs through institutional betrayal the original trauma is compounded, and so once again the victim’s mind is overwhelmed with more than it can make sense of and manage. The organization that encouraged trust and dependency is revealed to be careless, unconcerned or more actively destructive. Betrayal blindness may sometimes be displayed by all involved in order to preserve relationships, institutions, and social systems upon which they depend. In other words, institutional betrayal may be minimised not only by the church hierarchy (for example saying – that was then and now it is different, or we must continue to do better), but also sometimes by the victim who defends against the reality by remaining hopeful that their needs may still be recognised and met.

Whilst it may appear that an experience of institutional betrayal is less visible, it is not less injurious than the original abuse. It’s all about the social dimension of trauma, independent of the individual’s reaction to the event, and the way events are processed and remembered is related to the degree to which the traumatic event represents a betrayal by a trusted, needed other, and this is whether it is an individual or institution – or as in many situations both. Institutional betrayal by the church on top of an original abusive act is a kind of breakdown of the organisation-in-the-mind. It is a massive attack on an established way of going about one’s life, of established beliefs about the predictability of the world, of established mental structures.

Institutional betrayal can happen through acts of commission in which the institution takes action that harms its members, for example by actively protecting an abuser. It can also betray through acts of omission, in which the organization fails to take actions that could protect members, for example taking no appropriate action and ignoring guidelines.

Here’s an example of institutional betrayal that includes both commission and omission:

On May 20 2022, a letter was published in The Church Times by “Graham” about the Church of England’s continued and chronic lack of response to the serious abuse carried out by the late John Smyth QC. Thanks to Andrew Graystone’s research, we know that the lengthy suppression of information and accountability is complex. The abuse was known about since 1982, the perpetrator protected, and victims unheard and denied justice (acts of commission). As Stephen wrote on this website in March 16, 2020:

Many individuals were part of the story, not just as bystanders, but sometimes as active colluders. … There were many high up in the network who knew what was going on. The failure of a single one to come forward, suggests that the word conspiracy is an accurate one to describe this corporate behaviour.

In May 20 2021, nine years after being told of the abuse, the Archbishop of Canterbury met with some of the victims, and promised investigations would take place into those who colluded with the cover-up. In his letter “Graham”, a year later, writes:

As a victim, I regard the archbishop’s words as appearing to be just hot air: promises unfulfilled. Has he “kept in touch” with these investigations, as he claimed he did in 2013? Or has he just assumed that someone else is dealing with it, which he described at IICSA as “not an acceptable human response, let alone a leadership response”.

Justin Welby responded in The Church Times on the June 10 2022 stating, that delays to both the Church-led and independent investigations were unintentional and being followed up (acts of omission).

Here are the usual dynamics of deception that appear to have underpinned the way that the institutional church has systemically betrayed survivors and their supporters. As with “Graham”, many of the abused remain victims (in his case ten years after he publicly disclosed), victims not only of the original crime, but also victims of emotional and spiritual abuse from the church’s inadequate and neglectful response: victims also of institutional betrayal.

The sheer neglect and lack of validation shown by this example mirrors the deep lack of validation by the perpetrator, and clearly compounds the damage. Justin Welby illustrates a process of cognitive re-framing to turn the destructive non-responding into somehow being morally acceptable by employing the defensive manoeuvres that it was ‘unintentional’ – what does that mean? Perhaps he is displacing and projecting the responsibility onto someone else, or another part of the system. Similar to the behaviour of some perpetrators the methods involving such acts of omission usually include obfuscation, rationalisation and denial. It also suggests an element of sadism, where the aim is (no matter how many years it takes) perversely to oppose and thwart and to obstruct. The above example, as with other betrayals, is undeniably to halt the course of events, to favour inertia – and, as in abuse to rub out and negate the wishes of the other person.

Andrew Graystone in Falling Among Thieves notes that the centripetal power of orthodoxy has meant that whatever is done to address issues of abuse in the church has been done without changing anything substantive in its culture, practice, or theology. Consequently, much is done, but little changes – lofty statements are made, but to no effect. This is because change can only emerge when the current situation is honestly faced. Abusive cycles of institutional betrayal are hard to break, and to do so requires motivation and energy. To not do so is to embrace apathy and group laziness as an avoidance of acknowledging self-deception and the reality. The institutional church is still stuck in a collusive refusal to know or to pursue and examine the truth that certain destructive traits have dominated actions. Inept and inhumane responses damage, and those who are damaged have seriously suffered, but the damage has also been to the system. Betrayal – a central theme in the Passion narrative, and now a central theme in the institutional response to abuse gets re-enacted systemically again and again. The hope then lies in organizational redemption which demands authenticity, humility to take on constructive criticism, and astute integrity with soul-searching at the very top of the church hierarchy. Organizational redemption corrects the past wrongs of institutional betrayal, a debt is repaid, and hope restored.

One of my Conservative Evangelical allies has put his finger very clearly on the key problem here.

What we are seeing is a culture which has learned and benefitted from a structure of evolved helplessness. Everyone you challenge insists they have no power; Archbishops, the Lead Bishop for Safeguarding , his Assistants , the Independent Safeguarding Board – all deny a capacity to intervene. Hands are wrung, ” thoughts and prayers” offered, a meaningless lessons learned review might occur to no effect, but above all, nobody is ever meaningfully held to account.

A simple truth is this: nothing will guarantee the repetition of bad practice better than the absolute certainty amongst senior Clergy Bishops and Archbishops that they will never be called meaningfully to account for their misdeeds and negligence.

In what other context would this appalling state of affairs be considered remotely acceptable?

I know I’ve been guilty in the past of talking about the C of E as if it were a single entity, whereas it appears to be a loose association of separate entities. In legal form there may be various levels of jurisdiction between parishes and dioceses etc, but in substance there appears to be a great deal of autonomy. You can do almost what you like.

Moreover, a financially strong church stream, such as the HTB axis can have its own autonomy and additional amounts of influence. Rank of bishop is trumped by rank of HTB trustee.

I’ve probably said this before, but I believe the somewhat diffuse structure of the C of E is deliberately in place to disable accountability and minimise group liability.

In the commercial world an organisation will often be structured into numerous limited liability entities. If one fails, the others are not pulled down. There can also be tax advantages.

An institution like Macdonald’s is structured with a franchise model. Individual owners pay to share the brand (and a steady stream of loyal customers) in return for obsessively strict quality control. A Big Mac must be, and taste the same, anywhere in the world.

In the C of E there is a brand. I few years ago I started noticing its logo appearing on schools (where applicable) and local church notice boards. Maybe this helped them, I’m not sure. Public perception of quality control cannot be very high, with a steady stream of abuse scandals hitting the mainstream and social media.

Presumably there are still strong incentives to remain within the C of E, such as continuing clergy membership of probably the most generous pension scheme still open. In private business these defined benefit schemes have long gone.

There doesn’t seem any particular incentive for senior people to want to change the status quo. Moreover the system appears structured carefully to put considerable obstacles in their way, in the unlikely event that they did chose to improve things for survivors.

Expect the trauma to continue and the re-traumatising.

Mention of restitution brings up a question I have asked before. When too much time has passed to correct a wrong, what does restitution look like then? It always gives rise to the person you are talking to saying they cannot change the past. Obviously. That is always true. So is restitution never possible?

The idea that institutions are the problem finds it’s roots in Marxism – blame the constructs, the organisations; but Christian theology says human beings are the problem; we are the ones whose hearts are “deceitful and desperately wicked” according to Jeremiah, and “Out of the heart of man comes evil thoughts…” said Jesus.

Blame shifting began in the Garden of Eden; the way for institutions to survive is to blame anything but the people who run them.

If you are in charge and are responsible for the appointment and overseeing the performance of your employees, and they mess up because of inadequate training or supervision, or do not comply with established policy and polity and agreed rules, they have to be held to account, as should the person in charge.

It’s time to stop passing the buck and face up to the fact human beings are the problem and they need to tell the truth, not hide it, and proper transparent accountability be the norm.

Institutions are only as good or bad as the people who are in them.

Additionally, it is human beings who are responsible for abuse, and need to be held to account. The Church has never been one that supervises it’s clergy – we are “free agents accountable to God” as office holders, dioceses can’t be blamed for the behaviour of individual clergy unless they know that there are issues in that person’s ministry and life which have been highlighted and have failed to act. The institutional abuse and complete failure to support victims are that the institution has no mechanisms for this; pastoral care has always been at parish level, so if there is someone in need, it has to be at parish level that support is organised and given – bishops and archbishops can’t do it, but manifestly have failed to think through how support can be given to trauma victims.

The failure lies in that area – everyone leaves it to someone, which could be anyone but turns out to be no-one. Lack of joined up thinking..

But see the letters to the 7 churches in Revelation 1-3 (long pre-dating Marx). Churches in 7 different cities or areas are addressed as a body each having specific characteristics – some good, some bad. The collected individuals in those churches form a unit which has its own personality and is greater than the parts which compose it.

The principalities and powers mentioned elsewhere also refer to structures which are capable of good or evil.

I have sympathy with this view; we do indeed own our individual contributions to personal and corporate sin. However, when an institution effectively institutionally insulates its senior leadership from being held to account for serious wrongdoing it ceases to be an agent of moral leadership.

It’s a fair point about individual responsibility, but more powerful – as Steve points out – is the collective culture of any large group. Wilfred Bion (covered in earlier posts on SC) made a study of the Church and understood that the basic assumption was one of dependency – because throughout the organisation the institutional church is characterized by a culture of subordination and unquestioning obedience to authority, formal leader(s) is seen as having all the answers, and is expected to take care of the group and make them feel good.

Now it seems like a culture of failed dependency, but still the old structures based on deference to group think hold firm. That’s why it is so hard ‘taking on’ the culture from the inside – it ultimately (as I know to my cost) ends in self-defeat/exhaustion. It is why for so many survivors it is also a forlorn hope trying to remedy past wrongs from the outside. Whatever else the optics of the bishops’ photocall show this is a closed and defended system …

I agree

This piece resonates deeply with me. Walking away from the CofE has very much felt like leaving an abusive relationship. They continued to insist that they cared about me and had my best interests at heart while ignoring the abuse I was reporting. Coupled with the ability to take away my job and vocation, there was a manipulative undercurrent of control. Betrayal is very much the right word to use. Also, to my mind, betrayal of core Christian values which the church is meant to embody. When an impersonal institution is put above people and their families something has gone very, very wrong.

Church-in-the-mind is an important concept to understand, because it helps to explain the devastating consequences for us when things go wrong. It’s a mental construct, a dream of church or a vision of what could be, and it’s held deeply in our minds as a basis of how we think and plan our lives on an everyday basis.

Starting even and especially as a young child, we are aware of being taken to church and Sunday school, and what we thought of it. As is usual in our development we are obliged mentally to construct something to make sense of our lives which we cannot yet possibly know for ourselves. We take on board what others say: our parents, teachers, etc. “church is good, is where good people go, God is good, will make you happy, if…”.

Organisation-in-the-mind is a powerful concept not just for church, but for other organisations we may aspire to be part of, such as schools, places of work, clubs etc. Understanding this thinking can cross-inform understanding of church membership.

The key for me is aspiration. At one time I aspired to join the biggest consultancy firm in the world in my field. I imagined everything about it to be better than pretty much anything I’d experienced so far. To my surprise I was offered a job there one day, despite earlier rejections at more junior levels. And I knew it would be difficult, demanding to work there.

Arriving there was a unique experience, with a certain awe touching almost every part of the day, backed up initially at least, with some powerful messaging from them. It took 6 weeks for the image to start fading significantly. I could no longer avoid the daily, sometimes hourly dissonances between what I had hoped, and the reality of what I encountered there.

Church too has an aspirational drive for me, not for importance, or leadership in the early days, but for a glorious heaven-on-earth home of love, care and belonging, of mattering to someone for example, of being wanted at least and embraced for what one brought or contributed perhaps.

In the mind, what the church could be and unfortunately isn’t, forms a drive, a striving to locate the place that possibly might be. New churches are tried and initially show promise. New movements seem to have good potential, like Willow Creek or New Wine or whatever.

Like Marjorie, in a previous thread, an exit occurs either quickly or over many years later after striving and failing to counter the dissonances of reality failing to match the dream. At all.

The loss is an enormous one. The church-in-the-mind was everything, well almost. It’s disintegrated wreckage is usually invisible to others but all too real to the former owner. Like crumbled twin towers, the rebuild is slow and painful. Living without that place is the new reality.

Fantastic comment Steve. I’d never considered church-in-the-mind or organisation-in-the-mind before and it makes a lot of sense. I’ve had to face up to person-in-the-mind as I have a strong tendency to put people on pedestals, but never thought to extend it wider.

Thanks, we were looking at this the other day, see:

http://survivingchurch.org/2022/07/19/respair-not-despair/

4th comment down after Martyn’s article

Thanks. It resonated with me when I first came across it.

The bishops have all met together in an annual trigger-fest to outsiders, known, I believe, as the “Lambeth conference”. You instinctively realise that nothing is going to change.

The basic assumption operating appears to be “One-ness” with them all wearing the same gear. How many other work groups meet wearing their uniforms at a conference? Do nurses? Do doctors? The point seems to be for our “benefit”. Doubtless up close there are hierarchical differences, but I can’t be bothered to look.

Every year they upset the same people, almost as if they aren’t able to learn. If I believe my bible, they are eventually to be punished very severely, but that doesn’t help anyone now. It’s tempting not to waste too much time thinking about them because on the whole it’s an ineffectual display. As long as this charade continues, again don’t hold your breath for any change.

The Lambeth Conference is held every ten years, not every year !

A croup of bishops dressed in costumes on my Twitter feed. Seems far too frequent whatever it is.

They only wear their robes for the photocall and eucharist in the cathedral. For the rest of the conference they wear dog collars with skirts, trousers, or whatever else is appropriate to the weather and their taste. But I agree there is something off-putting about those photos of massed identikit prelates.

Well, Steve, unusually I have to disagree with you and, to some extent, Janet on this. These are called Convocation robes. The outer scarlet chimère should, traditionally, be limited to persons holding a doctorate, but in England some of the time (including by Archbishop Welby), and usually in the Church of Ireland a more sobre plain black one is worn. The other provinces of the Anglican Communion seem to have opted for the scarlet, virtually world-wide. Given the present chaotic (and possibly schismatic) state of the Anglican Church, I see this ‘uniform’ as a kind of symbol of unity and common history: Canterbury. As Janet explains, this isn’t daily dress. It’s what you would see, e.g., at ordinations and confirmations.

I understand how these things matter a great deal to some. My own experience of robed priests included our school Anglo Catholic abuser who, unlike most other teachers wandered around all day in an academic gown even outside the school, that is when he wasn’t robed up for clerical duties. My tainted view is that the robes of whatever description, symbolise a purity or holiness not there in reality, and an authority misused at times.

Our local bishop took his off to get in the baptismal pool, and he went up greatly in my estimation as result.

Much as I try, I don’t think I’ll ever forget the associations I had in my childhood.

I did one of my curacies at a cathedral. When we were expecting a bishop or other distinguished visitor there was a form to be filled in about exactly what robes or other apparel they would be wearing, and the completed form was one of the items that would be discussed at staff meeting along with other plans for the service. At one such meeting one of the canons enquired, ‘Will the bishop be wearing his chemise?’ The men were all puzzled when the cathedral administrator and I broke into fits of giggles!

I think I’m familiar with most of the forms of clergy dress, and I can see why it would be appropriate for the bishops to wear convocation robes at the opening eucharist and other formal occasions. But for the photocall, I think it was unfortunate. Clerical collar with daywear would have been sufficient; or perhaps, cassocks and stoles made in the style appropriate to the countries represented. When people form all over the world dress identically, it looks uncomfortably like relics of colonialism. It’s a reminder that the Anglican Communion is indeed a relic of the British Empire.

Hello, Hare! Nice to see you, it’s been ages! Hope you are well.

Conversely … some years ago the churches in my then town held a well-attended ecumenical Closing Service , at my URC/Baptist church, to mark the end of the first year of our Winter Night Shelter. The Anglican Diocesan Bishop was to be the preacher.

Stewards were posted at the gate to guide his car into its designated space. They began to get itchy when he didn’t arrive. In fact he had come on foot, entered via the back door, and was happily chatting in the vestry. He was merely wearing a suit with a purple shirt and a clerical colour. There was no flummery about him at all.

Good for him!

That would be correct protocol, in my view. It would be wholly inappropriate to turn up in robes in that situation.

I should like to say to Fiona Gardner how much her excellent, truthful and honest blog is appreciated and to Stephen Parsons for instigating these blogs so we can all support each other.

In safeguarding in the Church of England without doubt, for whatever reason, some allegations are unjust and malicious. However there is no justness as to the way these are addressed. Their desperate effort to salvage their reputation from previous scandals dictates, ‘the complainant must be believed however much they change their story’ and, ‘any evidence contrary to what the complainant says is inadmissible’. This is abuse but never acknowledged as such by any Church of England organisation including those with ‘independent’ in the title. They are all tied in to follow the party line. If this blog and many of the comments are read in the light of the ‘abused’ being the falsely accused and the ‘abuser’ the false complainant, no wording, (at least, as far as I can see), would have to be changed.

For example, Fiona’s paragraph: ‘Institutional betrayal can happen through acts of commission in which the institution takes action that harms its members, for example by actively protecting an abuser. It can also betray through acts of omission, in which the organization fails to take actions that could protect members, for example taking no appropriate action and ignoring guidelines’. Indeed in the case of the wrongly accused the safeguarding groups, ‘ignoring guidelines’ is exactly what happens.

Similarly Martin Sewell’s first comment with which I would agree wholeheartedly as being our experience, possibly adding, ‘the insincerity of so called ‘Independent Reviews’ which are governed by the limits imposed by safeguarding core groups and C/E, so the truth cannot be revealed’.

It really does seem that in the Church of England nobody and no-one is accountable. Nobody cares not even after the death of Father Alan Griffin and the Coroner’s warning to the Archbishop of Canterbury that unless he responded by September 3rd 2021 there would be other such deaths. Did he respond? I have asked him twice but received no answer. Nothing that I have heard of has changed as a consequence. Perhaps I have missed it?

In response the Diocese of London commissioned Christopher Robson to carry out a ‘lessons learned review’. The terms of reference for the review, dated 3 September 2021, can be found here: https://255urd2mucke1vdd43282odd-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Terms-of-Reference-for-lessons-learned-review-FINAL.pdf.

Robson’s report, together with the diocesan response, was published on 5 July 2022:

https://www.london.anglican.org/articles/fr-alan-griffin-diocese-of-london-22-publishes-independent-report-and-response/

Thank you very much David for those links. I look forward to reading them carefully and learning more about the situation.